(RNS) — Black History Month can often feel tokenized, more symbolic than substantive. One of the most compelling aspects of our journey as a country in the past few years has been to understand that the Black experience is utterly intertwined with the idea of America, not compressible into a month of meditation on a separate history.

Abrahamic faith communities have played a significant role in this journey. Christians especially have examined how slavery and segregation were long theologically justified and eventually condemned. The Black church provided the moral compass on the long walk to freedom, while Jews stood beside them in the struggle for racial equality. Islam played its own part in the lives of slaves and was there when African Americans turned away from Christianity, the faith of their enslavers.

But the role of Hindus and Hinduism in the Black experience isn’t as widely discussed, and even many American Hindus remain unaware of the connection. Because immigration from Asia was significantly limited for 41 years of the 20th century — just as the United States was in the deepest throes of the civil rights era — Hindus don’t often think of themselves or Hinduism as having an influence.

But the connections between American civil rights and Hinduism are precisely why more Hindus and Hindu temples should celebrate Black history, not least as a means of understanding their own story in America.

RELATED: Howard Thurman, mentor to King on nonviolence, featured in documentary

It starts with stories such as the Hindu monk Swami Vivekananda’s condemnation of segregated train cars in Tennessee during his visit to the United States in 1894 and his refusal to sit in a train car for whites. He understood that the invitation to sit in a whites-only car was only afforded because of his wealthy white hosts, and was not extended to others with dark skin.

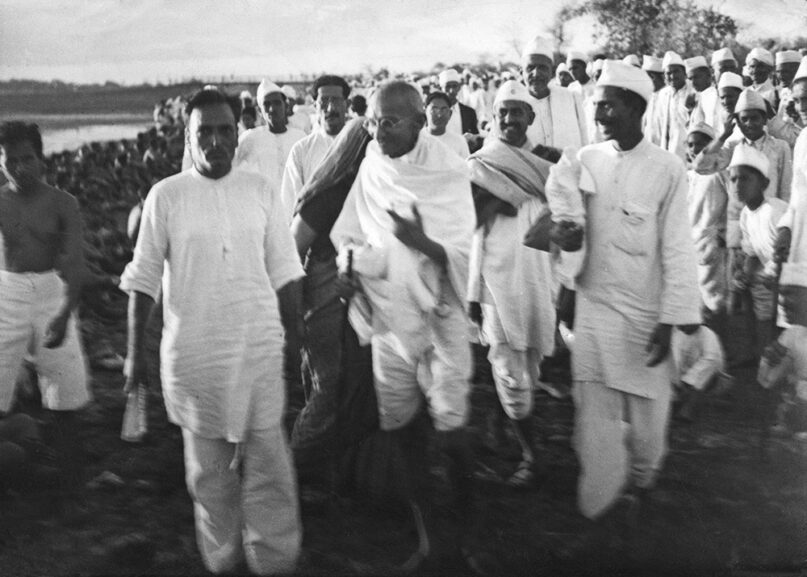

Many Americans are aware that the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s life-changing 1959 visit to India sparked a spiritual connection with Mahatma Gandhi. Though Gandhi was assassinated more than a decade before Martin and Coretta Scott King arrived in India, King learned how Gandhi used the Bhagavad Gita, one of Hinduism’s most widely known scriptures, as a basis of tying one’s dharma to social action.

It’s one of the reasons why the King Center for Nonviolent Social Change in Atlanta includes Gandhi’s walking stick and a copy of the Gita. As a Christian, King also came to see how issues like caste injustice in India contravened Hindu teachings through his conversations with Gandhians and Swami Vishwananda, a Hindu monk who, like Gandhi, was committed to ending untouchability.

The Gandhian way — and how King came to understand the dharmic concept of ahimsa, or nonviolence — shaped a generation of civil and human rights leaders in the United States in their quest for racial equality. King paid homage to the universal quality of divinity at a sermon in Montgomery, Alabama, when he said, “O God, our gracious heavenly father. We call you this name. Some call thee Allah, some call you Elohim. Some call you Jehovah, some call you Brahma.”

Even today, many African American civil rights leaders and elected officials highlight Gandhi’s impact and the role of Hindu teachings in the formation of a nonviolent movement dedicated to lasting social and political change.

While King’s visit to India was hugely consequential to his personal growth and in imparting the lessons of satyagraha, or nonviolent resistance, within an American context, he wasn’t the first American to seek answers from Hindu teachings on how to tackle racial injustice. Nearly four decades earlier, W.E.B. Du Bois sought counsel from a fiery Hindu reformer who led the resistance against British rule.

Du Bois began a long correspondence with Lala Lajpat Rai, a turbaned Punjabi Hindu who was one of the vocal leaders of a Hindu movement known as Arya Samaj, which argued that social issues such as gender inequality or caste were not part of the Vedas. Of the organized sects of Hinduism, Arya Samaj today still has among the highest number of women priests.

Du Bois sought parallels between the oppression of Indians by the British and that of African Americans by whites, arguing that Christianity in the West was merely legitimizing the persecution of Blacks and other “darker peoples.” Rai explained some of the core facets of Hindu teachings to Du Bois, who began to regard the universal struggle for liberation as more than national and geographic phenomena.

His exploration of India and Hinduism affected Du Bois so greatly that the latter wrote a novel, “Dark Princess,” in which the protagonist, a Black man named Matthew Towns, marries a Hindu princess named Kautilya, uniting the “darker races” in their struggle against European imperialism. Du Bois saw the union as a metaphor for uniting Indians and African Americans, and others, in a larger struggle. As a result, Du Bois himself became increasingly disenchanted with the more moderate aims of the NAACP, an organization he had co-founded decades earlier.

While Du Bois dedicated the book’s release to Rai, his friend was unable to read it. Rai was beaten by British authorities during a protest and died from his injuries several weeks later. Yet his influence on Du Bois and a generation of Black globalists who emerged during the 1930s and 1940s was undeniable.

As the late human rights activist E.S. Reddy once told me, both Du Bois and King were seeking something that American and Christian ideas alone were unable to provide. Their engagement with Hindu leaders and Hindu teachings would help to connect them to a larger idea of righteous action in a global context.

RELATED: How Heschel and King bonded over the Hebrew prophets

Over the next few decades, other Black Americans would go through their own similar spiritual journeys, including a few who would ultimately adopt Hinduism as their faith. That included the musician Alice Coltrane, who took on the name Turiyasangitananda, and late 1960s political activist John Favors, who became Bhakti Tirtha Swami, one of the first Black spiritual Hindu leaders in the United States.

This is why the importance of celebrating Black history is so important to understanding our own connection to our faith traditions. For Hindus, especially those from South Asian backgrounds, to appreciate their own mark on American history, it’s time to wholeheartedly celebrate the Black experience in America.

(Murali Balaji, an award-winning journalist, is a lecturer at the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania and author and editor of several books, including “Digital Hinduism” and “The Professor and the Pupil,” a political biography of W.E.B. Du Bois and Paul Robeson. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)

This column is produced by Religion News Service with support from the Guru Krupa Foundation.