(RNS) — As weather cools and the leaves change color, pagans around the country gather to observe the autumn equinox, a time of year when day and night are of equal length. The celebration, known by several names, including Harvest Home, Mabon or simply the equinox, is often described as the Pagan Thanksgiving.

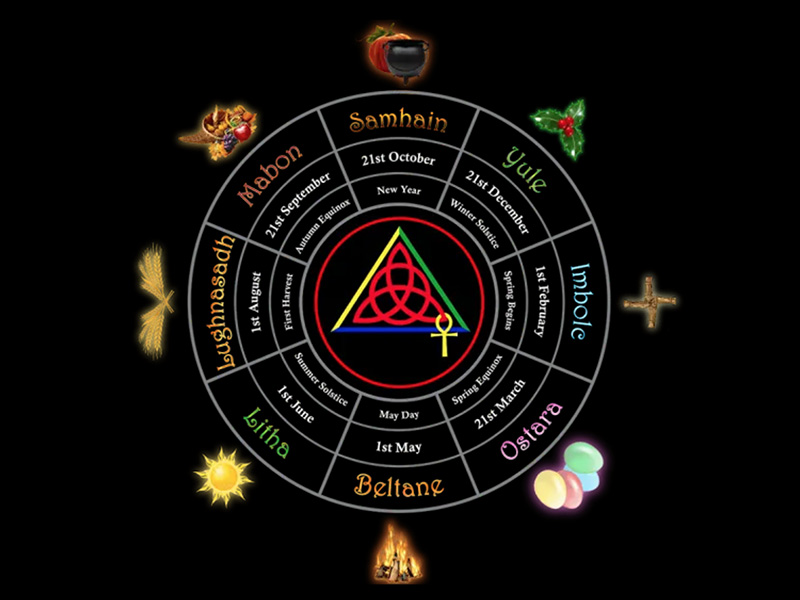

Mabon, as it is most commonly called, is the second of three harvest festivals on the Wheel of the Year, the pagan holiday calendar. Standing between August’s Lunasa and October’s Samhain, Mabon — celebrated this year on Thursday (Sept. 22) — marks the height of the harvest and the changing of the seasons.

While the Mabon, like the other seven sabbats on the Wheel, is informed by older agricultural practices, its name is not so old. As modern paganism was first developing through the 1960s, the sabbat was simply called the autumn equinox.

Then, in 1974, American witch Aidan Kelly claims to have given the holiday its name, along with two other sabbats: Litha and Ostara. In a 2017 blog post, Kelly said he named these three holidays while writing about the pagan calendar. While most of the other sabbats already had a Celtic name, these three did not. The mundane name “autumn equinox” offended his sensibilities, he wrote.

The Wheel of the Year, with eight sabbats. Image via the Cabot Kent Hermetic Temple

He began looking for a Saxon myth that was similar to the descent of Persephone in Greek mythology. At this time of the year, modern pagans often retell the story of Persephone, who descends into the underground for half the year, to represent the turning of the seasons. Kelly didn’t find a Saxon myth, but he did discover the story of Mabon.

As he recalls, Kelly renamed the holiday and submitted his new calendar to be published in The Green Egg, one of the first pagan magazines. The sabbat has been known as Mabon ever since.

But who is Mabon exactly? That is a question many pagans today have trouble answering, according to author and Welsh folk witch Mhara Starling.

“Mabon is a deity within Welsh mythology who is taken from his mother,” she said. His full name is Mabon ap Modron, which translates to “divine son of the divine mother.”

The god was taken from Modron at 3 days old and imprisoned for years in the walls of the castle at Caerloyw, as the story is told in the Mabinogi, the series of Welsh tales. He is found many years later by the hero Culhwch, who was on his own quest.

Starling identifies as a modern pagan polytheist, but she also studies and practices Welsh folk magic or swyngyfaredd, the art of enchantment. “The word that I use to describe myself in Welsh is swynwraig, which translates to ‘charmed woman,’” she explained.

She doesn’t seek to re-create the old ways, she said, but rather to honor them as part of her practice. During this time of year, she often has discussions about the name of the pagan sabbat.

Mhara Starling. Photo courtesy of Starling

Outside of Kelly’s usage, she said, Mabon, the god, has no connection to the autumn equinox. His story doesn’t even take place in the fall.

“Within Welsh traditions, the autumn equinox is a strange (holiday). We don’t have much on record of being celebrated in a pre-Christian manner here. But we do have a lot of reference to the farming traditions,” Starling said.

The Welsh communities, both historically and today, have celebrated the harvest with fairs and festivals, rather than religious events tied to the equinox. One such festival is Ffest y Wrach, which translates as “feast of the hag or witch.” It marks the end of the harvest and reaping of the final crops. Another festival, Caseg Fedi, translates as “mare of autumn” and honors the act of harvesting.

Diolchgarwch is a holiday that Starling remembers from her childhood. The word translates into “the giving of thanks” and is often celebrated in chapels as a way to honor the Christian God.

However, Mabon as a deity has never been tied to any of these festivals or rituals. If the ancient pre-Christian peoples of Wales did directly celebrate the equinox, it has yet to be discovered. Starling noted that little of Welsh culture was recorded before the Christian monks arrived.

While the name Mabon is now ubiquitous in the modern pagan world, some Welsh witches and Druids debate whether the name should be used at all. “It really doesn’t make sense to us,” Starling said.

“I’ve had a lot of discussions at moots and gatherings and rituals and such with various pagans, Druids, witches, who venerate the Welsh gods,” she said, “about how we don’t feel comfortable with (the equinox) being associated with Mabon.”

Most people who celebrate the holiday don’t even know who Mabon is, she added. She finds that to be true even in Wales, where pagans are often surprised to find out that he is even Welsh. “Some people will say they recognize it’s a Welsh word but didn’t know it was attached to a god,” she said.

Photo by Brad West/Unsplash/Creative Commons

Opinions on the matter range, but the general consensus among Welsh pagans today is for the holiday to evolve into a feast day honoring the god, she said. “It is the perfect opportunity to look more into Welsh mythology, but instead we have this faux mythology built around (the holiday),” she said.

One of Starling’s personal missions is to demonstrate just how much Welsh mythology has influenced modern paganism.

She pointed to the concept of “a year and day,” which was “the amount of time it took Cerridwen to prepare a potion,” she said. Today that time frame is used by covens for initiate study.

“The annual battle carried out by two divine entities features prominently in Welsh mythology,” Starling said. “This story seems rather similar to the core theme found in the battle between the Holly and the Oak king, which is central to many modern pagan traditions today.”

Cerridwen, Arianrhod, Rhiannon and Blodeuwedd — these are goddesses commonly honored in pagan circles and they are all Welsh.

“It would be nice if more people became aware of how much of modern paganism was influenced by Welsh mythology,” Starling said. This sabbat, named for a Welsh god, is a perfect time, she believes, to begin opening up that conversation.

Whether Mabon or autumn equinox or another name entirely, the sabbat is one that is bound by nature’s cyclical ebb and flow, and it joins many other similar harvest holidays held at this time. Modern pagans, at least those in the Northern Hemisphere, join others at this time in welcoming cooler temperatures, harvest foods and the coming together of community.