(RNS) — A long-haired man in skinny jeans is greeted by cheers, raised hands and an orange-tinted spotlight as he steps onto a platform. “If you want to succeed in this world, you have to build something that has intention,” he says, microphone in one hand and gesturing energetically with the other. “And what puts us together, all of us here, is because we want to do something that actually makes the world a better place.”

A megachurch pastor? Self-help guru? No, it’s Adam Neumann, former CEO of WeWork, the infamous co-working office startup, as captured in Hulu’s 2021 documentary “WeWork, or the Making and Breaking of a $47 Billion Unicorn.”

When WeWork’s intended initial public offering failed in 2019, financial questions were only part of what sent the company spiraling. Its reputation had already been shaken by Neumann’s declarations in its filings about “the energy of we—greater than any one of us but inside each of us” and for the company’s vow to “elevate the world’s consciousness.” In earlier days, WeWork executives got instruction from leaders of the Kabbalah Centre, whose values are loosely based on Jewish mysticism.

Years before the IPO filings cued eye rolls over the firm’s spiritual promises, Neumann had cited “energy and spirituality” as the best metrics to gauge the company’s value. Eventually the IPO was withdrawn, the stock crashed and Nuemann resigned as CEO.

But Neumann was onto something. As corporations compete for the best of a new generation of young workers, they are finding that the price for productivity and loyalty is meaningful community and higher purpose.

An August 2020 survey by the management consulting firm McKinsey & Co. found that a staggering 70% of more than 1,000 U.S. employees said their work defines their sense of purpose. In 2018, professional coaching startup BetterUp surveyed more than 2,000 professionals across 26 industries and found that 9 of 10 employees would take less pay for more meaningful work.

As Neumann’s former assistant, Megan Mallow, asks the makers of the “WeWorked” documentary, “Why did it feel like, not that I lost a job, but like I lost my purpose?”

While some corporations have been accommodating employees’ spiritual values since the 1970s, the idea that the workplace should feed the soul only arrived along with the millennials, who began entering corporate life roughly two decades ago, experts say. Though often less religious in their private lives, they brought expectations that work would provide a calling, not just a paycheck. Those whose faith is an integral part of their lives, meanwhile, want their values to be recognized if not adopted by corporate leaders.

“When you go to work six days a week, you can’t compartmentalize your life and keep your challenges outside of your work,” said Greg McBrayer, a chief flight dispatcher for American Airlines, who is also a chaplain for the carrier.

Glean Network founder Elan Babchuck leads a group session in 2017. Photo by Melanie Einzig

Elan Babchuck, a rabbi and entrepreneur who launched the Glean Network in 2016 for employers looking to combine their spirituality with work, said that employees who don’t see their values reflected at work are the first to leave. “Burnout happens not just because you work too much, but because you can’t show up whole. You’re not seen as a whole person,” said Babchuck. “You are treated in a utilitarian way. You are objectified.”

Breaking down barriers between work and spirituality benefits not just employees, but the bosses’ bottom lines.

“Research shows and company experience shows that where diversity is welcomed and you can bring your whole self and whole soul to work, you get much more productivity because people feel at home,” said Brian Grim, president of the Religious Freedom and Business Foundation. “That creates much better working relationships, more commitment, which turns into a lot more profitability.”

If the work itself doesn’t provide meaning, many companies are encouraging employees to create it themselves.

At Tyson Foods, a Meals that Matter disaster relief team brings employees together to donate meals on-site to feed families who have lost property or livelihoods, as well as relief workers. “The team members I’ve worked with,” said Pat Bourke, manager of corporate social responsibility at Tyson Foods, “and I’ve worked with hundreds in the last 10 years or so in disaster relief, say it is a great sense of pride to know they work for a company willing to make the investment and respond to these disasters.” Tyson also has 100 chaplains on staff.

Karen Diefendorf, second right, director of Chaplain Services at Tyson Foods, talks with employees at the company’s Berry Street poultry plant in October 2018 in Springdale, Arkansas. (Logan Webster/Tyson Foods via AP)

Other companies invest more in helping employees nurture their spiritual side, retaining spiritual gurus and yogis or sending staffers on wellness retreats. Silicon Valley Wellness, a holistic life vendor in the Bay Area, offers on-site workshops on emotional well-being or attention management as well as meditation teachers. Netflix dedicates some of its office space to plush mental break rooms that can be used for daily prayer.

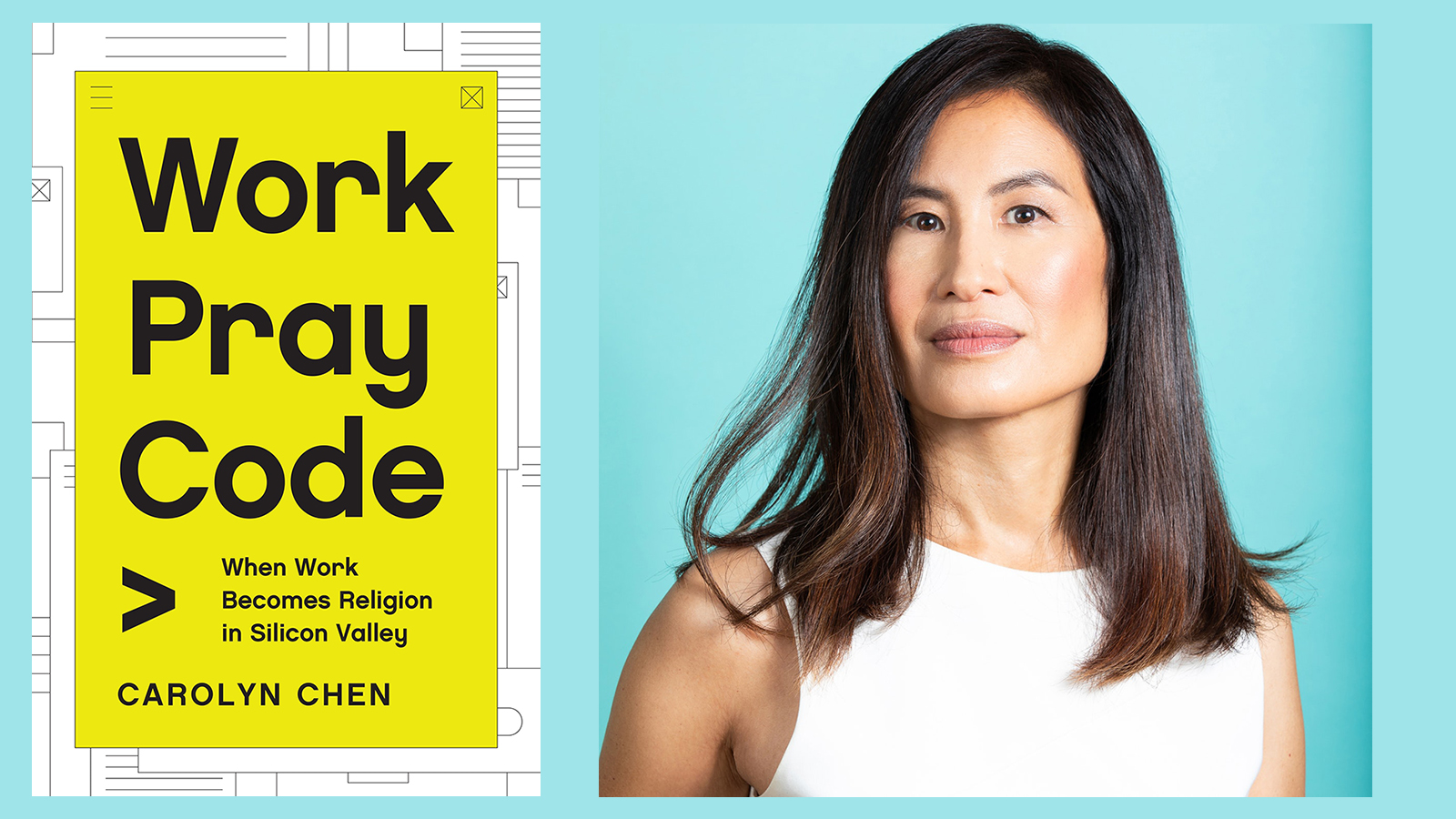

In her new book “Work Pray Code: When Work Becomes Religion in Silicon Valley,” scholar Carolyn Chen, a sociologist and professor of ethnic studies at the University of California, Berkeley, argues that there can be real risks to letting our work provide meaning.

“We’re seeing that high-skilled professionals are turning to work for belonging, identity, meaning, purpose and fulfillment. And these are the very things that Americans once turned to religion for,” she told Religion News Service.

Chen said work is especially likely to replace religion in hubs such as Seattle, Portland, Cambridge and Silicon Valley, where religious affiliation is much lower than in other parts of the U.S.

RELATED: How Silicon Valley’s ‘Techtopia’ turned work into religion

“When you shift your meaning to the workplace, you shift it away from other institutions,” Chen explained. “It might be the family, neighborhood, it might be your church, your synagogue or other social institutions.” People who attended a house of worship, meanwhile, were less likely to find their identity in their work; it was anchored elsewhere.

Chen, who talked to more than 100 Silicon Valley workers between 2013 and 2018, believes that as the workforce absorbs functions traditionally found in religious spaces — chaplaincy, volunteerism, community — it acts as a drain on the rest of society, with highly skilled workers disproportionately investing time, energy and resources into their work.

She also argues that it exacerbates inequity in the workforce.

“Work is becoming more rewarding and fulfilling for a certain sector of high-skilled workers, and less meaningful and less dignified for everyone else,” she said, pointing to how inaccessible the “utopian workplaces” of Silicon Valley are for many.

“People have experienced this wholeness in the workplace which we would think is a really good thing. What’s wrong with that? But then there are these social consequences you don’t see when you’re in the middle of it.”

“Work Pray Code: When Work Becomes Religion in Silicon Valley” and author Carolyn Chen. Courtesy images

Chen’s point is backed up by data. McKinsey’s survey found that while more than two-thirds of all workers found purpose in their work, executives were almost eight times more likely than other employees to say so.

According to Chen, the only way out is to reinvest in civic institutions. “The only way to stop worshipping work is essentially you need to worship something else,” Chen said.

This theory has proven to be the case for Cam Coulter, a senior analyst at the digital accessibility consulting company Level Access. Coulter tests websites and apps to ensure the tech is accessible to folks with disabilities.

“I wanted to do work that had a clear sense of doing good for the world,” said Coulter. “Digital accessibility is a really good fit for me, because I get to do something that’s doing good for people, stays true to being service-minded and supports people with disabilities.”

But Coulter doesn’t view work as the most important part of their life. Coulter primarily finds meaning in time spent with their partner, friends and family, as well as with their local church community and in the company of other advocates working to expand affordable housing.

Regardless of a person’s religious affiliation, the trick seems to be finding fulfillment in work without making the brand a religion or the CEO a messiah. “This sense of self-fulfillment from work, I don’t like to institutionalize it,” said Leticia Lourenco, a nonreligious Netflix employee whose job includes making the field of cybersecurity more collaborative and inclusive. “I like to keep it as something private, rather than collective.”

RELATED: Religious diversity: Corporate obstacle? Or asset?