Exterior of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture on July 20, 2016.

Photo by Fuzheado/Creative Commons

WASHINGTON (RNS) — More than a tenth of the 1,093 religion objects at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture are Muslim artifacts.

And as the Muslim holy month of Ramadan begins, the currently closed museum is highlighting these artifacts tied to Islam on its website’s blog.

Tulani Salahu-Din, a specialist in the museum’s curatorial affairs office, featured some of the 166 Muslim objects in a blog post timed to the observance of Ramadan that began on Tuesday (April 13).

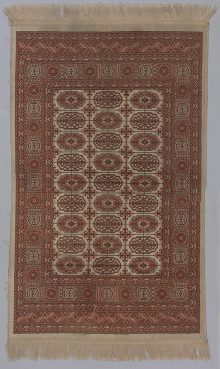

“The rituals of prayer and fasting during Ramadan, for example, have gone largely unchanged over time and place,” she writes. “Prayer rugs, dhikr beads, and kufis are the kinds of objects expressive of Muslim identity and culture; they are among the 166 Muslim objects represented in the Museum’s inaugural exhibition and national collection.”

RELATED: New Topps cards focus on Muhammad Ali’s faith

- Wooden prayer beads owned by Suliaman El-Hadi, late 20th century. Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, gift of Qaddafi El-Hadi in memory of Suliaman El-Hadi

- Prayer rug used by Imam Derrick Amin, 1970s. Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, gift of Imam Derrick Amin

Dhikr beads are prayer beads used by some Muslims during a devotional practice called “dhikr,” or “remembrance of God.”

“Such beads are distinguished by the number of beads,” Salahu-Din told Religion News Service. “They generally have 99 beads to represent the 99 names attributed to Allah. But some have 66 or 33 beads (rotated to equal 99).”

The museum’s collection includes wooden prayer beads owned by Suliaman El-Hadi, a musician who was a member of The Last Poets.

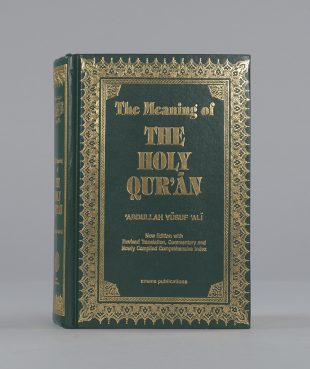

It also features “The Meaning of the Holy Qur’an,” signed by boxing legend Muhammad Ali, and a Quran acquired by Nation of Islam leader Elijah Muhammad during umrah, a pilgrimage that can be performed year-round, to Mecca in 1959.

- Handmade fez worn by Imam W.D. Mohammad, 1990s. Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture

- “The Meaning of the Holy Qur’an” signed by Muhammad Ali, 2006. Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture

“Without the material culture of African American Muslims, the Museum could not thoroughly document the African American religious experience — its diversity, its origins, or its potency in the struggle for uplift and liberation,” wrote Salahu-Din, who helped acquire the Muslim artifacts for the museum.

The museum, which has been closed due to the COVID-19 pandemic, plans to continue to expand its collection of Muslim artifacts and its Center for the Study of African American Religious Life has collected oral histories of several Muslim millennials.

RELATED: New Smithsonian museum features stories of African-American faith