(RNS) — Balbir Singh Sodhi was working at his Arizona gas station in 2001, four days after Sept. 11, when he became one of the first victims of skewed attempts at retribution for the attacks. A Sikh, Sodhi was mistaken for an Arab Muslim by a man who had declared he was “going to go out and shoot some towel-heads.”

Sikhs have been commonly mistaken for Muslims because of their turbans and often experience anti-Muslim discrimination.

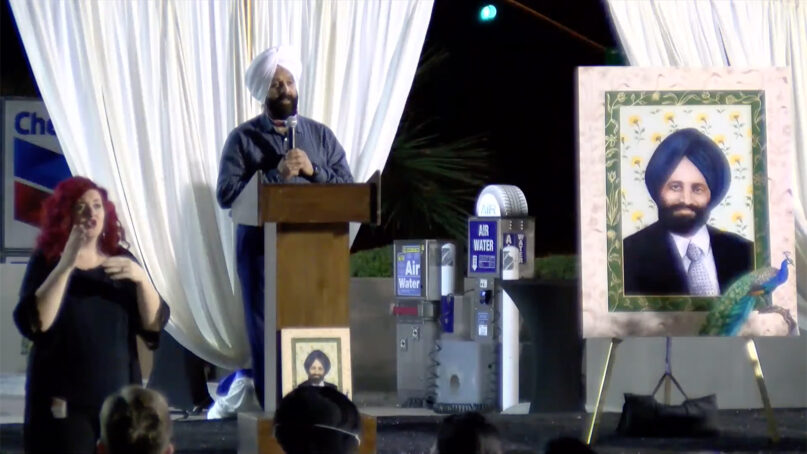

On Wednesday (Sept. 15), members of Sodhi’s family, friends as well as nationally known elected leaders and people of different faiths gathered at the Chevron station in Mesa to memorialize Sodhi.

Catholic Sister Simone Campbell revered Sodhi as a saint and a holy man “for his generosity in caring for neighbors.”

Imam Khalid Latif, who was a New York University student when 9/11 happened, expressed his gratitude for the Sikh community because, amid the rise in hate and racism, “I’ve never heard once any of my Sikh brothers and sisters (say) that we will separate ourselves from people who are Muslim.”

The Rev. Larry Fultz, of the Arizona Interfaith Movement said Sodhi’s death ignited a “better understanding of the Sikh faith” and helped him recognize that “when one faith is attacked, all of our faiths are at risk.”

RELATED: An animated film to chronicle life of ’Sikh Captain America’ in aftermath of 9/11

Sodhi’s younger brother, Rana Singh Sodhi, who has acted as a family spokesperson and helps educate others about the Sikh faith and identity, told Religion News Service that the gathering reflected “the basic teaching from Sikhism.”

“All the different people, different genders, color, creed — we all are a human first,” he said. “We respect and understand and love each other.”

In this Aug. 19, 2016, file photo, Rana Singh Sodhi kneels near his service station in Mesa, Arizona, next to a memorial for his brother, Balbir Singh Sodhi, who was murdered in the days after the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks. (AP Photo/Ross D. Franklin, File)

U.S. Rep. Greg Stanton of Phoenix, Mesa Mayor John Giles and Erika Moritsugu, President Joe Biden’s liaison to Asian Americans, were also present to honor Balbir Singh Sodhi. The event was hosted by the Sodhi family and the Sikh Coalition, in association with the Global Sikh Alliance.

Sodhi died one day before he got the chance to speak at a news conference he helped organize “to educate more people about our turban and about our beard,” his brother said. The elder Sodhi feared that someone in their community might get hurt and he had a “feeling of ‘we better do something,’” said Rana Singh Sodhi.

“My brother wanted to save somebody,” he said, “and I will keep his word.

“I’m going to do it my whole life. I’m not going to stop.”

RELATED: Anti-Sikh bigotry didn’t start with 9/11. That fact got me through it.

Sodhi, remembered by many as “Balbir Uncle,” grew up in Punjab, in northern India, and was the third of 11 siblings. He left India for the United States after the 1984 anti-Sikh bloodshed. Before opening his gas station, he earned money, much of which he sent home to India, by driving cabs and working the register at 7-Eleven.

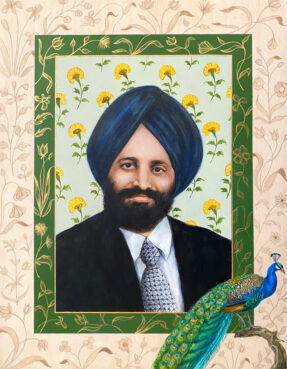

A portrait painted of Balbir Singh Sodhi. Courtesy image

He felt relief, excitement and gratitude in America, a nation where “he can practice his faith freely … where his family will be safe,” said civil rights leader and filmmaker Valarie Kaur at the gathering.

Sodhi was known to give away candy to the children of customers, who called him “Mr. Bill.” He would allow youth to ride their skateboards outside his store, and he’d let people down on their luck fill up for free.

Kaur, who is a friend of the Sodhi family, quoted Sodhi as saying, “God wants us to serve all.”

Soon after the twin towers in New York City fell, Sikhs in the Mesa community began calling Sodhi and his brothers, alerting them that they were being harassed. They planned the news conference “to tell the nation that we were Americans who were hurting just like them,” Kaur said.

On Sept. 15, 2001, Sodhi went to Costco to buy crates of flowers to plant in front of his gas station. There, he saw a jar at the checkout for donations for 9/11 victims, which he emptied his wallet into, Kaur said. He also called his brother and told him Costco was out of American flags, which he wanted to place outside of his store.

As he was planting flowers, shots rang out. He fell and “bled to death not knowing who shot him or why,” Kaur said.

“Balbir Uncle’s story could have ended here, as so many stories do when one dies, but this was not the end of his story,” Kaur said. “His death was a beginning because of how he lived.”

Kaur referred to the gas station as the “second Ground Zero.”

“It is the Ground Zero for all the people who have been killed or harmed in the hate violence, the state violence and the wars abroad for the last two decades,” she said.

Sodhi, Kaur said, “lived a life of love.”

“Balbir Uncle’s life was our North Star,” she said.