(RNS) — I first came to know John Shelby Spong the way many young, progressive clergy did: through his writings. I was only three years out of seminary, serving a very rural congregation in a very conservative part of the country, when I read him for the first time. His book, “Rescuing the Bible From Fundamentalism,” was recommended to me by a friend.

It transformed me entirely.

A little personal context might be in order. I grew up Catholic. At a very young age I was persuaded that my call was to the priesthood. I spent eight years in the Catholic seminary with every hope and intention of being ordained. The idea of it enthralled me.

What didn’t enthrall me was an adherence to theologies I could not reconcile with my personal thoughts and feelings about the faith. I kept asking for explanations about the Virgin Birth that made sense; about a closed Communion table; about the ordination of women; about the teaching there was no salvation outside the church — a teaching that seemed to place limits on a God whose love we also described as unconditional.

Time and again, the response went something like this: John, these are the teachings of the church and have been so for 2,000 years. Who are you to question them?

After seven years, with the time of ordination fast approaching, the reconciliation I was hoping for between my evolving faith and the teachings of the church still hadn’t occurred. When I finished my eighth year, I left. Not out of anger, or even thinking the church was wrong. It was just a painful realization that I could not take the ordination vow that would bind me to obedience to doctrines — and to teaching doctrines — I did not myself believe.

RELATED: Bishop John Shelby Spong, firebrand who championed LGBTQ inclusion, has died

Eventually my journey to ordination was revived through another pathway, and it was another eight years before I picked up that book by Bishop Spong.

Here was a scholar, a man of deep intellect. As a bishop, he was also a role model that, given all my years being raised by parents who taught me to respect authority, I knew I had every right and reason to trust. And he was putting down into words answers to the questions I had been asking all my life.

I can’t begin to describe either the validation that I finally found and needed, nor the inner peace that came to me.

From that time on, he became a hero to me.

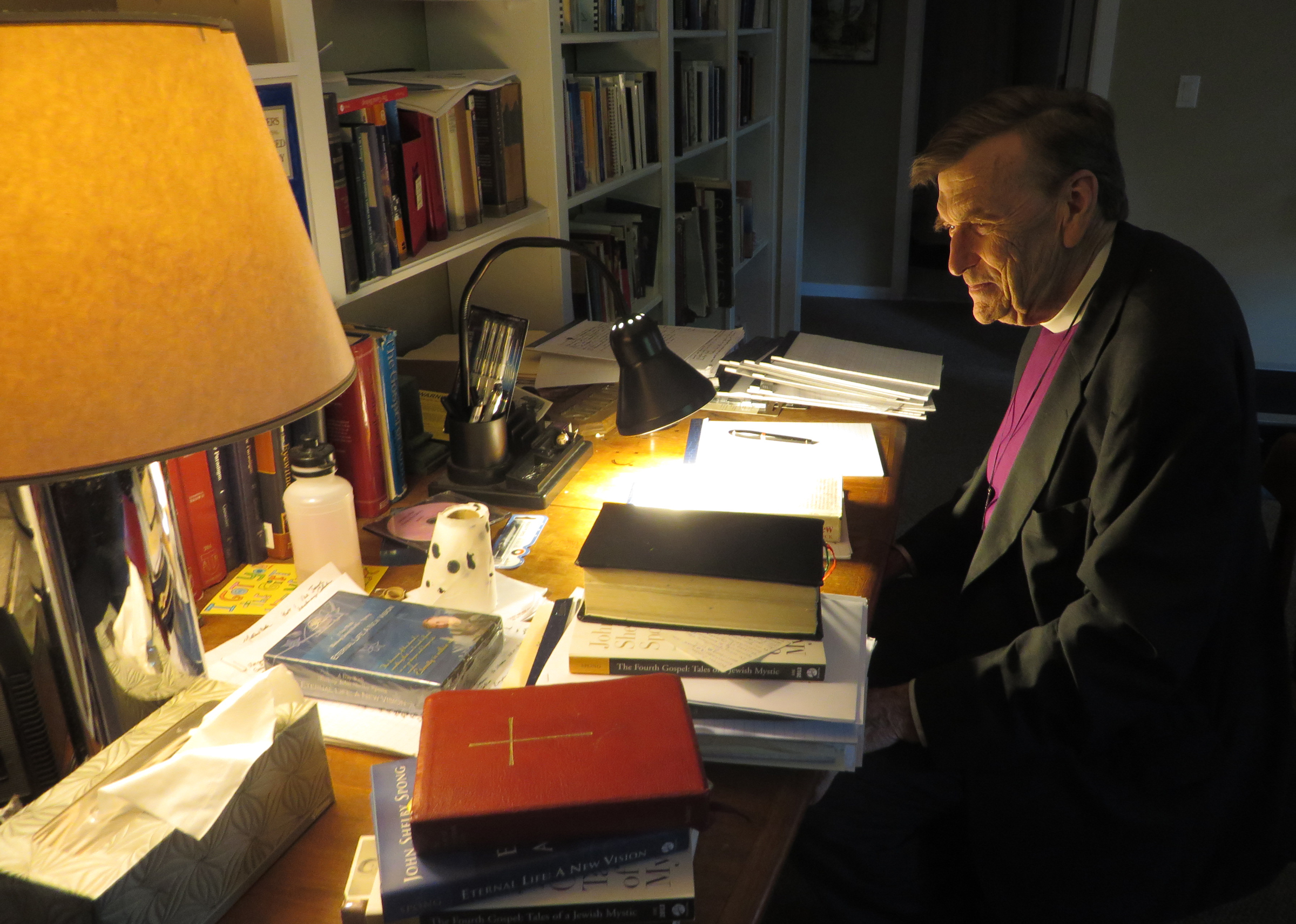

John Shelby Spong sits at his desk at his New Jersey home on Sept. 12, 2013. The liberal churchman wrote longhand with a fountain pen on yellow legal pads. RNS photo by David Gibson

Over the next couple decades I would await with great and joyful anticipation Spong’s next book. Each one asked a question I was interested in. Each gave language and vocabulary to what my inner faith-workings had been grasping for over many long years. Each book expanded my theological horizons. They didn’t just validate theological assumptions I was called rebellious for hanging on to, they expanded them in ways my own imagination had not yet been given permission to explore.

I needed that validation in order to pursue my theological calling — not just with vigor and passion, but without shame and doubt. Spong rekindled within me the pursuit of a theology without limit or bound. Every question was in play.

But he also modeled a rigor and a discipline. His was no “do what you want and think what you will and it will all be permitted and blessed” kind of theology. His research was thorough and impeccable. His references were deep and sometimes arcane (but never irrelevant) — the kind of sourcing that could only occur through long years of intellectual pursuit and more than passing curiosity.

As rigorous and well-referenced as his sources were, his writing style was deliberately accessible — unlike other tomes I’ve used to expand my horizons. His were writings I could confidently share with my congregations. They, too, would grow to love him. They, too, were able to validate questions they had long wondered about but were often too timid to explore. My greatest joy came in the open discussions with the lay folk I was called to serve, who suddenly found the wisdom of the sages available to them.

I did not meet John until very late in his life.

By that time, I had been elected the general minister and president of the United Church of Christ. I had written a couple of books myself. I had completed my doctoral work and dissertation on “White Privilege and Its Effects on the Church.” I became a leader who would sometimes get invitations to speak to various audiences.

On one such occasion, I arrived and found a banner outside the auditorium. The speaker preceding me was none other than Spong. I went in and found a seat next to his wife. She recognized me from the photo on the display. John was his usual magnificent self. When after his presentation he came and sat with me and my wife, I found him to be as gregarious and affable, as open to conversation with a stranger as you would ever want or hope a person to be.

That moment also validated something for me. I won’t dare to call myself his peer — he had few of those. But I did come to call him a friend, and a mentor. My time with him was brief. He was already suffering a great deal by the time I met him.

To his dying day he remained one whose light shone in many corridors. His kind and compassionate spirit uplifted many hearts. He spoke his words without apology — always inviting the church to grow beyond its current assumptions about its capacity to do so. He was responsible only to the truth he came to know in the God and Jesus whom he worshipped.

We are all changed because of him, and the influence and impact he created is far from having run its course.

(The Rev. John C. Dorhauer is general minister and president of the United Church of Christ. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)