(RNS) — Wajahat Ali begins his memoir of growing up in Fremont, California, with a list of the kinds of Islamophobic hate mail he has received over the years.

“Go back to where you came from,” also the title of his memoir, is one of the most ubiquitous of the epithets Ali, the son of Pakistani immigrant parents, was subjected to — and also the most polite. Others are too profane to be quoted here.

The commentator, writer and playwright has become a familiar presence on political talk shows and on social media, where he has nearly 280,000 Twitter followers.

His new book, his first, tells of his upbringing in an immigrant community — he spoke only Urdu until the age of 5 — emerging as a kind of spokesperson for other Muslim students at the University of California Berkeley after the 9/11 attacks.

Ali writes with plenty of righteous anger at the ways the people of his community have been ostracized: religious and racial discrimination, the moderate Muslim trope, white supremacists and systemic racism.

RELATED: Religious communities have a moral obligation to make the internet better

But Ali’s story is also personal, heart wrenching and raw and it includes lots of painful episodes. Soon after 9/11, his parents, who sold academic software, were arrested and imprisoned for mail fraud, wire fraud and other counts as part of a large Microsoft anti-piracy criminal indictment. They spent nearly five years in prison.

More recently, at the age of 2, Ali’s daughter was diagnosed with stage 4 cancer and needed a liver transplant.

Throughout all these trials, (and the attendant anxiety and OCD) Ali reveals himself to be a warm, vulnerable, often hysterically funny writer with deep and abiding affection for his family, his immigrant Pakistani community and his Muslim faith.

Ali spoke to RNS by phone from his home in Virginia, where he lives with his wife, Sarah, a doctor, and his three children. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

You start by saying that being an American is both comedy and tragedy. Explain.

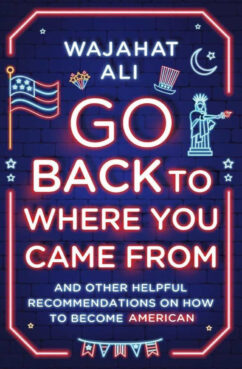

“Go Back to Where You Came From: And Other Helpful Recommendations on How To Become American” by Wajahat Ali. Courtesy image

It’s a country that during the pandemic had a food fight at the Golden Corral because they ran out of cheap steak. At the same time there are communities right now desperately trying to get a vaccine but because they’ve been marginalized for so long they don’t have access to health care. You sit there and look at the dichotomy. America is a bouillabaisse, a wonderful microcosm of the absurdity of human life and the gamut of human emotions that humans are capable of. You see it all in America.

You’re equally critical of white America as you are of the U.S. Pakistani Muslim community. How have both received the book?

I try to be an equal-opportunity offender — I dish it out to my fellow Americans, Pakistanis and Muslims. I also dish it out to jinns once in a while. So far, it’s been overwhelmingly positive. I assumed it would be, ‘Don’t air your dirty laundry.’ And then there’d be a corrective narrative — ’We’re not like that; We’re much better.’ But most people seem to appreciate that it’s raw and real. It’s lovely to see the Muslim community embrace the book. People are applauding me for being vulnerable. I don’t need medals or awards. I just told the truth. Sometimes telling the truth is a revolutionary thing.

Do you feel an outsider in both communities?

I’ve always been a bit odd. I never followed the checklist. It gives me the ability to maneuver and critique and do my own thing. It does make you an outlier. In the long run, you find it’s oddly liberating. You get comfortable in your own skin, as opposed to contorting yourself into creating this perfect caricature that’s always uncomfortable.

You have a hilarious checklist of how Muslims can be more moderate. Explain why that trope of the “moderate Muslim” is so insulting.

The assumption is that I’m not moderate. By default, we’re these savage beasts from the Middle East who are about to put a hijab on your wife and implement Shariah. It’s a double-standard that is not asked of any other religious community: We accept you only if you fulfill our version of being a sanitized, civilized Muslim.

There’s always an asterisk next to your name. It’s like TSA. Everybody else is invited to board the plane but you get double-extra security. You get the pat down and the X-ray machine and still after you pass all those extra hurdles when you walk down the airplane aisle everybody still looks at you as suspect. That’s why it’s so hurtful.

Is this the first time you’ve publicly talked about your parents going to prison?

I’ve never hidden it, and twice before, some reporters mentioned it. But I never wrote about it in depth. It was a huge chunk of my life that shaped and formed me. It’s like a puzzle and you finally put the missing piece of the puzzle in and it tells the entire story. And then people go, ‘Oh wow. That changes everything.’

Was it difficult to write about it?

The concern was less about me and more about my parents. They say memoir is a type of theft. You tell your version of the story and use other characters, but they don’t have the agency to fight back. My fear was, after they’ve gone through so much, would this story be an excuse to mock them, ridicule them and laugh at them? My parents were concerned that their story would be used to attack me.

But I wasn’t that afraid of that. I did think it would help shatter this model minority stereotype, and for so many people I was hoping it would give them permission to tell their story. What’s happened is that people say, thank you so much. It’s the same thing with mental health. I mention OCD and anxiety disorder. In our communities admitting it is a sign of weakness. You’re supposed to white-knuckle it. If you admit it, you come from a bad family.

Is humor the best way to dismantle anti-Muslim hate?

I don’t know if it’s the best way, but it’s my way. Everyone has different skills. For me, it’s using humor and blunt truths to make people more receptive to otherwise hostile ideas.

Your book is filled with lovely Quranic passages that gave you so much comfort over the years. How did you learn them?

I come from a religious family. We fasted. We prayed. I had people teach me the Quran. We had religious gatherings in my home. I think I was always disposed to spirituality. That became part of my life. When this happened to my family, I leaned heavily on that. You lean upon what you know. You lean on the faith tradition and the stories. When you go through a crisis you need something to give you hope and keep you afloat. It was like a daily affirmation that I needed sometimes in the darkest of moments.

You also relate the story of your daughter getting diagnosed with stage 4 cancer and getting a liver transplant. How is she doing?

She’s 5 years old. She’s cancer free. She’s in virtual school. She got her “Encanto” Isabella dress. She swings and twirls and dances and puts a flower in her hair. Her hair is back, her weight is back, her color is back. People need miracles, and I have a living miracle prancing around my home every day.

In your TED talk you urged Americans to have more children and you end the book saying that being a father is your greatest achievement. Did anyone push back?

The talk was actually a Trojan horse to make a point about more progressive policies pro-natal policies — paid parental leave, childcare, better wages for women. Having children is an audacious act of hope. More so than ever, we need to invest in hope. It’s not enough to say it. There has to be an intention. You need it to survive. The absence of hope is apathy and cynicism. Is that the legacy we want to give our kids?

RELATED: The unlikely story of America’s highest ranking Muslim soldier and TikTok favorite