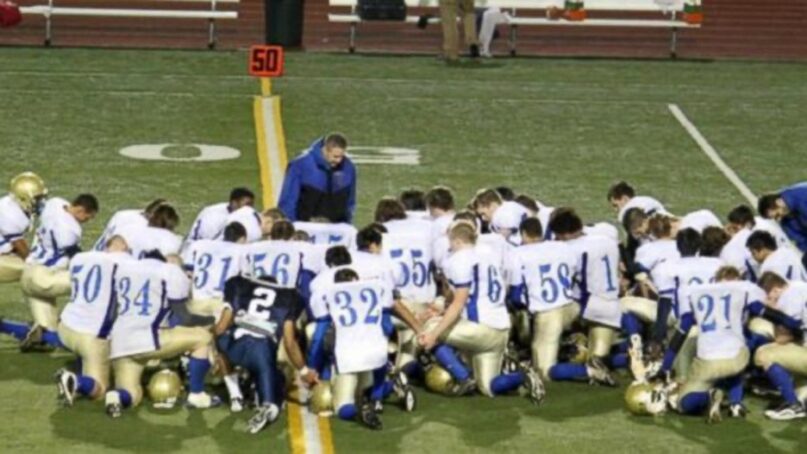

(RNS) — In a couple of weeks the Supreme Court will hear oral arguments in the case of a Washington state high school football coach who was dismissed for praying at the 50-yard line after games. Based on existing precedent, the coach has no case. But maintaining existing precedent is not the object of this exercise.

Joseph Kennedy was hired in 2008 to serve as an assistant coach at Bremerton High School. An evangelical Christian, Kennedy took to saying a prayer on the field after games. In due course some team members gathered round him and he began giving inspirational religious talks. He led locker room prayers.

This religious activity continued until September 2015, when a coach from an opposing team informed the Bremerton High School principal that Kennedy had asked his team to join him in prayer on the field. Whereupon the Bremerton School District, concerned about violating the First Amendment’s establishment clause, instructed Kennedy to cease and desist.

“Student religious activity,” the district said, “must be entirely and genuinely student-initiated, and may not be suggested, encouraged (or discouraged), or supervised by any District staff.” That’s the state of the law today.

Although Kennedy wasn’t happy, he initially followed the school’s instructions — stopped praying in the locker room, omitted religious references in his inspirational talks and prayed on the field only after the stadium had emptied. But then the school district received a letter from his lawyers.

His prayers were not obviously Christian, it claimed. They occurred after his official duties had ceased. They were private speech. The district could not prohibit him from praying with students if they voluntarily joined. He would resume praying at the 50-yard line after games.

Kennedy went to the news media with his position, declining the district’s offer to accommodate his need to pray by providing a private space for him to do so. He was suspended from his position and at the end of the season didn’t reapply for it. He did, however, file suit.

U.S. District Judge Ronald B. Leighton — for the record, a George W. Bush appointee — was unimpressed:

Like the front of a classroom or the center of a stage, the 50-yard line of a football field is an expressive focal point from which school-sanctioned communications regularly emanate. If a teacher lingers at the front of the classroom following a lesson, or a director takes center stage after a performance, a reasonable onlooker would interpret their speech from that location as an extension of the school-sanctioned speech just before it. The same is true for Kennedy’s prayer from the 50-yard line.

Granting the school district’s motion for summary judgment, Leighton found that Kennedy’s religious behavior violated what’s known as the endorsement test. First advanced by Justice Sandra Day O’Connor in 1984, it finds a violation of the establishment clause if “a reasonable, informed observer” would conclude that some religious behavior or display indicates public endorsement or disapproval of religion.

“But even more than the perception of school endorsement,” wrote Leighton, “the greatest threat posed by Kennedy’s prayer is its potential to subtly coerce the behavior of students attending games voluntarily or by requirement. Players (sometimes via parents) reported feeling compelled to join Kennedy in prayer to stay connected with the team or ensure playing time, and there is no evidence of athletes praying in Kennedy’s absence.”

Upholding Leighton’s decision, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals declared, “To answer this question, we must examine whether a reasonable observer, aware of the history of Kennedy’s religious activity, and his solicitation of community and national support for his actions, would perceive [the Bremerton school district’s] allowance of Kennedy’s conduct as an endorsement of religion. Although there are numerous close cases chronicled in the Supreme Court’s and our current Establishment Clause caselaw, this case is not one of them.”

Petitioning the Supreme Court to review the case, First Liberty Institute, the conservative Christian legal outfit representing Kennedy, protested the school district’s accommodation offer on the grounds that it was “effectively banishing religious expression from public view.” As its press release puts it, “Banning a coach from praying, just because he can be seen by the public, is wrong and violates the Constitution.”

That the court agreed to hear the case suggests that at least four of its six conservative justices want to move the goal posts when it comes to the establishment clause. They would, it seems, like to let public school teachers publicly promote religion on the job.

You may agree. I don’t.