(RNS) — Not that there wasn’t a lot of other news last week, but I have found myself thinking about Frank Pavone, the crusading anti-abortion priest who was defrocked by the Vatican for disobedience and blasphemy. His case harks back to that of another crusading American priest, Leonard Feeney, a Jesuit disciplined by the Vatican disciplined for disobedience 70 years ago.

Feeney, whose story I once wrote up at some length, established himself as spiritual leader of a storefront ministry in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in the late 1940s. Located across the street from one of Harvard’s undergraduate residences, St. Benedict Center served not only as a gathering place for Catholic students but also as a missionary enterprise.

Feeney was a charismatic teacher and preacher, and he notched some impressive converts — impressive enough to stir up concern among the powers-that-were at nearby Harvard University. For his part, the Jesuit priest hated the school, blaming all the ills of the new atomic age on its secularism.

His message, delivered with satirical wit, was that whatever was not Catholic was to some degree anti-Catholic. What made him notorious was a hard-edged interpretation of the Latin dogma, extra ecclesiam nulla salus — no salvation outside the church.

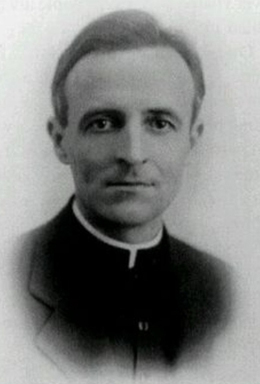

Leonard Feeney. Photo courtesy of Wikipedia/Creative Commons

Although pre-Vatican II American Catholicism was anything but a bastion of liberalism, the claim that no one other than actual members of the Catholic church could be saved was not what Feeney’s fellow Jesuits at Boston College taught. The genial archbishop of Boston, Richard Cushing, found Feeney’s take to be unacceptable community relations.

What to do?

Feeney was ordered to leave Cambridge and report for homiletics duty at the College of the Holy Cross in Worcester. When he steadfastly refused to go, he was, over a period of several years, deprived of his priestly faculties, kicked out of the Jesuit order and, in 1953, excommunicated. The “Boston Heresy Case” became frontpage news around the country.

Calling themselves the Slaves of the Immaculate Heart of Mary, Feeney and the followers who stuck with him took to assembling every Sunday on Boston Common to denounce his enemies: Protestants, Masons, Boston’s Catholic hierarchy and especially the Jews. In 1958, the group decamped to a farm in western Massachusetts. By the time of his death two decades later, Feeney was admitted back into the church — as were, in due course, most (but not all) of the other Slaves.

For many years, this episode has been dismissed much the same way the 1925 Scopes “Monkey Trial” used to be — as an eccentric reactionary moment in the steady adaptation of Christianity to the modern world. But like the resurgence of old-time evangelicalism, Feeney’s moment now looks less and less like what his biographer in 1965 called a “comic-opera heresy.” Indeed, in a forthcoming study, a Boston College historian, the Rev. Mark Massa, sees Feeney as the progenitor of a Catholic fundamentalism that is alive and kicking hard today.

Which brings us to Frank Pavone. The longtime head of the anti-abortion organization Priests for Life, Pavone, like Feeney, has not taken a position at odds with Catholic doctrine, which is clearly and undeniably opposed to abortion. But, like Feeney, he has accused church leaders of being soft on it.

Also (in line with his surname, Italian for peacock) Pavone is a preening zealot who has been at odds with his hierarchical superior, Amarillo Bishop Patrick Zurek, for years, in part because of Priests for Life’s lack of financial transparency.

In 2011, Zurek suspended Pavone from ministry outside Amarillo and barred him from appearing on the conservative Catholic TV network EWTN. In 2016, Zurek pronounced Priests for Life to be a civil institution.

Leonard Feeney speaking at St. Benedict Center, Cambridge, Mass.

It’s worth asking whether Pavone, who is still styling himself “Fr.” on the Priests for Life website, will, like Feeney, lead his organization into the kind of sectarianism that, as Massa defines it, is an essential mark of fundamentalist Catholicism. The best-known example of this is the Society of St. Pius X, an organization of traditionalist priests founded in the wake of Vatican II.

In Pavone’s case, the answer may turn on whether he ends up, like Feeney, excommunicated. According to the Rev. James Bretzke, a Jesuit moral theologian at John Carroll University in Cleveland, “If he persists in maintaining that he is a priest, and if he were to perform the sacraments, especially Mass, in a public way, then those could constitute crimes that could result in excommunication.”

Whatever the future holds, Pavone’s removal from the priesthood and the Vatican’s own declaration that Priests for Life “is not a Catholic organization” constitute an authoritative signal to the Catholic world. With one exception, no American bishop has risen to his defense. Many conservative Catholic voices have hit the mute button.

And yet, as was the case with Feeney, there is a penumbra of support for Pavone’s brand of Catholicism that will not go away — one with roots in the either-or theology of the Jansenists of the 17th and 18th centuries. “It is an approach to moral issues where you tend to feel that whatever is more rigorous is somehow better,” said Bretzke.

These days, this approach is embraced by the substantial number of American Catholics who disdain Pope Francis, an anti-Jansenist figure if there ever was one. Among them, Pavone is likely to remain a hero, even if they don’t say so out loud.