(RNS) — This summer, I learned — quite accidentally — that I’m a Highly Sensitive Person. I had never heard of such a thing. I was reading a book about another subject altogether, and the book mentioned this trait in passing.

Now, it’s not a big deal. Lots of people, I learned, are HSPs. Even so, upon reading more about it and taking the test, a great deal of my life suddenly made sense, even parts that I didn’t know could make more sense.

The people in my life have long made peace with my aversion to bright lights, synthetic material, and long trips away from home, for example. But what I now better understand is my constant feeling of being overwhelmed, especially over the past few years as my life has grown increasingly public in the midst of, and in part as a result of, ongoing controversies within my denominational and professional life.

I’m not in any of this alone, of course. The church at large and my denomination specifically are going through a reckoning unlike any that has taken place for generations, so it makes sense that many of us are distressed, disoriented or deconstructing.

Everywhere we turn — on social media, in the news, in our own families, among friends and in the church (especially in the church) — wounded people are crying out, voicing hurts and revealing pains that often have been carried and hidden for years.

This airing of wounds breaks longstanding, often unspoken, rules of an American culture characterized by a stoic stick-to-itiveness, one often translated by the church into a façade of happy-clappy, shiny people.

But, while I’m glad to see this new and brave vulnerability, bearing witness to these walking wounded brings wounds of its own — in the way a stone cast into the waters ripples out into eternity.

It hurts to see others hurt. It hurts to feel helpless, or worse, unwittingly complicit in another’s pain.

It hurts to see the long effects of abuse, of racism, of misogyny. It is painful to witness brothers and sisters fighting one another instead of serving, helping and loving one another. The polarization and division both in the church and out of it that we see played out in the news and on social media deliver fresh pain daily as the demonization of and by each side seems to ever intensify.

It’s hard at times not to despair.

My deepest desire on most days is simply to retreat. Yet, I can’t make myself not care. (Empathy is also linked to Highly Sensitive Persons.)

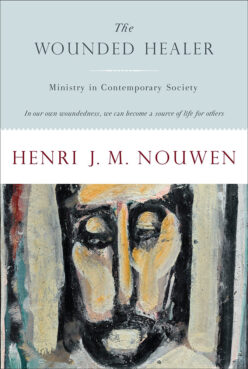

“The Wounded Healer” by Henri Nouwen. Courtesy image

A close friend recently urged me to read Henri Nouwen’s “The Wounded Healer,” which is celebrating its 50th anniversary this year and is now a classic work of Christian literature.

The phrase, “wounded healer,” was coined by psychologist Carl Jung to name an archetype going back to ancient Greek mythology, one that describes a would-be hero stymied by a debilitating (perhaps even self-inflicted) wound. This figure is echoed in later literary works from the Arthurian legends to T. S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land.” It is also understood to be a type of Christ because it is “by his wounds that we are healed.”

To be human is to be wounded, one way or another, Nouwen explains in his book, and some are called to minister through those wounds. The symbol of a wounded healer points to the truth that when we imitate Christ, our own wounds, too, have the power to help others heal. Or, as it is expressed on the cover of my edition of the book: “In our own woundedness, we can become a source of life for others.”

You don’t have to be in vocational ministry or in the healing profession to be a “wounded healer,” as Diana Raab notes in an article in “Psychology Today.” Raab offers some characteristics of those who might be one. She says you might be a wounded healer if:

- You are a lifelong seeker

- You have a strong sense of purpose

- People call on you when in need

- You’ve helped people since you were a child

- You look at all experiences as an opportunity for growth

- You’re able to find the calm in the chaos

And, of course, (perhaps it goes without saying), you are a wounded healer if you have scars of your own.

Such ministry cannot prevent suffering, of course. Such is not possible in our fallen human condition. But it can, Nouwen writes, “prevent people from suffering for the wrong reasons.” He explains, “When we become aware that we do not have to escape our pains, but that we can mobilize them into a common search for life, those very pains are transformed from expressions of despair into signs of hope.”

These words are a much-needed balm.

They also offer a gentle, necessary challenge.

The temptation amid so many revelations of harm — especially within the context of the church, which is supposed to be a place of refuge, safety and love — is retreat or denial or even counterattack.

But to have compassion — literally, to suffer with someone — is the opposite of this temptation. To have compassion is to share someone’s hurt.

A wound is, both literally and metaphorically, an opening.

To be open is to be vulnerable. And to be vulnerable with and for another is a gift.

It is also a kind of power, one that can be wielded in ways that further wound or in ways that help heal.

This power is expressed beautifully in a snippet a friend recently passed along that comes from a lesser-known work by Thornton Wilder called “The Angel That Troubled the Waters.” This mini-drama is set at a healing pool where those sick and in pain gather to await the daily stirring of the waters by an angel.

A newcomer to the pool, a physician, arrives, hoping to be healed of a “heart in pain.” But when the angel appears and prepares to stir the healing waters that day, the angel admonishes this impatient newcomer, “Draw back, physician, this moment is not for you.”

When the physician complains, saying he, too, is in need of healing, the angel tells him:

“Without your wound where would your power be? It is your very remorse that makes your low voice tremble into the hearts of men. The very angels themselves cannot persuade the wretched and blundering children on earth as can one human being broken on the wheels of living. In love’s service only the wounded soldiers can serve.”

In love’s service only the wounded soldiers can serve.

Many soldiers today, it seems, are wounded. Many, so many, have been broken on the wheels of living.

But love’s service needs them all.

In love, may they keep persevering.

May they — may we all — bear the power of these wounds like a gift.