(RNS) — When Madame Pamita was little, her mother told her stories about her Ukrainian grandmother — how she would pour wax into water to heal the sick; how once when Madame Pamita’s mother was very sick, her grandmother made a doll for her to hold, which disappeared after she got well.

Those stories became little mysteries for Madame Pamita. The clues to unlock her grandmother’s magic were hard to find — while she considers herself a witch as well as a member of the Ukrainian diaspora, Madame Pamita doesn’t read or speak Ukrainian, and she says that little about Ukrainian folk magic was written or preserved during the Soviet era.

Then she stumbled on a book about Ukrainian wax-pouring healing at a friend’s bookstore. It was like “opening the Cave of Wonders,” she said.

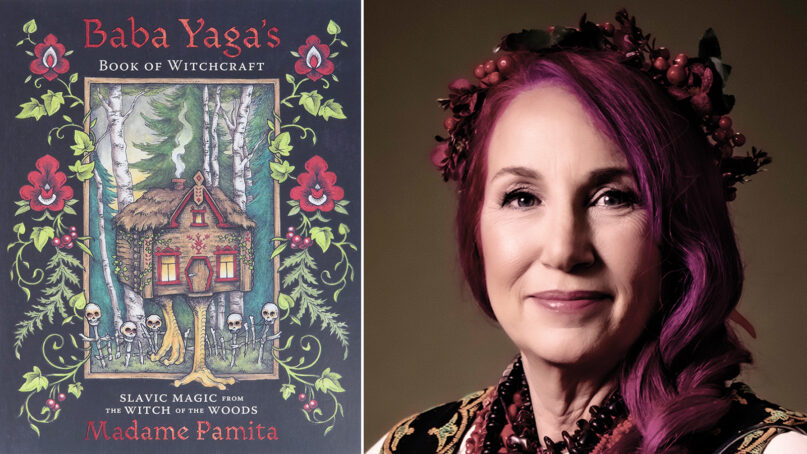

In the years since, Madame Pamita has collected dozens of ancient and modern Slavic magical practices, which she has compiled as a new book: “Baba Yaga’s Book of Witchcraft: Slavic Magic from the Witch of the Woods.” She also hosts an accompanying podcast called “Baba Yaga’s Magic” and owns an online witchcraft store called Madame Pamita’s Parlour of Wonders.

RELATED: How to help Ukrainians today: Organizations providing aid

Baba Yaga is a witch figure who flies around Slavic folk stories in a giant mortar, pestle in hand, and lives in a hut that stands on chicken legs deep in the woods.

Madame Pamita. Courtesy photo

As the COVID-19 pandemic began, Madame Pamita said, it felt as if the spirits of her Ukrainian grandmother and of Baba Yaga were urging her to write. When Russia invaded Ukraine in February, just before “Baba Yaga’s Book of Witchcraft” was scheduled to release, she said it made sense.

“The evidence of that spirit work is the fact that this book came out exactly at the time that it was so needed,” she said.

Madame Pamita spoke to Religion News Service about Baba Yaga, traditional Slavic magic and how the author is using her magic to support the people of Ukraine amid Russia’s continuing invasion of the country.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Who is Baba Yaga?

In Soviet times, in particular, and the 20th century, you would hear about her being a Russian witch. But Baba Yaga shows up with many different names. We see her called “Egi Baba,” “Jezibaba,” “Iagonishna” — all these kinds of weird names and variations of names, depending on the language and the region — which tells us she’s actually pan-Slavic and she’s very, very, very old.

She’s always a secondary character in stories — usually an antagonist or a donor. She’ll show up in some stories like this ogre, like the witch in “Hansel and Gretel.” We also see her showing up kind of ambiguous. And in some stories, we see her as a donor figure where the heroine or the hero will go to her and she’ll give information or she’ll give a special magical gift that the hero or heroine needs to achieve their goals.

So which witch is she? Is she the villain she’s often made out to be?

I don’t think she was ever Glinda the Good Witch. In my experience of connecting deeply to her, I see her as a grandmother figure, but a tough grandma, or like a grandma who knows you can do more than you think you can, so she pushes you.

If we go back far enough, we see her as the mistress of the forest, the grandmother of the forest, the mother of the forest, as protector spirit of the forest. She’s that person who is connected to the world of the dead and the world of the living. She moves between those worlds, which is why sometimes she’s going to kill the person or she’s going to put them in the fire.

In Slavic practices, the fire was alive, and the fire was where the ancestors were. We in the 21st century don’t have the depth of knowledge about what it means to get put in the fire. It means to go to your ancestors. So she’s sending you to the world of the spirits if she’s trying to put you in the wood stove.

In “Baba Yaga’s Book of Witchcraft,” you write about the embroidery that appears on the traditional Ukrainian clothing we’ve seen at demonstrations supporting Ukraine or at Ukrainian Masses. Can you explain its significance?

For diaspora Ukrainians, like myself, it’s a way to connect to our homeland, to our family and our people, and there’s a great sense of pride in wearing your “vyshyvanka.”

But there’s also an underlying sense that there’s magic in that embroidery. Each of those shapes would have a significance that a stitcher may have known, going back thousands of years. These stitches would have specific meanings of blessings or protection or fertility or whatever. And so you would create the shirt with an intention.

A young girl dressed in traditional Ukrainian attire attends an Orthodox Easter service, Sunday, April 24, 2022, in Bucharest, Romania. RNS photo by Alexandra Radu

Even the process of making the shirt — Ukrainians sing when they weave because they’re singing incantations and blessings into that cloth. Then while you’re stitching, you want to come with a pure mind, with a peaceful mind. You don’t want to come with anger or anxiety when you’re stitching because then you’re encoding that into your talismanic clothing, which is a terrible idea.

I’ve seen cross-stitch patterns that people are stitching in solidarity with Ukraine, including traditional Ukrainian designs or sunflowers. Some reference things that have happened during the Russian invasion. Is there magic in stitching?

I’ve been stitching like crazy since this war has happened as a way of encoding protection, and I do a visualization where I imagine a big tidal wave going over the heads of the Ukrainians and pushing the Russian people back across the border.

The stitching for me has been so therapeutic when I’m like, “I’ve got to do something” (about the war). It feels very meditative, and you have to focus because you’ve got to count those stitches, but you also get to enjoy that repetitive process, and you could say a prayer over each stitch.

Even the stitches themselves have a power. The “X” of the cross itself — that equal-armed cross — is seen as a sign of protection. When you make the stitch, you can actually encode what it is that you want with the first stitch and then seal it in with the second stitch.

So it’s quite a powerful thing. I believe everything that we do energetically — if you’re focusing on something, it brings something. So if you’re focusing on Ukraine as you stitch and sending them blessings and protection, that has power.

What other practices particularly surprised you?

There is a chapter (in the book) about spirit dolls — “motanka.” That showed me this connection between what my grandmother was doing with my mom, putting this little doll in her bed when she was sick.

As I found out more, it was almost like I kept uncovering treasure. I felt like Indiana Jones because everything was pretty much new to me. Some was going deeper into something I already sort of knew — like “pysanky” (painted eggs). We all know pysanky are magical, right? But I didn’t know how deeply magical.

RELATED: EXPLAINER: How is Russia-Ukraine war linked to religion?