(RNS) — Growing up, when Steven Fine learned about the Kutim, the Samaritans, in the Talmud, the references “went in this ear and out the other.” In 1977, he met a Samaritan for the first time at one of the salons the late Jewish folklorist and Hebrew University professor Dov Noy hosted — “Every week, it was like going to the all-star game!” — but he didn’t meet just any Samaritan that day. Benny Tsedaka, who remains a friend, was the son of the community’s leader.

Suddenly, that biblical people — best known for the protagonist in Jesus’ famous parable of The Good Samaritan — became real to Fine, a college sophomore at the time.

Now a professor of Jewish history at Yeshiva University, Fine still has that biblical people on the brain, and Samaritans are having something of a cultural moment.

Fine co-curated the exhibit “The Samaritans: A Biblical People,” which opened Sept. 16 at the Museum of the Bible in Washington, and edited a new scholarly volume of the same title. He was academic adviser to the first-ever Samaritan cookbook in 2020 and to a new documentary about Samaritans by filmmaker Moshe Alafi.

Steven Fine at the sukkah in the Samaritan exhibit at the Museum of the Bible. Photo by Menachem Wecker

Also in 2022, the superhero film “Samaritan” starring Sylvester Stallone ostensibly pits — without too many spoilers — the good-guy Samaritan against evil brother Nemesis. The film takes for granted that viewers recognize the reference from Luke’s gospel.

In his parable, Jesus tells of a “certain Samaritan” who tends to the wounds of a man, whom bandits left for dead. Though a priest and Levite pass the victim by, the Samaritan loads him on his animal, takes him to an inn and settles with the innkeeper.

“Which of these three do you think was a neighbor to the man who fell into the hands of robbers?” Jesus asks, per the New International Version.

Today, every state in America has a version of a “Good Samaritan Law,” shielding those who provide emergency treatment from most malpractice suits. In an unlikely turn of fate, Tzili Charney, widow of Leon Charney, who was instrumental in creating New York’s Good Samaritan Law, has supported many of Fine’s Samaritan projects.

Photos of the Samaritan community on display at the Museum of the Bible. Photo courtesy of Museum of the Bible

Jeffrey Kloha, chief curatorial officer at the Bible Museum, cites the “Seinfeld” episode, in which the main characters are arrested under a Good Samaritan Law for not helping someone in need. “The Samaritans were an ancient tribe — very helpful to people,” Kramer (Michael Richards) explains. Kloha laughs off the latter clause but corrects the tense of the former. The Samaritans are not a relic of the past, but a living people.

That is the main lesson Fine and exhibit co-curator Jesse Abelman, the museum’s Hebraica and Judaica curator, hope visitors will take away from the show.

In an interview at the Bible Museum, which mostly transpired in Hebrew with a translator present, Yefet Tsedaka — whose brother Fine met in 1977 — said the Samaritan community is pleased with the exhibit, with which it was very involved.

Yefet Tsedaka at Museum of the Bible. Photo by Menachem Wecker

There are currently 862 Samaritans, up from 145 in 1917, according to Tsedaka. Most live either in the West Bank, on Mount Gerizim, which is sacred to them, or in the city of Holon, just outside Tel Aviv. Samaritans are not Jews but are part of “Am Yisrael,” the Israelite people. Each Samaritan, Tsedaka said, can trace back to which tribe — Ephraim, Menasseh or Levi — he or she comes from.

Samaritans have lived in the Holy Land since biblical times, according to Tsedaka, who once told former Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, “You are a guest of ours.”

Despite Samaritan longevity in Israel, the community has faced a “gender imbalance,” at times five men to every two women, according to Tsedaka. In a controversial move, his grandfather married a woman from outside of the community, which the then-high priest endorsed. She converted and, in part due to her dogged nature, became accepted in the community.

In recent years, Samaritan men have married Ukrainian women, who move to Israel, convert and join the community. Asked whether the war in Ukraine has impacted such matches, Tsedaka said the community is poised to face a different challenge. Having so zealously brought in outside women, Samaritans may have significantly more women than men within a decade or two. It is much more problematic from the community’s perspective for outside men to join.

“That will be for the high priest to resolve,” said Tsedaka.

The Museum of the Bible exhibit, which includes artifacts spanning from the second century before the Common Era to contemporary paintings made in the past couple of years, notes that Samaritans, who are mentioned in both Jewish and Islamic texts, have often clashed with both.

One wall text tells of 16th-century Huguenot Hebraist Joseph Scaliger, who requested texts from an Egyptian Samaritan community, only to have those texts lost in a shipwreck. They were recovered, sparking further Christian interest in Samaritans.

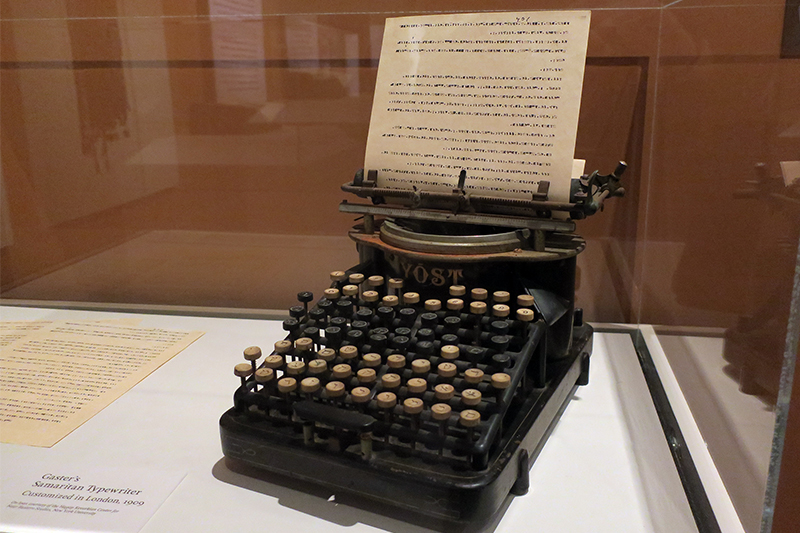

The customized Samaritan typewriter of Rabbi Moses Gaster, on display in the Samaritan exhibit at Museum of the Bible. Photo by Menachem Wecker

Another vitrine contains the custom typewriter that Rabbi Moses Gaster (1856 – 1939) used to correspond with Samaritans living in Nablus, at the base of Mount Gerizim. When he typed in Jewish Hebrew letters, the text was printed in Samaritan Hebrew letters. His penpal, Jacob, son of Aaron, the high priest, “saw an opportunity to harness Gaster’s academic platform and reputation to amplify Samaritan culture,” the wall text states.

The show highlights many Samaritan religious practices, which often resemble Jewish ones. Samaritans sacrifice paschal lambs annually, drawing many outside spectators. It is the only monotheistic group that still sacrifices animals, according to the documentary.

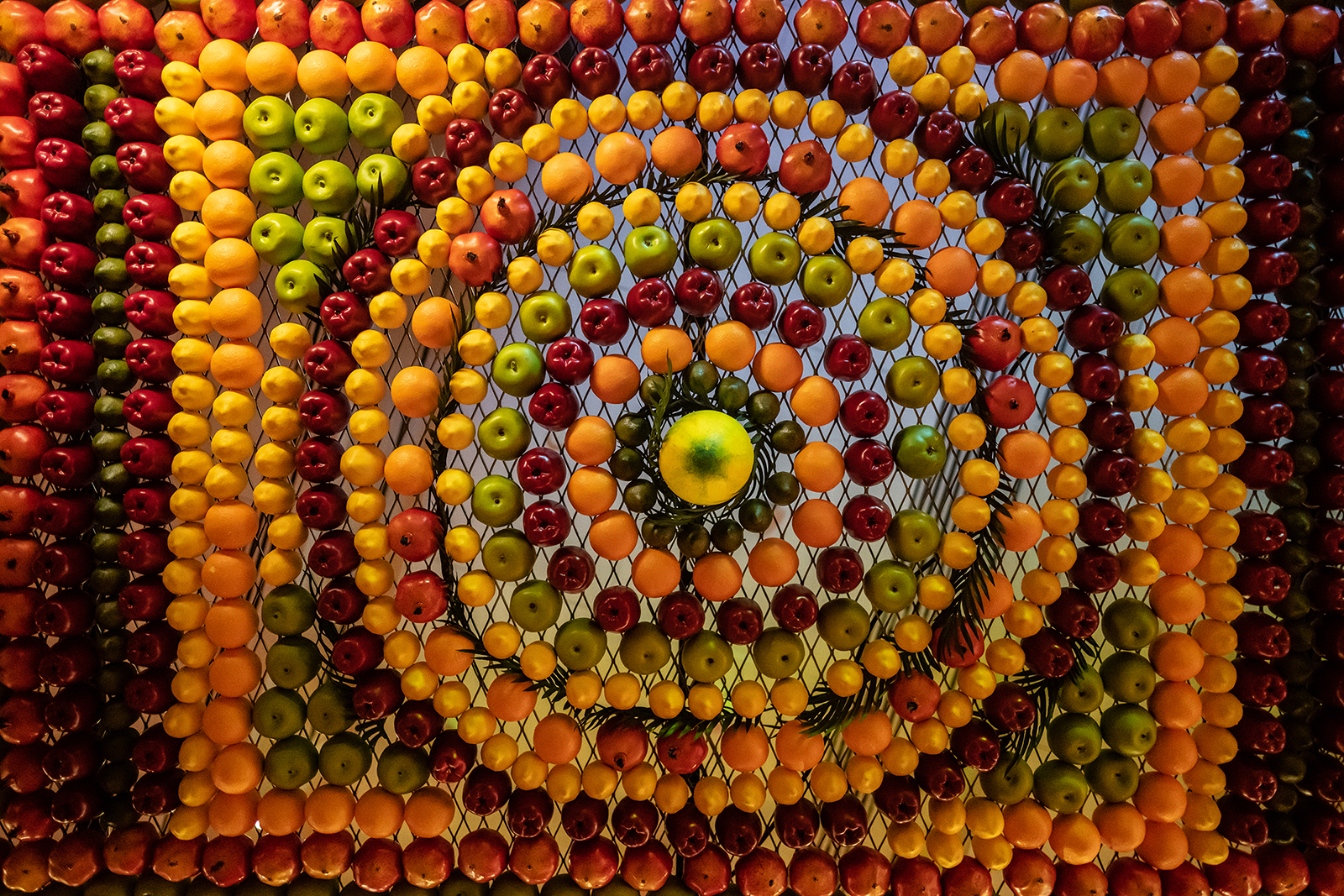

On the Sukkot holiday (Tabernacles), Samaritans build ritual huts. Whereas Jews typically build theirs outside — and avoid anything overhanging the top of the sukkah — Samaritans make them indoors and decorate them with fresh fruit. A Samaritan sukkah on display at the Museum of the Bible had plastic fruit, some of which the curators purchased from Hobby Lobby, according to Abelman. (Steve Green, president of Hobby Lobby Stores, is chairman of the museum’s board.)

Samaritans keep the Sabbath and ritual purity laws strictly, and they, too, hold the Torah sacred. But Samaritan and Jewish Scripture are not the same, and Samaritan religious leaders have ruled very differently than rabbis have on ritual matters over the centuries. Most dramatically, Samaritans hold sacred the mountain Gerizim — where the Samaritan high priest lives — whereas Jews have a different temple mount.

A Samaritan sukkah, created with plastic fruits for display purposes, at the Museum of the Bible. Photo courtesy of Museum of the Bible

Fine said the Samaritans are a “micro-people,” and have had a real chance of disappearing. “They fit on two 747s,” he said.

He hopes the exhibit will humanize Samaritans. “The truth is, there are good Samaritans. There are bad Samaritans. There are average Samaritans. There are smart Samaritans. There are less smart Samaritans,” he said.

“I like the people I study, and I want to give them a voice,” he added.

Across the National Mall from the Museum of the Bible, the Good Samaritan makes an unlikely appearance at the National Gallery of Art. The exhibit “The Double: Identity and Difference in Art since 1900” does not reference Samaritans, but independent scholar Hillel Schwartz’s essay in the exhibit catalog is all about Samaritans, whom he describes as an “Israelite double.”

In biblical times, Samaritans “were next-door neighbors to Judaeans but no kissing cousins,” he writes.

Schwartz, who is working on a book about emergency that will address the Good Samaritan, said sermons centering on the parable increased in the mid-18th century, when emergencies were first thought about in an institutionalized way in the West.

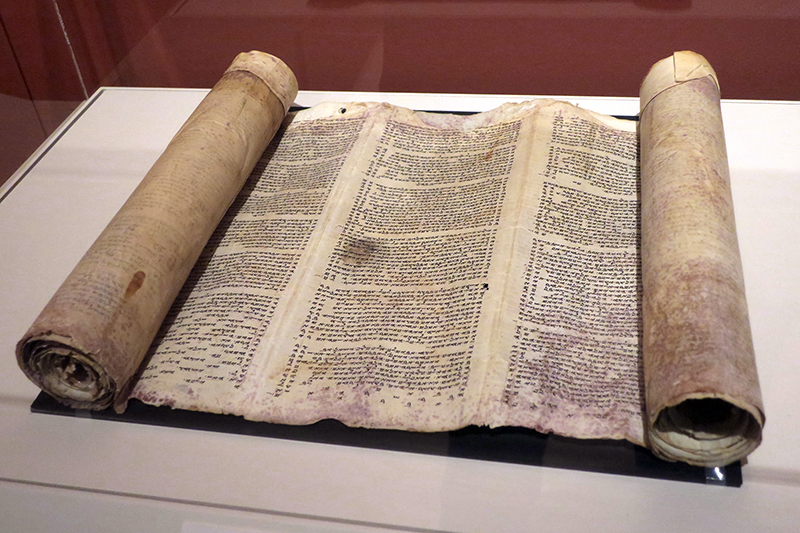

A Samaritan Torah scroll from Nablus, circa 1160. Photo by Menachem Wecker

In the current projects on Samaritans, Schwartz doesn’t see new archaeological or textual findings, and he thinks the Samaritan community has a long history of supporting projects that present it in a positive light. But, he said, it’s no coincidence there’s once again increased attention on Samaritans, noting new research on altruism that pushes back against social Darwinist and neo-liberal tendencies to view the world as every-man-for-himself.

“The fact that you would have more interest in Good Samaritans is significant in that cultural, historical moment,” he said. “It is one of the current paths toward projecting optimism into the future.”

In a recent talk to a church group, Fine noted the Good Samaritan is the guy who does not avert his eyes when someone is in need. Everyone wants to believe they’d do as he did, but, Fine told the group, everyone present would likely act not like the Samaritan, but as the priest and the Levite did and avert their gaze.

“Who has been on the subway and hasn’t?” he said.