(RNS) — On Tuesday (April 18), the Supreme Court heard oral arguments in this year’s big religion case, about an attempt to get the court to expand employers’ legal obligation to accommodate the religious needs of their employees.

The case, Groff v. DeJoy, concerns Gerald Groff, an evangelical Christian mail carrier at a small Pennsylvania post office who refused to work Sundays delivering Amazon packages, per the U.S. Postal Service’s deal with the online retailer. Because Groff’s refusal led to extra work for his fellow postal workers, one resigned, another transferred and a third filed a grievance.

After being disciplined, Groff himself resigned and filed suit under Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, which requires employers “to reasonably accommodate to an employee’s or prospective employee’s religious observance or practice without undue hardship on the conduct of the employer’s business.” Represented by the First Liberty Institute, a conservative Christian firm based in Plano, Texas, he’s asking the court to overturn Trans World Airlines v. Hardison, the 1977 precedent that defines “undue hardship” as anything that would require more than a “de minimis” (minimal) cost, including the cost of burdening fellow employees.

That Groff’s employer was the U.S. Postal Service is historically resonant, since it was Sunday mail service that caused our first national uproar over church-state separation. As they say, the postman always rings twice.

In 1810, Congress passed a law requiring post offices to stay open for mail transport every day of the week. Amid the religious upsurge known as the Second Great Awakening, prominent Protestants were outraged at this violation of the Lord’s Day.

Their efforts to reverse the law culminated in 1828, when Lyman Beecher, the big cheese in New England Congregationalism, and an evangelical merchant from Rochester, New York, named Josiah Bissell Jr. spearheaded the creation of the General Union for the Promotion of the Christian Sabbath.

Mobilizing religious merchants, Bissell had the organization circulate more than 100,000 copies of a talk he’d given attacking Sunday mail. In addition to boycotting transportation companies, the group aimed 900 petitions, some with thousands of signatures, protesting Sunday mail service at Congress, where they landed on the desk of Kentucky’s Richard M. Johnson, chairman of the Senate post office committee.

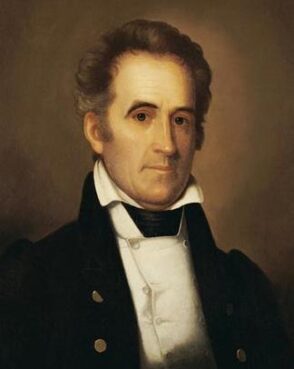

Portrait of Sen. Richard M. Johnson of Kentucky, by Rembrandt Peale. Image courtesy of Wikipedia/Creative Commons

A hero of the Indian wars and the kind of old-time Baptist who believed in keeping church and state as far apart as possible, Johnson gave the efforts a thumbs-down. In his committee report, he pointed out that not all Americans consider Sunday to be their day of rest and religious devotion, and that included some pious Christian denominations as well as the Jews.

Those petitioning for discontinuance of mail transportation on Sunday “appear to be actuated by zeal,” he wrote, “but they assume a position better suited to an ecclesiastical than to a civil institution.” Congress was “not the proper tribunal to determine what are the laws of God”; moreover, it was prohibited by the Constitution from favoring one religious group over another.

And so the Senate committee declined to advance a bill and the postal service continued to do its business on all days of the week. Until 1912, that is, when there arose a Congress that knew not Johnson — and which without debate passed a law calling a halt to Sunday mail delivery.

To be sure, Groff v. DeJoy does not challenge the postal service’s contract to do Amazon’s Sunday business — presumably to the sorrow of Beecher and Bissell, wherever they may be. In seeking to bend employers to the spiritual wants of employees, the suit is backed not only by conservative Christian groups but by organizations representing such non-Christian minorities as Hindus, Muslims, Orthodox Jews and Sikhs, whose interest in promoting Sunday sabbath observance is, one presumes, less than minimal.

At oral argument, however, even some members of the conservative supermajority who in the past have pushed the envelope on Christian free exercise (i.e., Chief Justice John Roberts and Justices Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh) seemed unwilling to do more than modestly raise the “de minimis” hurdle. As the headline on Amy Howe’s Scotusblog analysis announced, “Justices look for common ground in postal worker’s religious liberty case.”

Whether Sen. Johnson today would go along with having the U.S. government force all employers, private and public, to significantly underwrite their employees’ religious practices is hard to say. I’m inclined to think he’d draw a pretty sharp line, if not at “de minimis” then at the issue of burdening fellow employees.

How is it not an undue hardship to require an employee to work overtime so that a fellow employee can engage in religious observances that may be antipathetic to her own?

Whatever the case, we know how Johnson viewed campaigns like that waged by the General Union for the Promotion of the Christian Sabbath.

“Extensive religious combinations, to effect a political object, are, in the opinion of the committee, always dangerous,” he wrote. “All religious despotism commences by combination and influence; and when that influence begins to operate upon the political institutions of a country the civil power soon bends under it; and the catastrophe of other nations furnishes an awful warning of the consequence.”

Can somebody shout Amen?