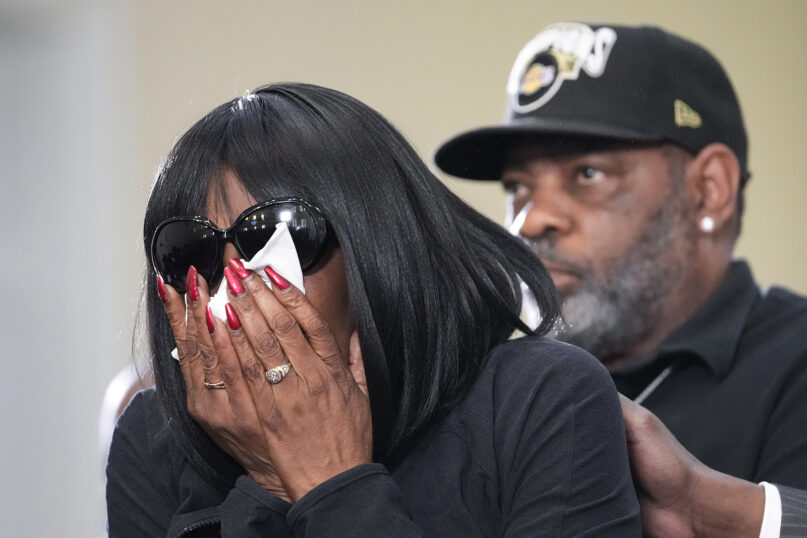

(RNS) — In an increasingly familiar scene, the parents, spouses or siblings of the victims of high-profile lynchings appear on national television, demanding justice in the days after a loved one’s death. The latest is RowVaughn Wells, whose son Tyre Nichols died after being beaten by five Memphis, Tennessee, police officers, heartbreakingly discussing her trauma in countless media interviews while still processing the brutal killing.

It’s unforgiving Catch-22: The media often plays a pivotal role in forcing police departments to own up to the crimes their officers have committed. Without media coverage, the families’ hopes for accountability will diminish. I understand too that without media coverage, justice can feel like an illusion. But the exposure undoubtedly takes an enormous toll, on fathers, families, friends and especially on Black mothers.

When a loved one dies, small tasks become monumental. Showering can be difficult. Getting dressed can feel like a burden. Preparing to view the body and plan funeral services can feel like a waking nightmare. Communicating with loved ones can be hard, much less with strangers. Preparing to face the media, nerve-wracking at the best of times, must be torturous for mothers freshly mourning their children. Retelling the story of what happened to their beloved must be gut-wrenching, and possibly damaging to their well-being.

Consider Amber Carr. In 2019, a police officer shot and killed Carr’s sister, Atatiana Jefferson, in Jefferson’s home in Fort Worth, Texas. Carr, whose son was with Jefferson the night she was killed, advocated for justice for her sister. Not long after Jefferson’s death, the sisters’ father died. Now, less than four years after Atatiana’s killing, Carr has died at the age of 33.

Erica Garner‘s father, Eric Garner, died in July 2014 after a police officer placed him in a chokehold. His cries of “I can’t breathe” shocked a nation and became a rallying cry for police reform. After her father’s passing, Erica Garner became an advocate for police reform. She died at 27 from cardiac arrest.

Society is constantly asking Black women to be strong, to share their agony and grief while others look on, filled with disbelief and shock.

If this were the only burden society put on Black women, it would be cause for outrage, but Black women deal with so much more. In a February 2021 paper, “Health Equity Among Black Women in the United States,” published in the Journal of Women’s Health, the authors, Juanita J. Chinn, Iman K. Martin and Nicole Redmond, explain that Black women suffer from a host of ills brought on by their environments, including a medical community that ignores them:

Black women are disproportionately burdened by chronic conditions, such as anemia, cardiovascular disease (CVD), and obesity. Health outcomes do not occur independent of the social conditions in which they exist. The higher burden of these chronic conditions reflects the structural inequities within and outside the health system that Black women experience throughout the life course and contributes to the current crisis of maternal morbidity and mortality.

We should ask ourselves how often Black women can be put in this position. Most importantly, we must address the underlying conditions that allow police in jurisdiction after jurisdiction to murder Black people. But as Wells grieves her son’s untimely death by lynching and other mothers do the same, we need to see past the media ritual, past even a Black mother’s strength, to appreciate the sacrifice required simply to get out of bed.

Jennifer R. Farmer. Courtesy photo

I hope we can do so not just for the Black mothers we see on television, but for the Black mothers in our lives and communities.

(Jennifer R. Farmer is the author of “First and Only: What Black Women Say About Thriving at Work and in Life.” The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)