(RNS) — In March, Nadia Kahf, a family law attorney from Passaic County, New Jersey, made headlines as “the first hijab-wearing Muslim woman” to serve as a state Superior Court judge in the United States. A day later, Dalya Youssef, a family law attorney who also wears the Islamic headscarf, was sworn in to the Superior Court bench in Somerset County, New Jersey.

These local news stories are no doubt intended as celebrations of growing diversity on the bench, and the headlines make sense insofar as women who wear the hijab are much more likely to experience labor market and workplace discrimination in the U.S. than women who don’t.

But the news media’s coverage of Muslim women’s “firsts,” whether as jurists or in other public roles, feeds the sense that their contributions arise chiefly from their sartorial religious practice. The headline on a recent story about Kahf in the North Jersey Journal captured the problem well: “She’s the first judge to wear a hijab on the bench in NJ. It’s not her only accomplishment.”

Beyond distracting from Muslim women’s achievements, the focus on the hijab invites those who object to their faith and their gender to share their bigoted reactions.

The fact is, we’ve passed the point where a female Muslim judge is an oddity. In New Jersey alone, Sharifa Salaam and Kalimah Ahmad, albeit not-hijab-wearing, serve as Superior Court judges in Essex and Hudson counties, respectively.

Carolyn Walker-Diallo, left, uses a Quran during to be sworn in as a New York civil judge in 2015. Video screen grab

Contrary to some headlines, Kahf will not even be the United States’ first hijabi judge. That distinction likely goes to Carolyn Walker-Diallo, an African American Muslim woman who was sworn in as a New York civil judge in 2015 and subsequently elected a New York Supreme Court 2nd Judicial District judge in 2021. In June of last year, Laila Ikram, who wears hijab, was sworn in as a judge pro tempore in Arizona.

When Walker-Diallo was sworn in, her elevation to the bench prompted criticism on conservative social media, particularly her choice to swear allegiance to the U.S. Constitution with her hand on the Quran, with some commenters implying that use of the Quran in such settings means that “Muslims are trying to take over this country.” (For the record, although the Bible has been commonly associated with official swearing-in ceremonies, there’s no requirement to use a religious text to administer the oath, much less the Bible.)

At the time, unfounded fears of religious Muslims in public service were common, finding expression in so-called anti-Shariah laws in which states forbade “the application of foreign laws” in their courts. By 2017, 14 states had enacted such laws, whose only impact was to stir up and legalize bigotry against Muslims and Islam.

Constitutionally, such laws are irrelevant, as no religious tradition can form the basis of laws, be it Shariah or canon law. But the anti-Shariah trend had its intended effect: tainting Muslim Americans’ involvement in U.S. jurisprudence. Indeed, after the Supreme Court opinion in the Dobbs case last summer, even liberal pundits compared the reversal of Roe v. Wade to Shariah, implying that limiting of reproductive rights is un-American — no matter that it was U.S. evangelical Christians who had lobbied for decades to overturn Roe.

Perhaps surprisingly, backlash to Kahf’s nomination has even come from conservative corners of the Muslim community. Last month, Yasmine Mohammed, founder of the Free Hearts Free Minds foundation, reported that some Muslims had criticized Kahf for participating in a system of law other than Shariah. Others claimed women are not allowed to be judges in Islam.

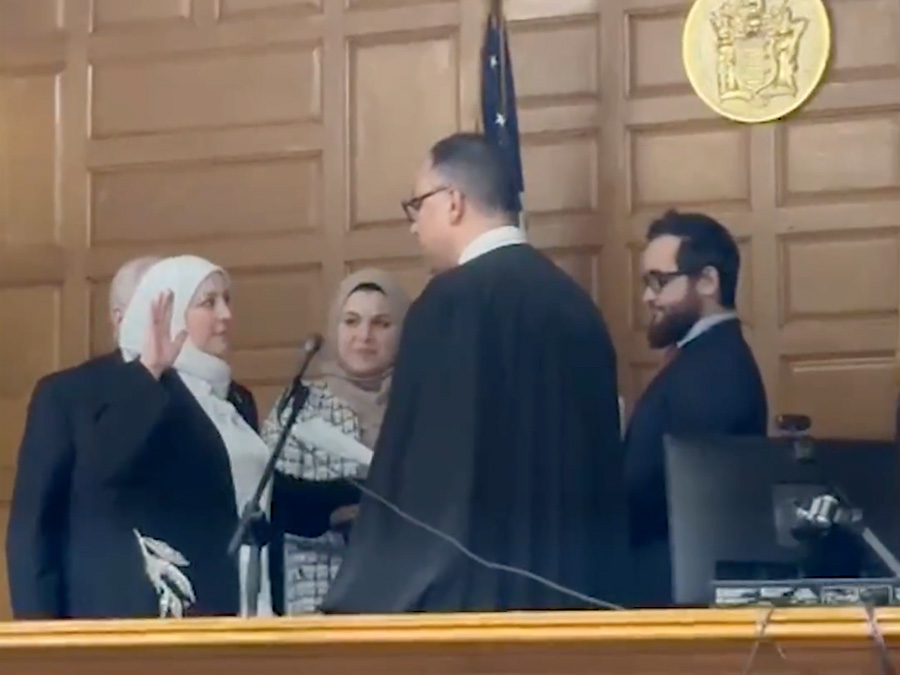

Nadia Kahf, left, takes an oath on March 21, 2023, in New Jersey. Video screen grab

In fact, there is no consensus on the topic among Islamic jurists, and any prohibitions formulated in the early Islamic period would have applied to judges who functioned before the religious-secular distinction was invented. It is debatable whether they would apply to a secular judge like Kahf.

Indeed, many Muslims supported Kahf’s nomination. The New Jersey chapter of the Council on American-Islamic Relations (of which Kahf is a former chairperson) was instrumental in garnering support for her candidacy in the face of nomination delays allegedly caused by Republican state Sen. Kristin Corrado. Kahf’s swearing-in ceremony was enthusiastically reported on by news outlets in Morocco, Kashmir, Turkey and the U.K.

It’s true that xenophobia has made Kahf’s and all the others’ rise all the more remarkable, even as it exposes the fissures in our body politic over who ought to have power. But journalists need to consider how to have this discussion without fueling a vicious cycle.

In a country where Muslim women are portrayed in the media as inherently foreign, voiceless victims or religious extremists, it is time to focus on qualifications and abandon outdated ideas of what a judge may look like. If we talk about a Muslim judge’s faith or her gender, let’s talk about how these attributes inform her views in a way that is productive for her public service.

(Anna Piela, a visiting scholar in religious studies and gender at Northwestern University, is the author of “Wearing the Niqab: Muslim Women in the U.K. and the U.S.” The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)