(RNS) — It was a beautiful sunny afternoon on a verdant Ivy League campus when the “C” word was thrown at me, casually, over greasy takeout noodles.

“You are a Hindoo!!! What is your caste?” asked my chirpy, white colleague with the excitement of a contestant on “Who Wants to Be a Millionaire,” confident he was onto an easy million-dollar question. After all, since he knew about “caste,” he knew everything about my religion and me.

When I told him about my “Jati,” a cohesive social group based upon one’s occupation, tribe, village, geography, sect, lineage, etc., he refused to accept it.

“No, no, not that. The Brahma and the warrior, that thing.”

It took a few minutes to understand what he was trying to ask me was my varna — “Brahma” instead of ”Brahman” notwithstanding. Never had I ever been asked about my varna. When I did answer, he seemed a bit disappointed I was not in what he presumed were the top tiers, but we let it pass; our noodles were growing cold.

It was just one of those episodes that meant nothing to me until more than a decade later, when my own child, in the middle of a pandemic virtual social studies class on world religions, interrupted me during a busy workday to ask for our “caste.”

Though annoyed, I mentioned our Jati.

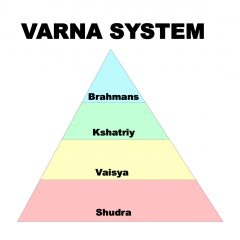

“No, no, not that. Are we Brahmans, Kshatriya, Vaisya or Shudra?”

I was taken aback again. But in the interest of time I supplied the necessary information. My child, who is typically a cheerful bundle of energy, grew ominously silent, disappointed. “I am at the bottom of the pyramid!”

My heart sank. A sense of deja vu reminded me of the earlier greasy-noodle-fueled conversation. It was the same disappointment my colleague had shown, but this was way more personal — involving my own child. Essentially, the state-mandated textbook was telling my child — nay, insisting — that because we are Hindus, we are necessarily part of a birth-based hierarchical “caste” system. And by default, that since my varna was placed at the bottom of the pyramid, we were inferior. What hurt most was that the school was teaching this in contradiction to what my own Bhagavad-Gita, my gods and goddesses, my favorite of gurus believed and practiced.

Digging a little more into school textbooks and curriculum, I found my child was not just learning about caste — being taught that “low-caste” Hindus like us were “reincarnated” as such due to our evil action in a previous life and that our potential is limited by our “place in the world” — he was also being told the defining characteristics of Hinduism were “caste system,” “polytheism” and “deities.” No mention of the profound and rich philosophy rooted in a personal quest for truth within oneself — one that influenced great Americans like R.W. Emerson, H.D. Thoreau and the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

All this despite contrary evidence throughout the history of Hindus and Hindu cosmology. The amount of falsehood and stereotyping being pushed in the name of learning left me with deep anguish and a whole lot of questions.

Why are American school textbooks, the state of California, the student councils of UC Davis and the CSU, etc., telling me because I am a Hindu of the Shudra varna, I belong to a “lower caste,” the bottom tier on some false pyramid? A non-Sanskrit word, “caste,” a vestige of the brutal colonial rule imposed on India, means nothing to me as a Hindu. Nor is that infamous pyramid something I saw in any sacred text or taught by any guru. For a second, even if I assume “caste” to be a literal translation of the word varna (which it is not), what is low about being a Shudra? And what is this nonsense about “evil action-bad karma” leading to reincarnation as a lower “caste”?

Long deemed a part of Hinduism, the varna system, sometimes referred to as “castes,” includes four different groups. RNS graphic

Hindu history is replete with Shudras who went on to accomplish greatness: authors of beloved texts and classic works like Shakuntala; rulers who halted the advance of Greece’s King Alexander into India; builders of soaring temples; saints who provided spiritual guidance to millions. They did and continue to do all this, because unlike American textbooks, and California state bodies, no one was judging them for their birth or varna. My own lived experience is contrary to being considered “low” in my socio-religious circles, just like it was contrary to the lived experience of my ancestors.

At the turn of the 20th century, a young Shudra woman who had lost her husband and all but one child to a raging smallpox epidemic migrated to the closest commercial center to start a small rice business. She did well, very well in fact. She went on to educate her child, a dark-skinned boy who carried the battle scars of pockmarks. Thank God, neither that woman nor her son had the state of California or august universities telling them they were of a “low caste” or their potential was somehow limited because of their “caste.” Thankfully, they did not read American social studies textbooks either, according to which the woman had no business running a business since she was not born in a Vaisya family. They did well and ended up being wealthy, unlike the wretched trajectory American social studies textbooks and universities would have assumed for them. The mother-son duo also ended up buying large tracts of land in and around their new hometown. We can safely assume the sellers were only bothered about being paid and not the “caste” of those purchasing their land.

Their trajectory was in defiance of the “caste” narrative peddled in the U.S. and elsewhere. Today, if that young woman were around, she probably would have laughed and dismissed the textbooks as inconsequential.

That young woman — my great-great-grandmother — would not have allowed others to define her or her sense of self. And because I inherited her spirit, I will not allow anyone to define me or misrepresent my story and heritage to my child as a “lower-caste” Hindu.

(Smitha Raj is a mother and a practicing Hindu. She lives with her family in New Jersey. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)