(RNS) — Sans apps and online calendars, tracking Easter is no simple task.

Unlike many fixed annual holidays, Easter — which falls on the first Sunday after the first full moon following the spring equinox — can be anytime between March 22 and April 25 or, for Orthodox Christians who use the Julian calendar, between April 4 and May 8. In the Middle Ages, an entire science called “computus” was developed to pin down Easter’s highly variable date.

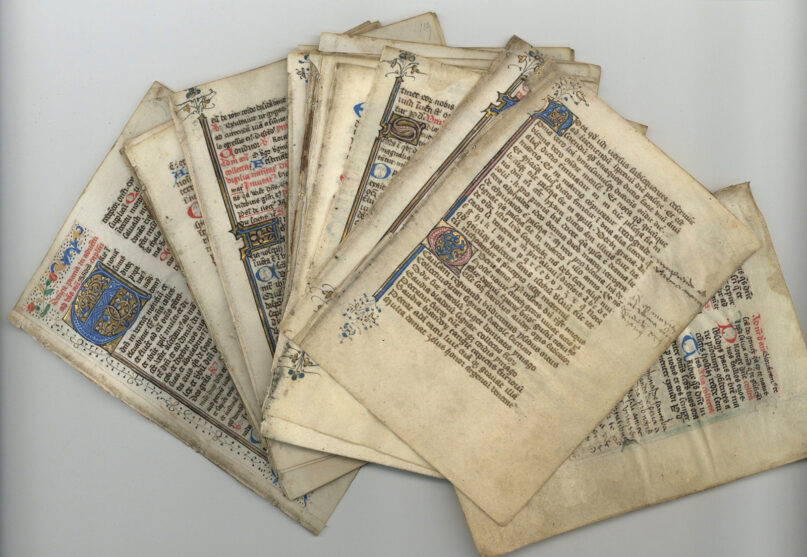

On Monday, The Raab Collection, an antiquities dealer in Ardmore, Pennsylvania, near Philadelphia, put up for sale a rare 15th-century manuscript containing a cipher that, when decoded, helped calculate the date of Easter during that period.

“Finding something with such a clear connection to our modern lives, finding this rare, direct connection via this computus text, is not something one sees every day on the market,” Nathan Raab, principal at The Raab Collection and author of “The Hunt for History,” told Religion News Service.

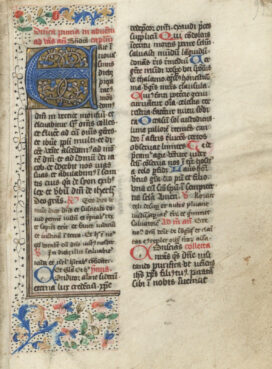

The medieval manuscript, which The Raab Collection is selling for $16,500, contains 25 double sided folios, or pages, handwritten in Latin, illustrated in pink and blue and illuminated in gold. Based on the text, coloring and decorative elements, experts believe it originated in or around Belgium, according to Raab.

Katie Bugyis. Courtesy photo

The Raab Collection believes the pages are part of a larger liturgical book, called a breviary, that was commissioned by a clergyman in the early 15th century. Katie Bugyis, a faculty fellow of the Medieval Institute at Indiana’s University of Notre Dame, told RNS breviaries were used by clerics and members of monastic communities for the performance of the Divine Office, a set of prayers that occur at set times each day.

“Just as it was important for monks and nuns, it was also important for clerics to maintain their own sort of private devotions,” said Bugyis. “And they did that by observing the hours. A breviary would have supplied all of the chants, prayers and readings that he would have needed to observe those hours of prayer.”

This manuscript also includes, in full or in part, the Litany of the Saints, Psalms 132 and 118 and at least one hymn.

According to Bugyis, during this period Easter would have been the pinnacle of the liturgical year and perhaps one of the few times when parishioners attended Mass and received the Eucharist. Knowing the date of Easter was critical not only because of the holiday’s significance, but also because, as Máirín MacCarron, a lecturer at the University College Cork, in Cork, Ireland, told RNS, “it affects about one-third of the liturgical year.” Ash Wednesday, Lent and Pentecost, for instance, all revolve around Easter.

“That’s why having a computus text like the one that we find in the breviary is so important,” observed Bugyis. “It was really complicated, trying to figure out the lunar cycle in any given year, and when the moon is waxing and waning.”

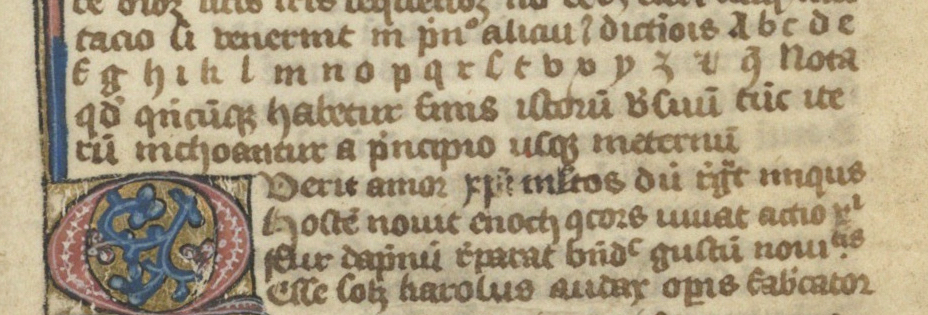

A detailed view of the 15th-century manuscript for sale. Photo courtesy of The Raab Collection

In this manuscript, the cipher takes the form of a mnemonic poem, an accompanying alphabet and a description of the calculation process.

“The letters would have directed the reader to a feature of the calendar matched to a particular year or month. The poem under it would have helped the reader remember how to use the cipher,” Raab explained via email. He added that this cipher is rare and requires a specialist to interpret it.

Beyond the cipher, the manuscript’s rich decorations and the handwriting in the margins indicate it would have been costly to produce and continued to be used over the years, according to Bugyis.

“This was someone that had some means to be able to have a manuscript like this produced for him, and suggests maybe he was associated with a cathedral that had some means, or maybe he had a patron, or maybe he came from a wealthier family himself and had independent means.”

A page of the medieval manuscript. Photo courtesy of The Raab Collection

Raab said the manuscript came from a private collection, and he added that he couldn’t predict where it could end up. The Raab Collection’s typical buyers include everyone from private collectors to major institutions. Regardless of who purchases it, Raab said the manuscript provides “unique insight into how religion was such an essential part of most people’s lives back then in a way that today might be hard for us to understand.”

In a technology-saturated era, most people don’t pause to consider why the timing of Easter seems so erratic year to year. But, said MacCarron, who authored “Bede and Time: Computus, Theology and History in the Early Medieval World,” computus texts like this one remind us that the dating of Easter isn’t random. It’s a calculation that’s deeply symbolic and has cosmic resonance.

“Easter happens at the first Sunday after the first full moon after the equinox, at the time that light is winning over darkness. Because that’s what Easter is,” she said. “So there’s all this cosmic symbolism in Christianity that, as modernists who live in this electrified age, we miss. We completely miss all this.”