(RNS) — While many still lament their diminished New Year’s celebrations, I take comfort in knowing that my childhood new year didn’t really start until Jan. 5. On that night, the eve of the Feast of the Epiphany, my siblings and I gathered around our kitchen table to fill a cup with wine and plate slices of panettone, the traditional sweet leavened cake of the season, for a special visitor.

As the majority of Catholics in our Bronx neighborhood were preparing to commemorate the Magi’s visit to baby Jesus, we children of Italian immigrants were also happily awaiting the arrival of La Befana — the witch.

In Italian folklore, Befana is a haggard old lady who streaks across the sky on her broomstick with a sack or hamper with gifts and good tidings for the year ahead. Well-behaved children are rewarded with sugary treats, naughty ones a stick or lump of coal. After coming down the chimney to deposit candy into empty bowls or stockings, Befana uses her broom to sweep away remnants of her sooty footprints and, most importantly, negative energy from the previous year.

Befana’s origins are colorful and varied: In the most common iteration, the three wise men encountered Befana en route to Bethlehem and asked her for directions. Though she couldn’t be of help, they invited her to join them on their journey anyway. Befana refused, citing too much housework. Later, she had a change of heart and rushed out to join them.

But it was too late. Befana now spends eternity on a quest for the Christ Child, stopping at every home on the way to deliver the gifts and blessings she otherwise would have left at the manger.

Another theory traces Befana to the goddess Strenia, the Roman deity of new beginnings honored at the start of each new year by the exchanging of gifts and sweet breads. Folklorists have also noted that “befana” may be an Italian mispronunciation of Epiphaneia, the Greek word meaning “appearance” or “manifestation.” Whatever her source, Befana is still alive and well today.

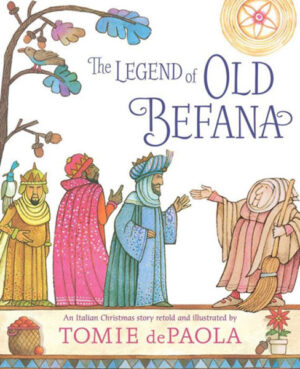

“The Legend of Old Befana” by Tomie dePaola. Courtesy image

A much beloved icon throughout Italy and a well-known figure to generations of Italian Americans, she is also recognizable to the scores of children who have enjoyed Tomie dePaola’s books “Strega Nona” and “The Legend of Old Befana.” As recently as 2018, an Italian-language film, “La Befana Vien di Notte,” depicted Befana as a 500-year-old woman disguised as a schoolteacher by day.

Though most often depicted with a stereotypical dirty face, hawkish nose, stringy hair, and a conical hat, Befana isn’t the least bit fearsome to those of us who know her. Her lopsided grin conveys warmth. Her eyes glow with the wisdom and compassion of a learned matriarch.

She was a caricature, but we knew that Befana possessed a singular and potent kind of magic. Like our mothers and grandmothers, she carried a great weight on her shoulders and accomplished a lot with very few resources.

When considering the tempest that was 2020, it might seem dubious to view the legend of Befana as spiritually and intellectually relevant. But that old Italian witch actually makes more sense to me today than she did when I was a kid.

There’s wonderful meaning in starting off the new year with a handful of candy and a broom. For me, it symbolizes the literal sweetness of having made it through to 2021, as well as the anticipation that the coming months will bring us that most elusive of feelings — hope.

Nor is Befana’s story one of missed opportunity. It’s a lesson in gentle tenacity: She didn’t become an esteemed legend by bemoaning her decision to eschew the Magi’s invitation. Instead, she set forth into uncharted territory and discovered that her own journey had both redefined and broadened her purpose.

If anything, the pandemic showed us that our seemingly secure and routine ways of living can disappear in the span of a few days. The last time I used a broomstick, for example, my husband and I were battling COVID-19 and I couldn’t sweep more than a quarter of the living room floor before quickly becoming exhausted and breathless.

This year, I’ll be reviving my celebration of La Befana. I’ll use that same broomstick to sweep away last year’s darkness and prepare my floors in anticipation of post-pandemic foot traffic. I’ll send sweet gifts to my family and friends. We’ll celebrate, debate and commiserate via FaceTime or Zoom.

Together or apart, frightened but ever optimistic, we might find that our willingness to persevere like Befana is its own epiphany.

(Antonio Pagliarulo is the author of two books on modern witchcraft, including “American Witch,” and five young adult novels. The view expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)