PUNE, India (RNS) — In the first week of April, Shaheed Bhagat Singh Vichar Manch, a group dedicated to the ideas of Indian freedom fighter Bhaghat Singh, announced its seventh atheism conference would be held on April 10 in this sprawling city in western India. Within two days, the venue’s 350 seats were all booked. Even though the annual event had not taken place for two years due to the coronavirus pandemic, the organizers were surprised by the tremendous response.

But soon members of the group began receiving threats on Twitter from Hindu nationalists, objecting to holding a meeting of atheists on Ramnavami, the birth anniversary of the Hindu god Ram, which fell on the same day.

After getting calls from local authorities, said Nitin Hande, a member of the organization, “Police denied the permission to host the event on April 10, saying that they had pressure from many right-wing fringe groups. We had to postpone the event to April 24.”

On April 24, a number of seats at the conference were empty, and many attendees told organizers that they were scared of Hindu nationalist violence.

RELATED: In India, Muslim hawkers attacked at Hindu temple fairs

Of India’s 1.4 billion people, fewer than 33,000 are self-declared atheists. Freedom of speech, religion and conscience guarantees in India’s Constitution protect atheists, said human rights lawyer Asim Sarode. Article 51A (h) assigns all Indian citizens a duty to develop “scientific temper, humanism and spirit of inquiry and reform.”

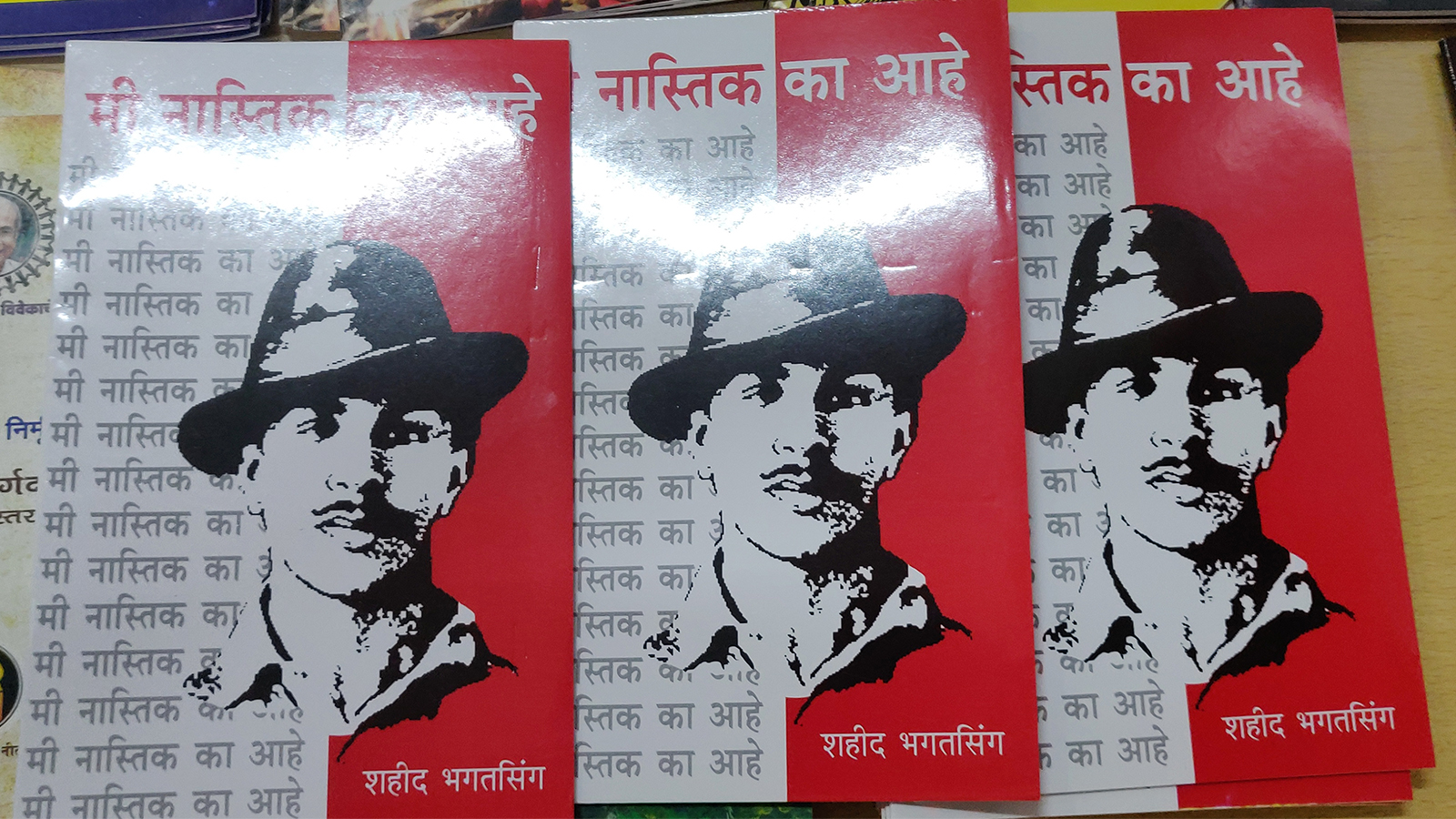

Atheism’s history in India dates back to the fourth century B.C. and the Charvaka, or Lokayat, school of philosophy, said Sadanand More, a writer and poet who heads the philosophy department at Savitribai Phule Pune University. Bhagat Singh, who was executed by the British in 1931 and inspired the Shaheed Bhagat Singh Vichar Manch, is remembered for his essay “Why I Am an Atheist,” still widely read today.

Copies of the book “Why I Am an Atheist” by Indian freedom fighter Bhagat Singh. Photo by Varsha Torgalkar

But being an atheist in India has become more difficult with the rise of the Hindu nationalist or Hindutva movement and the success of its political wing, the Bharatiya Janata Party. Since the BJP won national elections in 2014, attacks on anyone who holds minority beliefs, including Muslims, Christians, Dalits and nonbelievers, have increased. Recently, Hindutva activists have called openly for the genocide of Muslims.

Seema Nayak, 42-year-old engineer from Maharashtra state, said she has been atheist since childhood.

“I have always refused to participate in religious festivals and rituals as it’s against my logic. I did not allow them to perform certain pujas for my son,” she said, referring to Hindu rituals. Her rejection of religion has drawn criticism from her in-laws and others. “Many of my relatives don’t talk to me. But I have maintained my stand that I will not participate any religious event, even to please my relatives.”

Though her husband is also an atheist and supports her, Nayak said atheism is often harder for women, who are expected to carry forward religious traditions in the family.

A 66-year-old retired professor from an engineering college in Pune who asked to remain anonymous for fear of backlash from his Muslim community said he was barred by religious leaders from participating in his mother’s funeral when she died in 1997. When his father died in 2017, he informed the local media and police to prevent protests at the funeral. Still, he is afraid his family members might face social boycott from the community if his atheism becomes public.

People attend an atheism conference in Pune, India, on April 24, 2022. Photo by Varsha Torgalkar

Being an atheist, said the professor, “gives you a support system, and you know you have people to go when the community ostracizes you.” But he said atheists could use more support, suggesting that a help line and online resources could create a safer environment for nonbelievers.

RELATED: Ancient Indian temples are designated ‘iconic,’ worrying preservationists

Jaswant Zirakh, a member of the Tarksheel Society, a 40-year-old organization in Punjab with more than 1,000 members across the state, said that, by and large, Indians are comfortable with atheist ideas. He said threats come not only from the BJP but from popular religious leaders, colloquially known as godmen, who attack atheism out of fear of losing power and income.

“Common people in urban and rural areas, and even kids, listen to our programs where we (discuss) whether God exists or not and how religions exploit them,” said Zirakh. But “so-called godmen, astrologers and tantric gurus … spread rumors about our work and atheism, saying atheists are no good people. Sometime they create ruckus at the events.”

This article is produced by Religion News Service with support from the Guru Krupa Foundation.