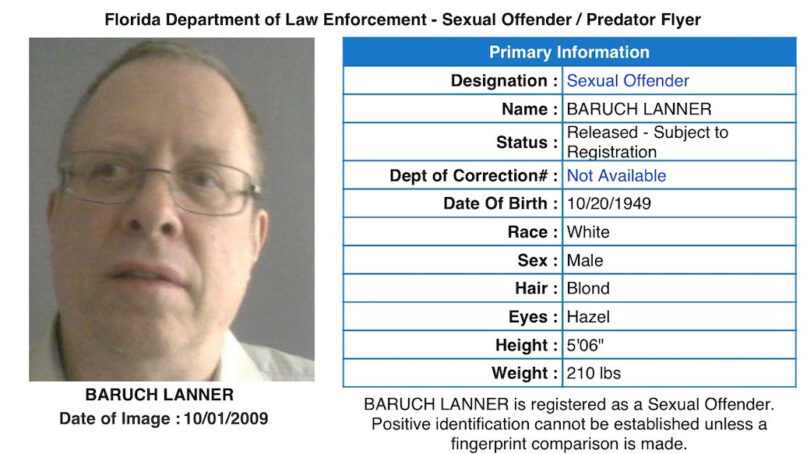

JERUSALEM (RNS) — In 2019, Baruch Lanner, a former rabbi convicted of sexually abusing students at a New Jersey high school in the 1970s and 1980s, began delving into the possibility of applying for Israeli citizenship.

Before long, Shana Aaronson heard about it.

“I was contacted by people in the community in the U.S. and also here,” said Aaronson, director of Magen, an organization that deals with sexual abuse in the Orthodox Jewish community in Israel. “People who knew him or knew of him.”

When Lanner, a former Orthodox rabbi, youth director and school principal who served three years in prison, showed up in Israel earlier this year on a tourist visa with the intent of moving to the country permanently, Aaronson and Hannah Katsman, another advocate for sexual abuse victims, sprang into action. They launched a grassroots campaign to pressure the Israeli government to deny him citizenship.

Their online petition, as well as pleas from hundreds of Orthodox and non-Orthodox rabbis, Jewish community leaders and others, yielded results. On July 20, Ayelet Shaked, Israel’s minister of the interior, denied Lanner’s citizenship bid but stopped short of canceling his tourist visa.

Aaronson said the response to Lanner’s arrival from the public and the Israeli government reflects the growing, if uncomfortable, realization that Israel has become a refuge for Diaspora and Israeli Jews accused or convicted of sexual misconduct.

RELATED: 4 women sue Orthodox Union and its youth group, alleging sex abuse by rabbi

Shana Aaronson. Photo courtesy of Magen

“I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to say that Israel is a safe haven for Jewish sexual offenders,” Aaronson told Religion News Service. “There are about 100 cases that we know of, the vast majority Orthodox.”

Some of these offenders immigrated to Israel, while others are Israeli citizens who perpetrated abuse while living abroad and then returned to Israel.

Manny Waks, a survivor of and activist against sexual abuse in the Jewish community, listed several reasons why offenders seek refuge in Israel. The first, he said, is the country’s Law of Return, which allows Jews, or people who can prove that at least one of their grandparents was Jewish, to apply for citizenship.

While the immigration process is long and bureaucratic, “there are many loopholes and opportunities for those who wish to deceive the process to do so,” Waks said. Some people who want to hide their past apply for Israeli citizenship from a third country, while others, such as Lanner, enter Israel as tourists.

Even when an abuser’s record is public knowledge, people with influence within and outside Israel often exert pressure to allow the offender to move to Israel — a process known as “making aliyah” — or attempt to block the extradition of an Israeli offender.

Such was the case with Malka Leifer, an Israeli-born ultra-Orthodox educator who became the principal of a Jewish school in Australia. On Aug. 1 she will stand trial, accused of 70 counts of sexual abuse against eight children.

In 2008, just before an Australian arrest warrant was issued, Leifer fled back to Israel, where she was able to avoid extradition for 13 years, thanks to the protection of prominent rabbis and Israeli Health Minister Yaakov Litzman. She was finally extradited to Australia in 2021. Litzman, the ultra-Orthodox health minister, pleaded guilty to breach of trust and resigned from the parliament.

“The ultra-Orthodox community, the rabbis facilitated her escape to Israel and interfered on her behalf,” said Waks, who flew to Australia this week to attend Leifer’s trial.

In this Feb. 27, 2018, file photo, Israeli-born Australian Malka Leifer, right, is brought to a courtroom in Jerusalem. Leifer, a former school principal extradited from Israel after a lengthy legal battle, appeared in an Australian court on Sept. 13, 2021, to hear evidence behind child sex abuse charges against her. (AP Photo/Mahmoud Illean, File)

The activist attributed some of this support for Leifer to ultra-Orthodox fears that the accused won’t be able to lead a devout lifestyle during a trial and especially in prison. The community tends to be extremely insular, with unrelated men and women prohibited from socializing, even at work.

In Leifer’s case, “they don’t want a woman to sit in a ‘goyishe’ (non-Jewish) prison with male staff members,” Waks said.

“They think the food won’t be kosher enough,” Waks said. “Yet they’re putting the safety of their own children at risk” by protecting abusers.

Another concern, based on the history of Jewish persecution, is that a Jew won’t be given a fair trial in a secular court either within or outside of Israel.

Manny Waks. Courtesy photo

“They still have a shtetl mentality, with all the antisemitism and pogroms that really did put visibly Jewish people in danger,” Waks said. “Jews were falsely accused and treated unfairly.”

While this circling-the-wagons mentality has helped Jews survive over the millennia, “this is 2022,” Waks said.

Elana Sztokman, author of “When Rabbis Abuse: Power, Gender, and Status in the Dynamics of Sexual Abuse in Jewish Culture,” says Israeli and Jewish society and particularly the Orthodox community have recently begun to make real strides in the fight against sexual abuse — a previously taboo subject.

She credits some of this “grassroots awakening” and willingness to speak out against abuse to social media. Despite rabbinical mandates not to use social media for anything but religious studies — if at all — 64% of ultra-Orthodox Israelis are using the internet, compared with 28% in 2008, according to a December 2021 poll by the Israel Democracy Institute.

Online groups devoted to sexual abuse in the Jewish community, as well as groups devoted to women’s empowerment and activism, “are offering victims/survivors to connect with one another and to realize they’re not alone,” said Sztokman.

Sztokman called it “a pivotal moment” when, late last year, Israel’s ultra-Orthodox community openly shunned Chaim Walder after a secular newspaper reported that the popular rabbi, therapist and bestselling author in the ultra-Orthodox community had been accused of abusing many of the boys, girls and women he treated.

After a trial in a religious court that included testimony from more than 20 of his alleged victims, many ultra-Orthodox and mainstream booksellers refused to sell his books, and he was called “a threat to society.”

Walder, who denied the charges, died by suicide in 2021.

The community’s widespread anger at Walder “was something very new” and paved the way for the outcry at the arrival of Lanner, Sztokman said.

Despite the victory over Lanner’s citizenship, Aaronson said Israel needs to remove legal loopholes that enable sexual offenders to live freely in Israel.

“If the police don’t investigate, or a minister can give someone a visa, then what’s the point?” she said.

RELATED: As Reform Jews investigate themselves, a reckoning over sexual abuse grows