(RNS) — As soon as Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey signed a bill lifting the state’s 30-year ban on teaching yoga in public schools last month, the critics began weighing in.

Christian conservatives said yoga classes might lead students to convert to Hinduism. Others suggested it was a way to sneak religion into the classroom, a violation of the First Amendment’s establishment clause.

Al Mohler, president of Southern Baptist Theological Seminary (and a 2021 candidate for the presidency of the Southern Baptist Convention), took up the issue in his blog and podcast The Briefing, voicing objections he has made many times before.

Most states do not ban yoga, and it’s up to individual school boards to determine whether they want to teach it — typically as a tool to help students move and unwind.

The practice has been used in public schools for 50 years or more. The National Center for Health Statistics, part of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, estimates 5 million U.S. children, ages 4 to 17, practiced yoga in school in 2017, the last year for which data is available.

But as Alabama shows, the practice is still controversial, especially in conservative states with large numbers of evangelicals.

Alabama legislators made sure to impose some restrictions on how yoga should be taught. Students won’t be allowed to say “namaste,” for instance. Meditation is not allowed, nor is chanting, repeating mantras or building mandalas.

Participation will be optional.

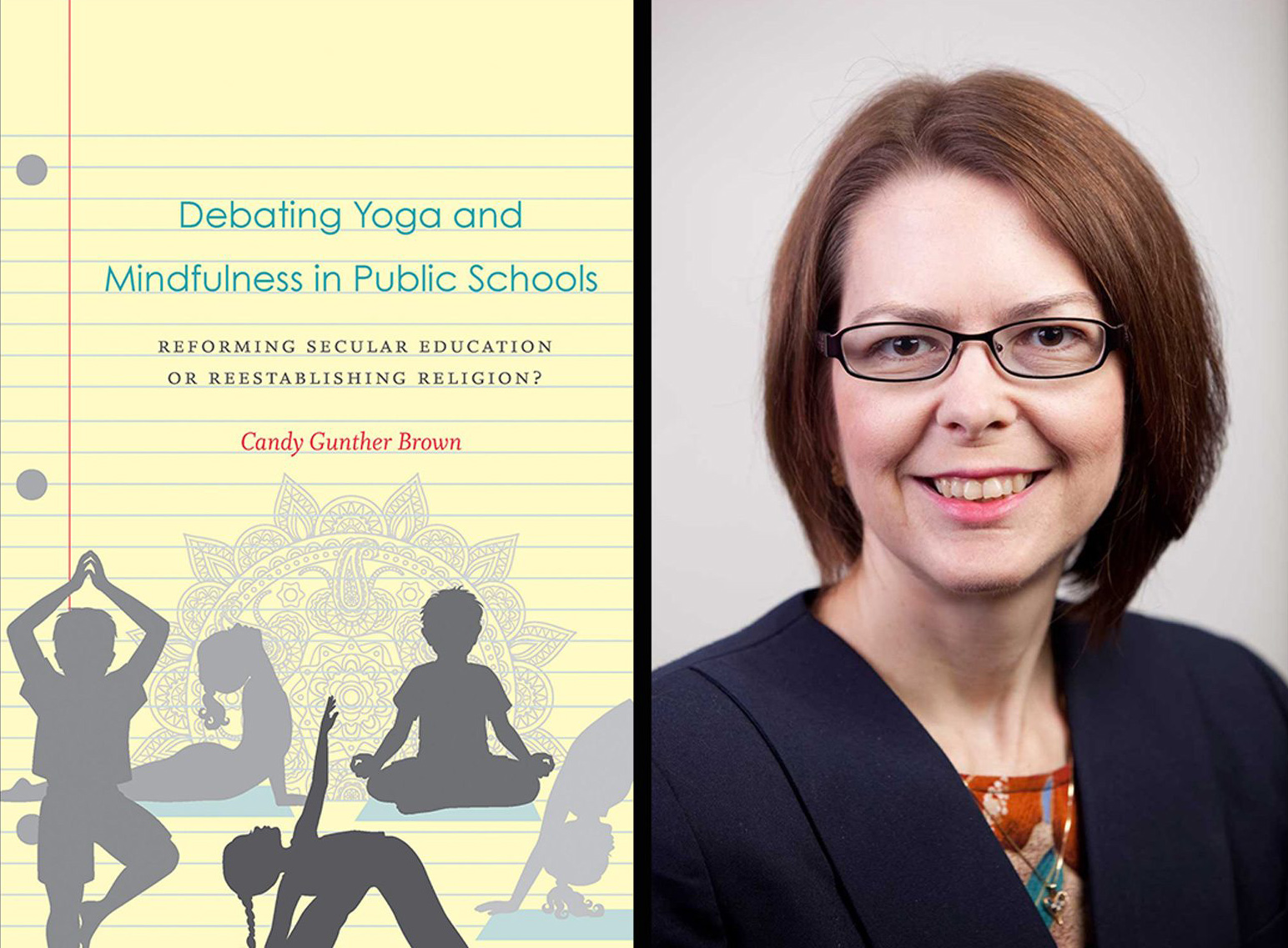

RNS asked Indiana University Professor of Religious Studies Candy Gunther Brown to help give context and advice to parents who worry about whether their child should participate in yoga. She is the author of the 2019 book: “Debating Yoga and Mindfulness in Public Schools: Reforming Secular Education or Reestablishing Religion?”

“Debating Yoga and Mindfulness in Public Schools: Reforming Secular Education or Reestablishing Religion?” and author Candy Gunther Brown. Courtesy images

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Critics say you can’t separate yoga from its Hindu roots. How do you respond to that?

The problem with that argument is it doesn’t get at how that works today. Medicine may have roots in temple worship to the Roman gods, but that doesn’t mean modern medicine has anything to do with it. To focus on the roots suggests this is a past connection. It deflects from what’s going on now — what’s going on in classrooms.

Survey research on people involved in very secularized yoga programs tend to show people who practice more frequently tend to change their religious beliefs and religious affiliation. That may have something to do with how movement affects the mind. But the ongoing question is a bigger question than its roots in the past.

Does that research on yoga practitioners changing religious beliefs apply to kids as well?

There haven’t been a lot of studies specific to kids on what the effect is going to be on their religion. Most studies involved adults.

What about the argument that teaching yoga in public schools violates the First Amendment’s establishment clause?

The question isn’t if someone is going to become Hindu or Buddhist or Jain or some other religion because they do a certain practice. Constitutionally, the question is whether there is an endorsement of religion over non-religion. If a practice is deemed to be an endorsement of religion, then that’s not constitutional. You don’t have to prove someone converts to another religion if they participate in the practice.

Has there ever been a constitutional challenge to yoga or mindfulness meditation in public schools?

Mindfulness, no. But there have been several legal cases over yoga. None of them have reached the Supreme Court. In 1979, there was a ruling on transcendental meditation that still stands as precedent, where the court found that by objective standards it’s impermissible in the public schools, even as an elective. That’s the highest federal court ruling. There was a case in California over ashtanga yoga, where the judge found yoga is religious and tied to Hinduism and Buddhism and other religious traditions, but because children would not perceive the connection, he wasn’t worried about a constitutional violation. There were a couple of rulings in Pennsylvania where the finding was that yoga in charter schools was impermissibly connected to religion.

Photo via Shutterstock.com

Alabama has an opt-out provision for students and parents. But you have said you’d be in favor of an opt-in provision. Explain why.

The language of (the Alabama) form says, in effect, ‘we understand that yoga has Hindu religious roots,’ but again, doesn’t say anything about empirical data showing people who participate in more secular forms of yoga tend to change their religious beliefs and affiliation. So the roots isn’t the point there. Even when there’s an opt-out clause, it can still be coercive because there’s a kind of peer pressure, a desire to get the favor of your teacher. Parents who haven’t done a lot of research may not know about ongoing connections to religion they might find problematic if they did more research on it.

I think there’s an affirmative obligation to provide information if you’re going to provide a program like this that would include survey results and data on the adverse effects of participating in practices like yoga and meditation. For example, it can increase anxiety and stress. There can be injuries from yoga. There are risks and benefits and there are alternatives.

The best way to constitutionally pass muster and find something that’s workable for both sides is an opt-in model of informed consent.

Why do you think schools are clamoring for yoga?

Partly it’s a fad. You want to get in on something people are doing. There are also genuine health issues in school: rates of anxiety and depression, obesity, lack of fitness. There’s a desire to shape character, deal with emotional health in a way that’s not going to put the Bible into the classroom in a way that’s constitutionally challenging. So it’s twofold: the popularity of yoga and the sense of crisis in mental health.

What would you tell Christian parents on whether their kids should participate?

The best thing is to become informed about the specifics of what’s being taught, not just on the history but the larger context. Read some articles that are well researched and thorough that give explanations of the whys. Look at alternatives that may be more appropriate for particular children. Taking the time to do the research and see if there’s a fit is good advice for anyone.

Al Mohler in his comments on yoga said he was concerned that, as a society, we are practicing syncretism, a merging of different religions. Is that inevitable?

It’s a myth that there ever was a pure religion. There’s always been an exchange of religious ideas across traditions. Yoga gets caricatured as an inherently Hindu tradition, as if there were ever a pure Hinduism or a purely Hindu yoga. There’s always been a mixture. What we have now in yoga is a mixture of gymnastics, New Thought, Christian Science with traditions that developed in the Indus Valley. On one level, there’s nothing new in terms of borrowing and remixing and repackaging.

The intensification of globalization means you’re more likely to have neighbors who have different religious beliefs and practices than your own. On the internet, you can easily access teachings and practices from the other end of the planet. In some sense, it’s to be expected that you’re going to have more mixing and matching and borrowing from global traditions. But whether that leads to higher levels of syncretism is an open question.

Some Christians who are conservative theologically may be even more convinced of the uniqueness of their beliefs and concerned to guard the purity of their beliefs and practices the more they’re in contact with other practices. So I don’t know that I’d say it’s inevitable what’s happening. But the process and borrowing and change has been going on forever.

RELATED: All-in’ Buddhist practice combines meditation and martial arts