Photo by Ksenia Yakovleva/Unsplash/Creative Commons

(RNS) — Reading the encyclopedia and watching public television as a kid, Linda Raedisch caught glimpses of “another Christmas” — one filled with ghosts and witches, where elves weren’t friendly toymakers tinkering in Santa’s workshop and the temperature wasn’t the only thing that was chilling.

“I like the scary and the sacred coming together at this dark time of year,” she said.

She wanted to know more, not only about the most frightening folklore of Christmases past, but also about the pagan and Christian origins of the traditions many still observe in the present.

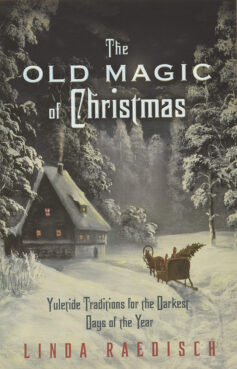

That’s what led Raedisch, who writes and lectures on all things arcane, to write the book “The Old Magic of Christmas: Yuletide Traditions for the Darkest Days of the Year.”

RELATED: Everything you didn’t know about Christmas

Several books and nearly a decade later, she said, “The Old Magic of Christmas” is “still the child of mine that everybody loves.” She still receives Christmas cards from readers with the holiday greetings scratched out and “Happy Solstice!” inscribed in their place, and learns of new and different things readers are finding in the book than she had in mind when she wrote it.

“The Old Magic of Christmas: Yuletide Traditions for the Darkest Days of the Year” by Linda Raedisch. Courtesy image

Christmas always has been a bit spooky, Raedisch said. In the biblical account of the Christmas story, she pointed out, angels share the news that Jesus has been born with the greeting, “Fear not!” which suggests a frightening appearance.

And ghost stories — best known from Charles Dickens’ classic story “A Christmas Carol” and referenced in that one line in the song “It’s the Most Wonderful Time of the Year” — were for many years a popular way to pass the time around the fire during long, cold winter nights.

“I think that we long for the sacred, but it frightens us also, and maybe Christmas is a way — just like Halloween is a way — of confronting the bad, scary stuff and making light of it,” she said.

It’s not just the scary and the sacred that mix and mingle during the Yuletide, Raedisch said, but also Christian and pagan traditions. While some debate whether Christmas trees and Santa Lucia’s crown of candles were introduced by Christians celebrating Christmas and various saints’ feasts or if they come from pagans celebrating Yule and the winter solstice, the author said she doesn’t like to single out traditions as belonging to one religion or another.

“I think it’s richer when it’s all all together,” she said.

Many of her readers are well-read witches and pagans, she said, but she hopes the book can bring everybody together for the holidays, including Christians and those, like her, who lean toward secular humanism and whose spiritual practices are “reading and writing.” Pagans and Christians alike can rediscover the “reason for the season” in the old stories and deepen their own beliefs.

Here are a few of the scary ghost stories of Christmases long, long ago that Raedisch conjures in “The Old Magic of Christmas.”

Elf lore

Clement Clarke Moore may have described Santa as a “jolly old elf” in his famous poem “A Visit From St. Nicholas” (the one that begins, “’Twas the night before Christmas … ”), but throughout folklore, elves are anything but.

For some people, elves were the spirits of ancestors. For others, they were former gods and goddesses, according to Raedisch, who writes more about elves in her book “The Lore of Old Elfland.”

Photo by Erin McKenna/Unsplash/Creative Commons

One Icelandic story, dating to a time after Christianity came to the country, suggests elves were some of the many children of Adam and Eve who weren’t bathed in time for a visit from God. Eve hid them; thus their reputation as “the hidden folk.”

In a way, the author said, “They were sort of their own tribe of people just on the other side of the veil, doing the same things that we do — even going to church.”

Not unlike Santa, elves also became a way of policing behavior, she said. A stranger in need of help could always turn out to be an elf. If one helped him, one might be rewarded; if not, one might be punished.

So one ought to, as the song says, be good, for goodness’ sake.

RELATED: Do humanists celebrate Christmas?

Werewolves and wise men

The Yuletide was also once inhabited — and still is, in some corners — by witches and werewolves and other creepy creatures.

Author Linda Raedisch. Courtesy photo

Some Christians who observe Advent, the liturgical season leading up to Christmas, treat it as a fast like Lent, the season leading up to Easter. Among the things included in that fast: sex. Which meant children born nine months later were suspect — they might be, of all things, werewolves, Raedisch said.

So might children born during the 12 days of Christmas, which was seen as a “risky” and “liminal” time, she added.

Some believed speaking of wolves during Christmas dinner might conjure them in Germany, according to the author. Failing to mention them might have the same effect in Lithuania.

But never fear, as Raedisch wrote in “The Old Magic of Christmas,” the beasts could be banished by the biblical wise men arriving to see the baby Jesus at Epiphany, celebrated at the end of those 12 days.

RELATED: Yule traditions new and old wish good riddance to 2020 at the winter solstice

Those tomten at Target

Also attached to the wise men is the story of the Italian witch Befana, who remains popular not only in Italy, but also around the world.

According to legend, Befana lived to regret turning down an invitation from the wise men to join them on their journey to see the baby Jesus, Raedisch said. The Christmas witch now drops toys down chimneys across Italy and beyond on the eve of Epiphany, still in search of the baby.

La Befana, the Italian Epiphany witch. Painting by James Lewicki, from “The Golden Book of Christmas Tales” 1956

Another creature who suddenly has become ubiquitous at Christmastime: Swedish tomten.

The small, Scandinavian household sprites look a bit like Santa himself with their pointed hats and long, white beards, according to the author. Perhaps that’s why they have become so popular, appearing on holiday decorations at Target and other major retailers.

Like Santa, tomten reward hard work with presents on Christmas. But they prefer porridge topped with butter to milk and cookies. And they’re believed to be the spirits of the ancestors who first established a homestead, she said.

Belief in tomten is ancient, according to Raedisch, but the mostly featureless figures, with just a nose peeking out from beneath their hats, “seem to be the mascots of Christmas 2022.”

RELATED: Italy’s Epiphany witch is a needed sign of pandemic-era hope (COMMENTARY)