(RNS) — On July 16, 1945, in the desert 210 miles south of Los Alamos, New Mexico, a nuclear weapon was tested for the first time.

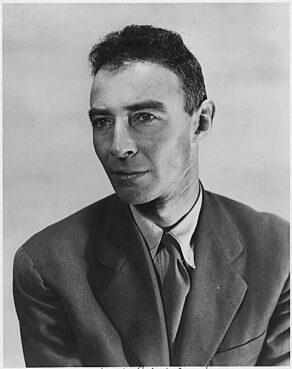

Recalling the scene 20 years later, J. Robert Oppenheimer, known as the “father of the atomic bomb,” uttered words he would henceforth be known for. Pale and emaciated for his 61 years, eyes gaunt, the physicist persistently avoided the camera as he spoke with emotionally subdued precision:

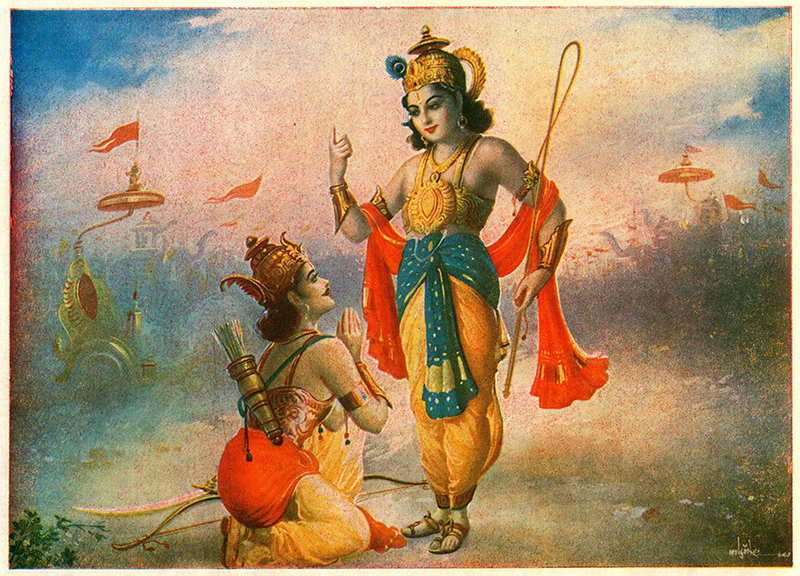

We knew the world would not be the same. A few people laughed, a few people cried, most people were silent. I remembered the line from the Hindu scripture, the Bhagavad Gita. Vishnu is trying to persuade the prince that he should do his duty and, to impress him, takes on his multi-armed form and says, ‘Now I am become death, the destroyer of worlds.’ I suppose we all thought that, one way or another.

At the time, only a small number of Americans knew much about the Scripture Oppenheimer quoted, though his hauntingly poignant delivery gave his recitation a special weight. The true impact its spiritual source had on Oppenheimer, however, and on the development of atomic weaponry remained largely unknown.

According to James A. Hijiya, author of “The Gita of J. Robert Oppenheimer,” Oppenheimer’s interest in ancient Indian philosophy grew out of a rebellion against his own upbringing. Of Jewish descent, his family was affiliated with Felix Adler’s Society for Ethical Culture and sent young Oppenheimer to the society’s school in New York, where his father was on the board of directors.

Abandoning religion’s spiritual and supernatural aspects, the school taught the importance of human welfare based on a foundation of secular moral principles. It also provided excellent training in the sciences and classics, but Isidor Isaac Rabi, a physicist who met the young Oppenheimer in 1929, before working with him later on the Manhattan Project, said Oppenheimer was already seeking “a more profound approach to human relations and man’s place in the universe.” He appeared to have found this approach in the Hindu classics, which seemed to interest him even more than physics.

In 1933, while he was teaching at Berkeley, his interest apparently reached new depths when he met Arthur W. Ryder, a professor of Sanskrit who taught Oppenheimer the language. Especially captivated by the Gita, Oppenheimer called it “the most beautiful philosophical song existing in any known tongue.”

J. Robert Oppenheimer, atomic physicist and head of the Manhattan Project, circa 1944. Photo courtesy of the National Archives catalog

Always keeping a well-worn copy of it near his desk, he gave the book to friends and regularly quoted passages, once at a memorial service for President Franklin D. Roosevelt. When asked by Christian Century magazine in 1963 to name the top 10 books that shaped his “vocational attitude” and “philosophy of life,” Oppenheimer listed the Gita, along with Shakespeare’s “Hamlet” and T.S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land.”

A 700-verse dialogue between an ancient warrior named Arjuna and his cousin Krishna (a form of Vishnu), the Bhagavad Gita is set on a battlefield at the edge of war.

Hoping to install his eldest brother, Yudhishthira, as ruler of a kingdom that has been usurped by their cousin Duryodhana, Arjuna is torn. Faced with the prospect of fighting an army filled with his friends and relatives, he despondently turns to Lord Krishna and asks if the throne is worth the price of slaying so many of his loved ones. Motivated by envy, Duryodhana might be in the wrong, but surely his crime doesn’t justify fratricidal bloodshed. Casting his weapons aside, Arjuna falls to the ground, overwhelmed with grief.

From a spiritual perspective, the peaceful solution feels like the obvious one, especially considering the stakes. Yet Krishna, who eventually reveals himself to be a manifestation of the divine, actually chastises Arjuna, albeit lovingly.

As a warrior, Krishna argues, Arjuna’s dharma, or sacred duty, is to fight, no matter what the outcome. While in life we can’t control the result of our actions, we can control our actions, and our best-performed actions are the ones most aligned with our nature. Just as the heart best serves itself and the body by performing its function of pumping blood, Arjuna best serves himself and society by performing his function as a warrior in the face of battle.

For him, the pacifist’s route — a route that isn’t his but that of a renunciate — isn’t selfless but the opposite, an action based on his own desire. If everyone discharged the duties of others instead of their own, the world would fall into disarray. Faith in the higher cosmic order dictates that all beings execute their responsibilities, even when doing so causes unhappiness or distress.

Inspired by these words, Arjuna asks Krishna to exhibit his cosmic identity, as a way of strengthening faith in the order he’s referring to. Pleased by his cousin’s change of heart, Krishna assents to the request and manifests a bewildering display of wondrous, brilliant and unlimited visions.

It’s at this moment, as an unfathomable radiance blazes from an incomprehensible form containing all that has ever existed, Krishna says the famous line, describing himself as the “destroyer of worlds” — not to instill fear, but to emphasize that ultimate destiny was out of Arjuna’s hands.

Gathering his senses, Arjuna prepares for battle, fulfilling his role to provide a providential end that has already been set in motion.

Understanding Oppenheimer’s quote in broader context, you can see how he, who had his own considerations of pacifism, might have quelled his doubts through the model of Arjuna. As Hijiya thoroughly conveys, the scientist very much determined his duties by his profession as a nuclear physicist, and made various statements in the course of making the bomb, as well as in the years after, touting the importance of following these duties.

In 1945, he told his peers at Los Alamos, “If you are a scientist, you cannot stop such a thing. … If you are a scientist you believe … that it is good to turn over to mankind at large the greatest possible power to control the world and to deal with it according to its lights and values.” Going further, in a magazine article published during the same period, remarking on whether it was good to give the world increased power, he said, “Because we are scientists, we must say an unalterable yes.”

If it was his duty as a scientist to help create the bomb, he believed it was the duty of the country’s political leaders to decide what to do with it. When fellow Manhattan Project scientist Leo Szilard wanted to circulate a petition cautioning President Harry Truman against dropping the weapon on a Japanese city, Oppenheimer forbade it, saying the country’s statesmen had information the scientists did not possess and were therefore the most qualified to determine its proper use.

Fate, Oppenheimer clearly surmised, was out of their hands. All they could do was play their parts to the best of their abilities, and allow others to play theirs.

Despite his distaste for the violence and suffering the bombs caused, and despite his criticism toward furthering the nuclear arms program after the war ended, it should come as no surprise that in his final years, Oppenheimer said that if he could go back in time, he would do things the same way.

His lack of regret shouldn’t be mistaken for a willful hardening of his heart. The footage of him reciting the line from the Gita makes it painfully clear that the bomb’s success brought him no joy. Like Arjuna, he carried out the obligations of someone in his position, surrendering to a destiny beyond his own comprehension.

(Syama Allard is a content writer for the Hindu American Foundation, based in Florida. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)