(RNS) — When the Rev. Steven Charleston finally gave in to his friends’ encouragement and created a Facebook account a decade ago, he didn’t know what to post.

Charleston didn’t have a cat, so the cat photos that litter social media were out. Neither did he have recipes or political opinions he particularly wanted to be known for.

So the Choctaw elder and former Episcopal bishop of Alaska started writing down “the first thing that came into my mind after I’ve been praying in the morning,” he said.

Today, those daily meditations reach thousands of followers on the social media platform — a community he said includes people of all cultures and races, all faiths and no faith.

The success of his posts, Charleston said, is “not because of me.”

“From the very beginning, it was clear to me that there was something else happening here by writing these things down. There was another author at work,” he said.

RELATED: First Nations Version translates the New Testament for Native American readers

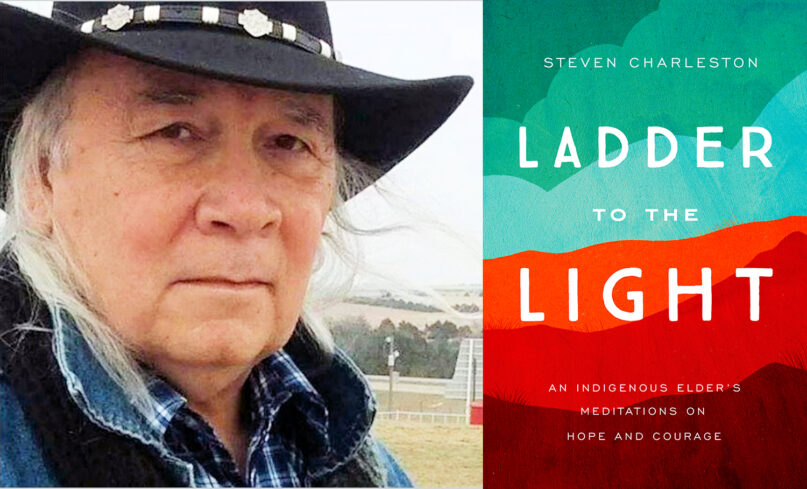

Earlier this year, Charleston published some of his meditations, along with commentary, in a book called “Ladder to the Light: An Indigenous Elder’s Meditations on Hope and Courage” that he describes as a director’s cut of his Facebook presence.

As his timeline has grown darker, filled with protests and the pandemic and growing distrust in institutions, the image of the kiva has come to mind, he said. The kiva is a sacred space for some Native American nations in the Southwest, an underground chamber reached by ladder that invites people not to escape the world, but to enter into it.

He hopes “Ladder to the Light” will carry that vision beyond Facebook.

“It’s against all of that darkness, all of that fear and anger, that my little book is coming along, holding up a light, saying, ‘There’s a way to the light for all of us. We don’t need to be like this. There’s a different path we can follow, and it’s one for everyone,’” he said.

Charleston talked to Religion News Service about “Ladder to the Light” and what Native America has to teach others about climbing out of darkness. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

You write in the book that we are living in “a time of darkness” and that “Native America knows something about resisting darkness. It is what we have been doing for more than five hundred years.” Can you explain that?

It is a time when people feel we’re living in an apocalypse. Things are collapsing. Things are getting chaotic. Things aren’t working like they used to. We don’t trust the scientists. We don’t trust the educators. We don’t trust the politicians. There’s nobody left. You can’t trust people of different nations or different colors or different religions.

And yet, when I hold up “Ladder to the Light” as a beacon of hope, how can people trust that? Part of the answer is Native America has already lived through an apocalypse. That’s what happened to us. It’s apocalyptic to suddenly have strangers show up and order you off your land and force you either to be exterminated or to move into these kind of death camp areas where you were held as prisoners. It’s apocalyptic to have your children taken away from you and forced into schools where they were made not to speak your language.

We have survived loss of language, loss of culture, loss of land, loss of religion. But we didn’t go extinct, and we didn’t die, and the reason we didn’t is because of the core faith and vision that Native America embodies. The depth of what we had committed our lives to was so strong that it allowed us to survive the apocalypse.

I believe our message to the larger society today is we have learned something. We know something. And it’s not just for us. It’s not a little ark, just for us alone, to ride out the storm. It is a broad path that we can offer — the ascent of the ladder from the kiva. It is the way for us practically, spiritually speaking to go step by step from darkness to light.

Is darkness always a bad thing?

Darkness is not intrinsically bad. In fact, it can be healing and comforting. The darkness of the kiva is a womb in Mother Earth, for it is where we all emerged as human beings. My people speak of this, too, along with people like the Hopi and Pueblo peoples — that the origin of humanity was within the womb of the earth, and we emerged just like babies would from the earth. We came out from the mother and made our life here in the light, but in the kiva is this nurturing, protective, enclosed feeling of being embraced by life. It envelops you like a womb and it feeds you and helps you until you’re strong enough to make the ascent back to the light to continue doing what you’ve been called to do.

There’s no dichotomy here like there is in Western thought between light and dark, which is an equivalence of light, good, and dark, bad. Both are needed. All things must be in balance in the Native tradition. So the darkness plays its role, both as a nurturing element for us and a place of our origins. And the light plays its role as a destination for us, a focal point for our transition. So they work together in a symmetry, in a constant equilibrium that just keeps everything in balance. The key word for our future is we must learn to live in balance.

RELATED: Think we’re living through the Apocalypse? So did first-century Christians (COMMENTARY)

Why is faith the first rung of the ladder needed to climb out of darkness?

Because you’re not going to be able, on your own, to think your way out of it. We have had a long history in the West of believing we could somehow think our way out of this. If you think you’re going to come up with technology to solve every problem, you’re kidding yourself, because ultimately what makes a society work is its spiritual values.

When Europeans first came to our homeland, we had an opportunity as human beings to take a vast step forward, because two clans of the tribe had met. There was a clan of tool makers, and there was a clan of community builders. Community builders — my people — didn’t have all the tools, all the technology the Europeans had invented, but we knew how to live in stable, whole, kind, compassionate societies — communities where women were respected, where our children were safe, where everyone had enough to eat.

And so when our community builders met the tool makers — the technological people — we had a great opportunity to combine our abilities, because Europeans had real problems with community. They had child labor, they had slavery, they had the lower classes, they had people living in squalor while a few people lived in mansions. They were in desperate need of finding a more just and humane way to create a civilization. And if the two had cooperated, we would be far ahead of where we are now. There’s still time.

The one thing Native people know is that, at the end of the day, everything we see around us is a spiritual reality. If you can embrace that thought that there must be something out there that has some greater power in our lives than we were able to create for ourselves, in that humility is our first step towards healing.

Another rung you mention is action. What are some practical steps people can take if they’re feeling afraid and hopeless looking at everything going on in the world?

Like I said, faith is the first rung, and religion can be a very positive motivator — any faith tradition that teaches compassion and kindness and mercy. That impulse to do something to help others, to act out of a motivation other than selfish desire, but instead toward the healing or helping of other people, that’s within all of our faith traditions, but it’s wasted if those faith traditions keep maintaining an exclusionary attitude toward one another.

So one of the first actions is the action of tolerance, of openheartedness and of open-mindedness. We’re living in a world now, particularly in this country, where we’re being told daily who we’re not supposed to like and trust and who the enemy is. People of faith can counter that argument by saying there’s plenty of people we can trust and embrace, and they come in all colors and all sizes and all shapes, and we all need one another because we’re all in the same boat.

RELATED: Churches return land to Indigenous groups as part of #LandBack movement