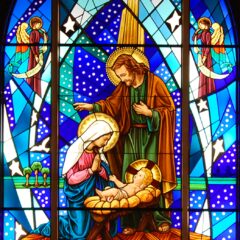

A series of stained glass windows created by artist Russell Joy depict Jesus at the Sea of Galilee, at a church in San Francisco. Photo courtesy of Russell Joy

(RNS) — From 12-foot-tall stained-glass saints to the deliberate strokes of a calligrapher’s brush, art has always been essential to religious traditions. Forbidden images, illuminated manuscripts and even maps testify to the creativity humans bring to the project of making the transcendent tangible. Artists make meaning manifest visually, tactically and aurally. These five artisans are fueled by their own faith — and sometimes that of others — to leave the world more beautiful than they found it.

- ‘In search of impossible perfection’ — Josh Berer, calligrapher

- ‘The more you know the more you want to know’ — Russell Joy, stained glass artist

- ‘Books today are boring’ — David C. Kraemer, librarian

- ‘The interior mandala is more important’ — Geishi Lobsang Kunga, Tibetan monk

- ‘Art and science became a celebration’ — Molly Burhans, cartographer and activist

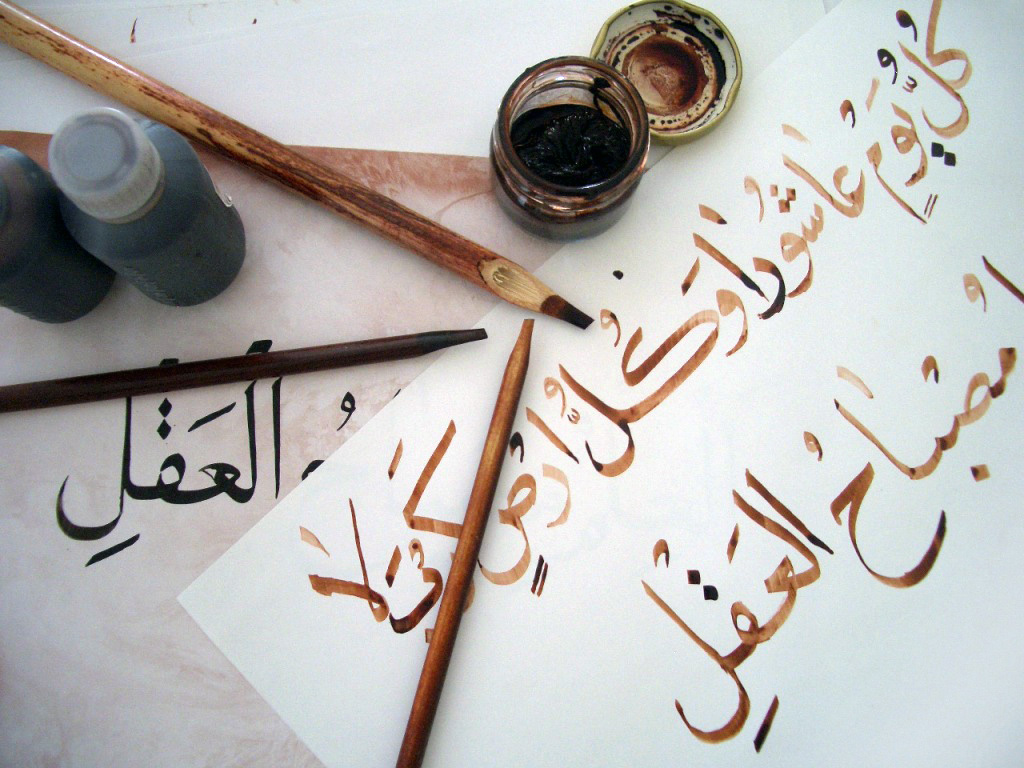

‘In search of impossible perfection’ — Josh Berer, calligrapher

Josh Berer, an Arabic calligrapher and craftsman. Photo courtesy of Berer

Josh Berer’s journey to Islamic calligraphy began with spray painting buildings as a teenager. His high school in Victoria, British Columbia, had a graffiti wall for street artists to display their craft.

“Graffiti is all about making art with the written word — just like Arabic script. Arabic just does that naturally,” said Berer.

Berer, who is Jewish, began to study Arabic when he was a student at Bard College. His Arabic studies have given him “an affinity for a civilization other than my own that contemporary media says are supposed to be enemies,” Berer said. He experimented with Arabic script in his graffiti, but he decided to pursue calligraphy in its traditional practice.

Bard College didn’t offer an Arabic major, so Berer transferred to the University of Washington in Seattle in order to pursue his degree. After he graduated in 2007, he traveled to Yemen to study Arabic, where his teacher encouraged his love of calligraphy. His teacher recommended Berer go to Istanbul to study calligraphy. Istanbul, Berer says, is the capital of Islamic calligraphy due to the community of artists who gather in the Üsküdar neighborhood, many of them to meet master calligrapher Hasan Çelebi.

“Çelebi is singlehandedly responsible for taking calligraphy from this ember in the 1970s to today,” said Berer. “For many calligraphers, the day they met Hasan Çelebi is a watershed moment in their life,” he added.

So what does a calligraphy lesson look like?

The instruments and work of a student calligrapher. Photo by Aieman Khimji/Creative Commons

Berer said it has looked the same way for hundreds of years: A novice is assigned a single line, “Lord make it easy, don’t make it difficult, Lord make it end well.” Berer said this short prayer was popular during the Ottoman Empire when the curriculum was developed. “Within this line is contained all the secrets of calligraphy,” the teacher says to the student.

The student copies that script before his lesson the next week. At their lesson, the teacher takes a brush with red ink and goes over the student’s work, correcting it.

“My first meeting with Çelebi, he didn’t even bother with the red ink and traced out the corrections with a pencil,” Berer said. Çelebi, he said, is afflicted with Parkinson’s. “His hands can’t stop shaking, but as soon as he picks up a pencil, they’re smooth and steady,” he said.

A student passes his first lesson when he can copy the sentence without needing correction. It took Berer two years to pass his first lesson.

Çelebi recommended Berer study with Mohamed Zakariya in Washington, D.C. Berer followed the recommendation and has been attending weekly lessons with Zakariya since 2012.

Josh Berer, right, observes Mohamed Zakariya at his work desk while learning Arabic calligraphy. Photo courtesy of Berer

To Berer, the community of Islamic calligraphers feels like being part of an art movement and community that has vanished in the West. “Contemporary art in the West, at least, we’ve gotten so far away from what I was originally attracted to in art — to make something that it takes a long time to learn, that there are actual rubrics of skill, of goodness and badness,” said Berer.

“The burden of beauty on you as a calligrapher,” he said, “is the physical manifestation of the divinity of the words themselves.” Berer says calligraphy is always striving toward an asymptote of perfection.

“God is divine and humans are not, so it’s impossible to reach that perfection,” said Berer. But the struggle to create something ever more beautiful and ever more perfect — and to do so within a community of artists striving for the same thing — gives Berer a sense of deep meaning. Beauty’s a burden he’s happy to bear.

‘The more you know, the more you want to know’ — Russell Joy, stained-glass artist

Stained glass artist Russell Joy poses at his studio near Kansas City, Missouri, on Friday, Aug. 20, 2021. RNS photo by Kit Doyle

Show Russell Joy some stained glass and he can instantly tell you where it’s from and who made it.

“Every studio has its own style, and it’s relatively easy to recognize. I think so, anyway,” he said.

After 40 years of making stained-glass windows and studying the art, he ought to know. Joy’s work as a stained-glass artist is part of a storied religious tradition, and he says he began to learn by studying the masters and doing repairs. Repairs are a common way to learn the craft, Joy says.

“You see what other artists have done over the years and wonder: ‘Oh my gosh, I wonder how they did that.’ And you get repair pieces in and you have to figure out, ‘OK, how did they do that?'” Joy said.

- Glass is organized by color and size at the Joy Stained Glass studio near Kansas City, Missouri, on Friday, Aug. 20, 2021. RNS photo by Kit Doyle

- Skin tones can be a very complex part of the stained glass process according to artist Russell Joy. RNS photo by Kit Doyle

- Stained glass artist Russell Joy paints a disciple’s face, by tracing from a cartoon underneath, at his studio near Kansas City, Missouri, on Friday, Aug. 20, 2021. RNS photo by Kit Doyle

- Pieces of glass sit next to a miniature of the eventual window at the Joy Stained Glass studio near Kansas City, Missouri, on Friday, Aug. 20, 2021. RNS photo by Kit Doyle

Joy began working in Ohio, tinkering with stained glass on his own until he finally started an apprenticeship at Pittsburgh Stained Glass Studios for three or four years, he said.

After six years in New York City at Rambusch Studios, he moved to his current spot in Kansas City.

He has built a solid portfolio of clients now, so Joy said he hasn’t had to take on restoration or repair work in a while. His business has stayed steady except for the recession of 2008-2009, when he said that he had to let go of four full-time workers and a part-time worker. “The phone didn’t ring for a year,” Joy said.

Stained glass artist Russell Joy glazes a window, inserting lead between pieces of glass, at his studio near Kansas City, Missouri, on Friday, Aug. 20, 2021. RNS photo by Kit Doyle

But since then, business has been booming. At least half of his business, he said, is for churches. Joy’s favorite style is delicately painted German stained glass, like from the famed Mayer studio in Munich.

Unlike oil painting, painting stained glass requires applying paint and then scraping it off layer by layer, paying attention to the exact moment when the amount of paint on the glass is just right. “You can get a piece of glass to be really soft and beautiful — that’s when the window comes to life,” Joy said. He described that delicate moment as a spiritual experience.

- Isaiah’s Commission in a Lutheran Church near Kansas City. Photo courtesy of Russell Joy

- Holy Nativity in Panama City, Panama. Photo courtesy of Russell Joy

For Joy, the best part is, well, the joy. He loves watching people’s faces when they see the light come through newly installed stained-glass windows. He says the window will bring tears to viewers’ eyes or prompt exuberant grins.

Although he has been practicing the craft for more than four decades, Joy is far from exhausting its riches.

“The more you know the more you want to know,” he said.

‘Books today are boring’— David C. Kraemer, librarian.

Librarian David C. Kraemer. Photo courtesy of Jewish Theological Seminary

David Kraemer found himself a student again when he became head librarian at Manhattan’s Jewish Theological Seminary.

“Text scholars tend to focus on texts independent of the object in which it is found,” he said. But taking over the seminary’s library with its dazzling collection of Jewish liturgical texts, manuscripts and illuminated volumes, Kraemer, a professor of the Talmud and rabbinics, said he has found himself learning from the object itself — the physical text and the illustrations and embellishments alongside it.

“There’s a lot to learn in the margins,” he said.

Although Judaism has a commandment against graven images, Kraemer says it’s a misconception to think this dampened Jewish creativity. “One of the most important areas of religious practice is transgression,” he said with a wry laugh. Jewish people around the world have never stopped making art that, to some practitioners, would definitely transgress a certain interpretation of that commandment, he said.

Graphic designs on the walls of the remodeled library feature art and images inspired by illuminations found in books and manuscripts in the collection. RNS photo by Renée Roden

Although Jewish art has survived from late antiquity in architecture, painting and material crafts, Kraemer believes books are a particularly special form of preserved art. “What survived of Jewish culture after late antiquity, more than anything else, is books,” he said.

The rare-books collection at the seminary has more than 30,000 printed books, 11,000 manuscripts and 43,000 fragments. Their collection includes an illuminated mahzor, or prayer book, from the 15th century, previously owned by the Rothschilds; lavishly decorated scrolls that tell the story of Esther; and 600 wedding contracts or ketubah.

The seminary has been undergoing a large remodeling project since 2015. In the redesign, the seminary has highlighted pieces of its rare-books collection on the walls of the large communal space of the atrium, bringing them out of the collections and into the public space.

Librarian David Kraemer, right, shows manuscripts to students in 2017, when a number of rare materials were stored at the Metropolitan Museum of Art during construction of the new Jewish Theological Seminary library in New York. Photo by Jason Shaltz, courtesy of the Jewish Theological Seminary

And, crucially, Kraemer points out that the library is one of the first rooms greeting students as they walk through the seminary’s front doors. “This is a way of emphasizing the centrality of the library,” he said.

Kraemer said his favorite piece in the collection changes by the hour. But he is in awe of micrographic illustrations — tiny Hebrew letters and words painted to form flora or fauna for manuscript decorations.

As he peruses even mundane fragments of daily record-keeping or letters preserved from the first century, the sense of holiness strikes him. “They seemed to have felt that just the Hebrew language itself, the letters, were holy,” Kraemer said.

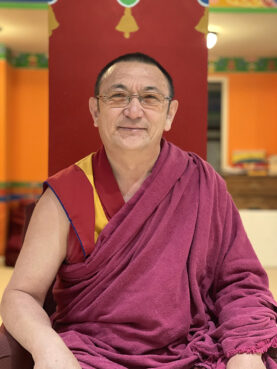

‘The interior mandala is more important’ — Geshe Lobsang Kunga, Tibetan monk

Monks of the Tibetan Mongolian Buddhist Cultural Center in Bloomington, Indiana, work on a mandala in 2013. Coutesy photo

The creation of mandalas is a rite of tantric initiation in Tibetan Buddhism. A mandala is a cosmic diagram that represents the celestial palace of a deity. Mandalas are most often made of sand but can be made out of a variety of materials, including grains of rice, cloth or larger 3D structures of wood and copper.

Geshe Lobsang Kunga. Courtesy photo

Geshe Lobsang Kunga, director of the Tibetan Mongolian Buddhist Cultural Center in Bloomington, Indiana, has been a Tibetan monk for more than 40 years. Over that time, Kunga has constructed many mandalas. For Tibetan Buddhist monks, Kunga says, the mandala is primarily an experience of meditation and focus.

Kunga was born in Tibet in 1964 and entered the monastery in 1980. After 17 years of studying the six perfections of Buddhism, he left for a monastery in South India for deeper study of tantric meditation.

Kunga calls a mandala a blueprint — and there are many different “home” designs. “The mandala is the celestial palace of the Buddha, so it depends on the individual design you undertake,” he said.

A senior monk who has practiced the mandala design to perfection will guide the process of assembling the mandala. Kunga says it can take a team of six to eight monks around a week to make a sand mandala.

While pouring and shaping the brightly colored sand with small funnels and scrapers, the monks wear masks so as not to blow away the sand by talking, sneezing or coughing. The first monk begins by shaping the center of the mandala. Slowly, the team of monks applies the colored sand outward from the center.

The sand used by Buddhist monks to create a mandala. RNS photo by Sally Morrow

The designs are meant to be three-dimensional, said Kunga, even the flat sand mandalas. They are a blueprint, he says, intricately mapping out a home for a god. They have four doors to represent the four directions of the wind and often include patterns that indicate divine attributes. After they are finally completed, these painstakingly created are destroyed.

The monks meditate as they create the mandala, they pray around it for its brief life period, then they will slowly dismantle the mandala by sweeping it away. The destruction of the sand mandala emphasizes a mandala is not so much about the exterior product as it is about the interior design, says Kunga. “It is more important to have the structure, the detail and the image of the mandala in your mind during the visualizations,” he said. The true celestial palace is accessed through the meditation of each monk who participates in the mandala’s creation.

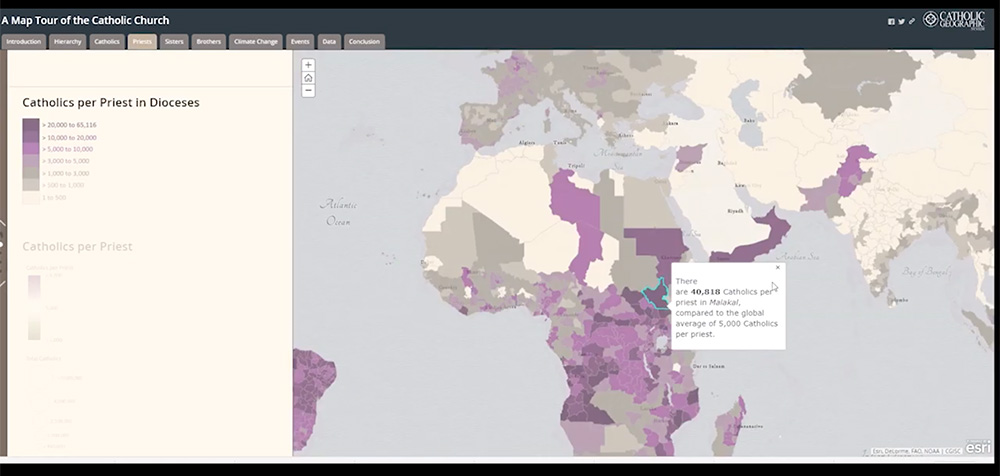

‘Art and science became a celebration’ — Molly Burhans, cartographer and activist

Cartographer Molly Burhans. Photo courtesy of Ashoka

Speaking from her New Haven home in a purple blazer and gray T-shirt, Molly Burhans infuses creativity into her more-than-full-time job as the executive director of GoodLands. GoodLands uses contemporary digital mapping techniques to help Catholic parishes, universities and monasteries survey their property and manage their land. Burhan’s digital cartography startup has won her wide recognition — from the United Nations to the Vatican.

Running GoodLands, she admits, means most of her time now is spent administratively rather than creatively. However, “every product we create has to be beautiful,” she insists.

“Beauty is a part of everything we do,” she said — even for something that could be just an Excel sheet. “I actually built a custom piece of software that integrates the liturgical calendar in an overlay on our budget.”

Burhans included the full Catholic liturgical calendar in this overlay — not just the cycle of Catholic seasons of Lent or Christmas — but every feast day of every single saint—even obscure ones.

“Maybe someday I’ll get sleep,” she said.

Burhans has always loved to map stories visually. She and her sibling would make 200-slide PowerPoint presentations of various tales. A favorite was about a cast of characters called the Breakfast Bunch, a crime-fighting crew of comestibles.

“Solving crimes before lunch. Breakfast bunch, breakfast bunch, detective toast, got a hunch. Where is bacon? I don’t know,” sings Burhans to the tune of the Spider-Man theme song.

An example of the digital cartography created by GoodLands. Courtesy image

Burhans was 14 when her father invited his SIMS-loving, fort-building daughter to design a visual for his research on yeast-cell death. From there, Burhans developed a side hustle of doing science illustrations and data visualizations while pursuing ballet and choreographing modern dance.

“Choreography is a totally immersive art. The human body is an instrument in the landscape of space — or many bodies, together, in kind of a communion,” she said. She related this to her current love of cartography. Burhans took what she described as a “meandering” path through college. She described herself as agnostic at the time, but she began to yearn, as she said, to “fill the infinite” inside her.

Science led her to her faith. She began to map out the systems of the body and was in awe of its molecular and cellular design. “If I couldn’t love the soul, I could at least love this masterpiece,” she said.

During her senior year of college, she had what she calls a 20-minute conversion moment. She found herself confronted with the truth that the meaning of life was love. She went to a doctor to see what was wrong with her. And then she went to a Jesuit to try to sort out what exactly the question was to which love was the answer.

Burhans was baptized Catholic and eventually — after taking advanced philosophy classes and briefly considering religious life as a sister — was confirmed as a Catholic.

“Art changed, and science changed for me — they took a turn as celebration,” she said. And her cartography work is, ultimately, a celebration.

The Catholic doctrine of the Eucharist, she says, is essential to her work.

“Maps are powerful tools,” Burhans said. Spice traders killed each other for maps in the Renaissance. But Burhans sees them as opening up different riches: for unlocking the land’s potential.

She sees this as echoing a Catholic understanding of the “Eucharistic potential of the world,” that everything can become a celebration of creation and of life’s ultimate meaning: love. In her case, maps, beautifully and carefully designed, can choreograph human interaction with the world and unlock the potential of what faith has and what faith can create.