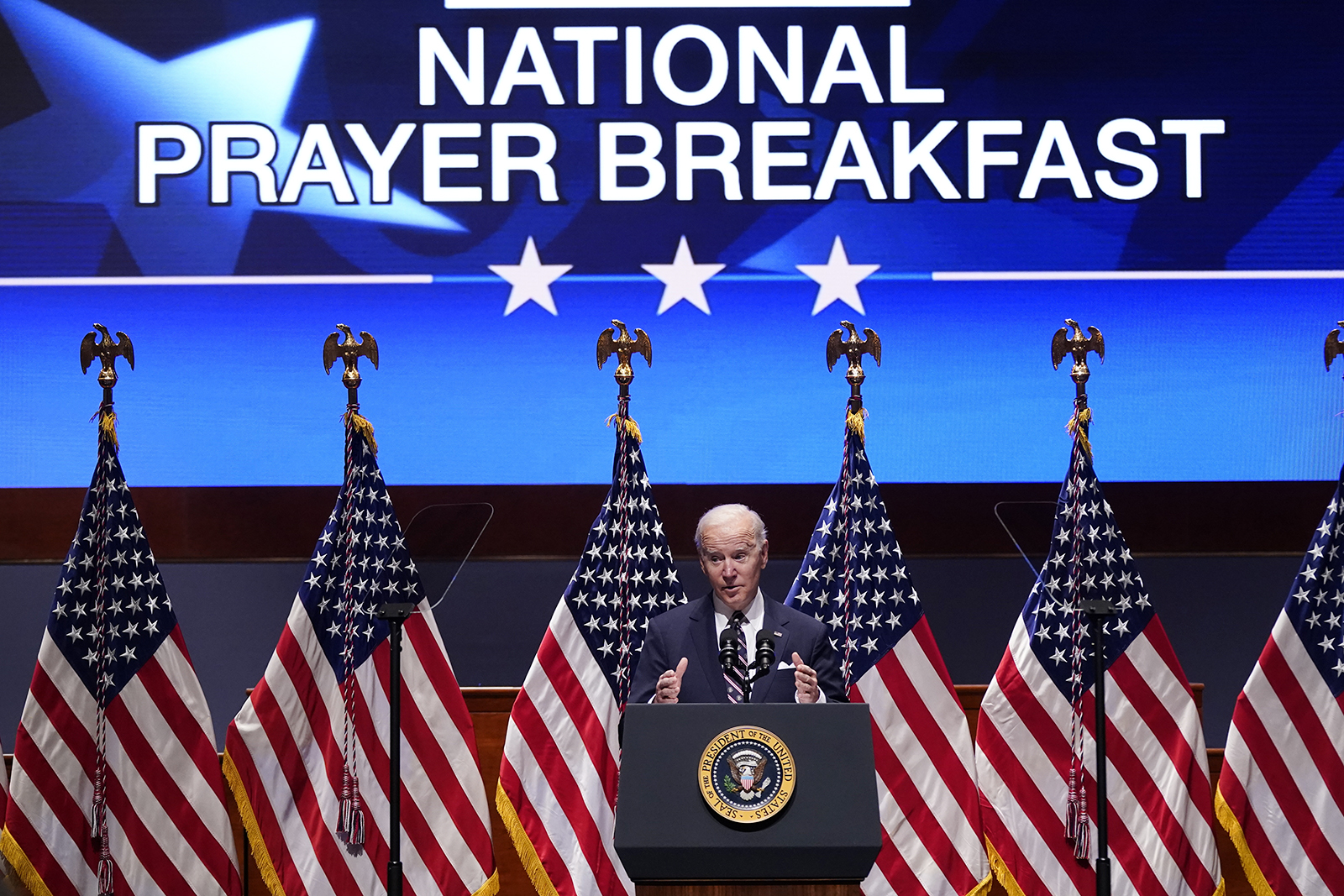

(RNS) — At this year’s 70th National Prayer Breakfast, broadcast around the world, President Joe Biden quoted his predecessor Dwight Eisenhower in extolling the power of prayer to help Americans find purpose: “President Eisenhower, the first president to attend this breakfast 70 years ago, said, ‘There’s a need we all have in these days and times for some help, which comes outside ourselves.’”

Prayers, even those seeking outside help, have traditionally come from deep inside the person praying. It starts from within, transcends religion or spirituality and is a means of communicating thoughtfully and purposefully with one’s spirit or inner consciousness.

Historians and religious leaders describe prayer as a conversation with or a statement to a higher power, and it presumes that the supplicant has faith or trust in someone or something.

That’s less and less how prayer is employed in our culture today. Last Friday (Feb. 4), World Cancer Day 2022, Dr. Mehmet Oz, a talk show host now running for U.S. Senate from Pennsylvania, sent “thoughts and prayers” to victims of the disease. Queen Elizabeth II sent “thoughts and prayers” to those in Tonga affected by the recent volcanic eruption. This trite nicety even has its own Wikipedia page.

RELATED: Some praise, some doubts as Facebook rolls out a prayer tool

As common and even clichéd as it’s become on social media, prayer is becoming more rare in Americans’ lives. According to the Pew Research Center, “fewer than half of U.S. adults (45%) say they pray on a daily basis. By contrast, nearly six in 10 (58%) reported praying daily in the 2007 Religious Landscape Study, as did 55% in the 2014 Landscape Study. Roughly one-third of U.S. adults (32%) now say they seldom or never pray, up from 18% who said this in 2007.”

If prayer is to have the power that Biden and Eisenhower assigned it, it’s time that we depoliticize it and revitalize its purpose by returning to the idea of prayer as intentional, private thought. The use of prayer as a strategy to manipulate audiences can diminish its authenticity and power for individuals across faiths and spiritual belief systems.

There are public figures who make genuine use of prayer or who respect its sacredness. Biden’s remarks at the prayer breakfast included mention of comrades who have died in the past year, among them Sen. Bob Dole. Biden delivered the eulogy at Dole’s funeral in December before a cathedral full of mourners, including Dole’s widow, Elizabeth Dole, an ardent prayer.

President Joe Biden speaks at the National Prayer Breakfast, Feb. 3, 2022, on Capitol Hill in Washington. (AP Photo/Patrick Semansky)

As a former senator herself and past president of the American Red Cross, Elizabeth Dole has relied on prayer when facing challenges. “To me it’s very important to know I have a source of strength beyond my own. When I’m undertaking a difficult assignment or making a tough decision, I’m glad I don’t have to rely on my own energy, wisdom, and judgment,” said Dole.

Prayer certainly has long had a place in our national life. The U.S. Constitution links prayer, God and religion. “The Star-Spangled Banner” was written in 1814 for elite ballroom dinners preceded by a prayer. Irving Berlin’s “God Bless America,” which he originally wrote in 1918, later became a second national anthem and is performed at sporting events and on the radio.

But as someone who researches prayer, I see its power to bring people together, but also its use to prompt divisiveness.

The U.S. Supreme Court recently agreed to hear Kennedy v. Bremerton School District, a case involving an assistant high school football coach at a public high school in Washington state who was fired for kneeling on the 50-yard line and openly praying after games. This violation of freedom of speech versus religious endorsement makes prayer the scapegoat.

During the Jan. 6 insurrection in 2021, white nationalists used prayer, Christ and the Bible to justify their dangerous actions. History shows the religious right started the anti-abortion movement in response to desegregation and the banning of organized prayer in public schools in the 1960s and ’70s.

Prayer is much bigger than any religious belief system, political stance or social issue. It pervades societal and cultural systems and ought to bring individuals from all disciplines and countries together.

Interfaith leader Eboo Patel writes in his book “Acts of Faith” that prayer transcends political party lines and religious affiliations. Leaders like the Dalai Lama, Deepak Chopra and Don Miguel Ruiz are prayerful people of different faiths.

RELATED: At National Prayer Breakfast, Biden calls for unity

Many may consider prayer as the power of being in the now and looking at reality. It makes us self-aware and present. What all prayers have in common is to pull the prayer away from the world and to be within yourself and to take stock in where you are and what your values are.

Reportedly, a graduate physics student asked Albert Einstein for ideas about a potential dissertation topic. “Dr. Einstein, I am supposed to research a topic upon which no one else has written, but it seems as if every possible area of inquiry has already been taken. What should I write about?”

Einstein, who had been asked earlier, in 1936, by a young student if scientists prayed, replied, “Find out about prayer, someone needs to find out about prayer.”

(Katie Greenan is an assistant professor of communication at the University of Indianapolis and a Public Voices Fellow through The OpEd Project. She holds a doctorate in educational leadership and policy studies. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)