NEW YORK (RNS) — At the Islamic Cultural Center of New York on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, Sheikh Saad Jalloh, the center’s imam, reminds his congregation to be aware of the fact that at a busy mosque with more than 1,500 members in the middle of a major metropolitan area, anything can happen.

And anything often does: Jalloh said the center frequently receives bomb threats by phone and email. People have walked their dogs in the prayer room of the mosque and dumped garbage in the sheikh’s prayer station.

Security at the mosque involves both communication with the police — “We have a very good relationship with the 23rd Precinct,” said Jalloh — and vigilance from those who attend.

“I always give a brief talk right after the prayer to the congregants,” Jalloh told Religion News Service, encouraging them “to be very nice with the neighborhood, to treat them well, to make sure that there’s a good relationship between us and them, and not allow hatred, because this may lead to hate crimes or may lead to (an) attack.”

Imam Saad Jalloh, left, speaks during an event with New York City Major Bill de Blasio, right, at the Islamic Cultural Center of New York in Manhattan in 2019. Photo courtesy of ICCNY

New Yorkers of all faiths have faced increasingly daunting numbers of religiously motivated hate crime and bias incidents among the more than 450 confirmed bias and hate incidents reported in their city last year. These attacks range from the personal — two Sikh men were robbed and assaulted in April, their turbans ripped from their heads — to the institutional, as when a Catholic church received bomb threats last May after the draft of a Supreme Court opinion overturning Roe v. Wade was leaked.

In November alone, a Muslim woman was attacked on the subway and two men who made threats against Manhattan synagogues were arrested while carrying, among other weapons, a high-capacity magazine.

But official statistics, experts say, only begin to capture the dimensions of hate crime in New York.

“It’s important to say that the hate crime numbers are underreported,” said Hassan Naveed, executive director of the city’s Office for the Prevention of Hate Crimes. Some members of the city’s minority communities “may not necessarily have the same access or comfort level in calling 911 to file a complaint about a hate crime.”

Steam vents on a street in Manhattan, New York. Photo by Luke Stackpoole/Unsplash/Creative Commons

A recent survey, funded by the OPHC and conducted by the New York chapter of the Council on American-Islamic Relations, found that only 4% of respondents who experienced a hate crime reported it to the police.

Naveed’s office, launched in 2019, coordinates the city’s hate and bias discrimination response across several agencies, from the Department of Education to the Police Department. It also partners with local community groups, led by six anchor organizations focusing on education, community relations and law enforcement.

The anchor groups include the 67th Precinct Clergy Council, based in eastern Brooklyn, which calls itself the “God Squad”; the Arab American Association of New York; Asian American Federation; the Hispanic Federation; the Jewish Community Relations Council; and the New York City Gay and Lesbian Anti-Violence Project.

Through these groups, OPHC has helped Jewish organizations and synagogues in the city to bolster security and helped the Muslim Community Network to create its first hate crime prevention survey. With the Sikh Coalition, it organized a hate crime education event for taxi drivers at John F. Kennedy International Airport.

The office also facilitates workshops on how to apply for security grants and distributes information about reporting hate crimes in different languages to reach deeper into immigrant communities.

“We really have to figure out how to collectively as a society take everything we know and really shift the way we think,” said Naveed. “We are community building constantly. We also ask organizations to work with each other, to get to know each other, to learn from each other.”

Community building also takes place in neighborhoods directly between local police precincts and houses of worship. The NYPD has dedicated neighborhood coordination officers who work within specific precinct sectors, where they get to know the local schools, community leaders, houses of worship and clergy.

With a rash of antisemitic incidents in recent years, Jewish groups have organized additional lines of defense to improve security at Jewish community centers and synagogues around the city. For more than 15 years, the Community Security Service has partnered with law enforcement, local government and other Jewish organizations to train volunteers to protect New York’s Jewish institutions. Today, hundreds of CSS volunteers keep watch over synagogues and Jewish communal spaces in the city.

People attend a “No Hate No Fear” rally in New York in January 2020. The primary organizers of the event were the JCRC of New York, CSI and the UJA-Federation of New York. The rally took place in the aftermath of attacks against Jewish communities in Jersey City, New Jersey, and Monsey, New York. Community Security Service volunteers provided security on the ground. Photo courtesy of CSS

In the aftermath of the November 2022 Club Q shooting in Colorado, CSS came together with OPHC and LGBTQ Jewish organizations for security and situational awareness training sessions.

Evan Bernstein, CEO and national director of CSS, also believes in a community-building, community-wide approach. He is a co-founder of the Interfaith Security Council, which regularly brings together more than 20 NYC faith-based organizations to discuss best security practices and community concerns, share resources and promote interfaith dialogue.

“It’s harder sometimes to come together on political issues or religious issues,” said Bernstein, “but one common denominator is a lot of religious leaders and their congregations are feeling vulnerable religiously.”

The Interfaith Security Council was also co-founded by Rabbi Bob Kaplan, executive director of the Jewish Community Relations Council of New York’s Center for Community Leadership, and Pastor Gil Monrose, executive director of the New York City Office for Faith-Based and Community Partnerships. The OFCP works with houses of worship on solutions to gun violence, mental health concerns, affordable housing, food insecurity and security threats. Besides teaching security measures directly, the council facilitates trainings on security grant applications for different communities.

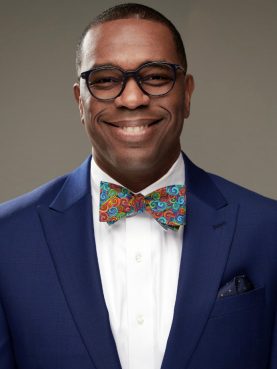

Pastor Gil Monrose. Courtesy photo

“Our office exists so that all faith groups are represented in terms of city government, and also to be able to share the resources that our city provides to all faith communities, to help them navigate the complexities of the city of New York. Our work is to be that bridge between the city and our faith leaders and faith communities,” said Monrose.

On the day Monrose spoke to RNS, he attended a call between houses of worship and the NYPD that served as an opportunity for faith communities to express any concerns and for law enforcement to check in on security.

“We work better in groups in terms of doing as opposed to standing alone,” said Monrose “So when one person or group is doing something, we are all doing it.”

With thousands of faith communities in the city of New York, Monrose said, security for its houses of worship depends on collaboration and mutual concern.

“Every day there are people who wake up thinking about how we keep our community safe. That is our challenge,” said Monrose. “To make sure that we are providing the resources and really looking at the dangers we face collectively, and that we are able to tackle them head on for everyone.”