BANGKOK (RNS) — Street shrines are everywhere in Thailand’s capital, perched on pedestals outside homes, stores and even hotels, and they are more than decoration: Passersby frequently stop to light incense or simply bow to the image of Buddha or another deity inside the small, temple-like structures. Adding to the sense of near-constant devotion are the Buddhist monks who walk the streets, ready to accept donations of food. Filling a monk’s alms bowl is a way for lay Buddhists to earn merit.

Buddhism, which first arrived in the country about 1,000 years ago, is also a commercial boon for Bangkok, bringing Westerners flocking to the city’s many meditation centers and temples.

But some in Thailand have become concerned that the faith known for promoting its practitioners’ inner peace pays too little attention to the suffering of those around them.

A devotee receives a blessing after offering alms to a Buddhist monk on a sidewalk in Bangkok, Thailand, Tuesday, March 17, 2020. (AP Photo/Gemunu Amarasinghe)

The late Vietnamese Zen master Thích Nhất Hạnh coined the concept of “engaged Buddhism,” during the Vietnam War, when he extended his practice as a monk to include reducing the deprivation the war visited on the Vietnamese people. Among those he ordained into this way of practicing Buddhism is Sulak Sivaraksa, who later founded the International Network of Engaged Buddhists. Sivaraksa believes Buddhism needs to look beyond personal practice to bring social change. “Only meditating, that’s not Buddhism. It’s escapism,” he told journalists visiting INEB’s Bangkok office recently.

The movement is growing in response to religious conflict in Thailand. Religious violence has broken out in the country’s far south where the Muslim population is concentrated, and where ultranationalist monks are spreading hate. According to Suchart Setthamalinee, Thailand’s national human rights commissioner, misinformation is spread through temples stoking fears that Muslims plan to take over the country. In some areas, “Protect Buddhism” organizations have emerged.

But socially engaged Buddhists are addressing social justice issues within the faith as well. Buddhism has been unwelcoming toward women and transgender people: Some temples in northern Thailand have signs that say women are not allowed to enter the ordination hall area because of menstruation, and Bhikuni, or female monks, are not accepted in the order.

INEB has recently been advocating for transgender rights and the ordination of women. The group has also become involved in building environmentally friendly temples and raised awareness about forest degradation, which is both an environmental and a human rights issue in Thailand, where so-called forest dependent people have been forced off their lands.

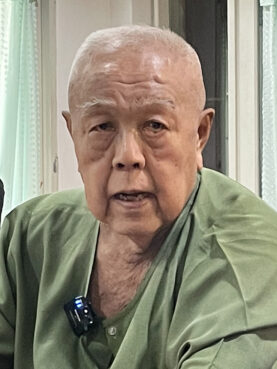

Sulak Sivaraksa in March 2023. Photo by Kalpana Jain

The group has made a particular impact with a ritual called “tree ordination,” which involves tying a saffron robe typically worn by Theravada monks around trees to stop logging. Depending on the community they are working with, socially engaged Buddhists may put a Christian cross or other religious symbol on the tree. The practice has been adopted by the Thai government and has spread to the United States, where activists most recently used it to protest a proposed $90 million training center for police and firefighters in Atlanta.

According to Sivaraksa, socially engaged Buddhism speaks to the Buddha’s teaching of “Kalyanamitra,” or “noble friendship,” which, the monk explained, is not just about speaking generous words, but telling the truth. Historically, said Andrew Alan Johnson, a scholar who spent several years in Thailand, Thai Buddhism has offered role models for questioning authority, such as Somdej Toh, an 18th-century monk who challenged royal authority based on Buddhist ideals.

Traditionally, too, Thai Buddhist temples tended to their local communities, providing health care, schooling and other services, and local communities took care of the needs of the monks. But in 1902, sweeping political changes instilled a centralized structure on the faith, not unlike that of the Catholic Church. Monasteries were consolidated under a hierarchical body known as the Sangha Council, led by a supreme patriarch who came to be appointed by the king. Local temples were no longer accountable to their communities.

In the ensuing decades, any criticism of the monarchy was punished harshly. In 1976, after students occupied Bangkok’s Thammasat University in a pro-democracy protest, Thai police and the paramilitary opened fire, killing at least 40. The students, authorities said, were communist sympathizers.

But Theodore Mayer, an American anthropologist and Bangkok resident for more than 20 years who has supported INEB’s work, said that the some of the students of the 6 October Massacre, as the event is known, had adopted socially engaged Buddhism as an alternative to communism or socialism. One student of the time, Phra Paisal Visalo, later a monk, adapted Sivaraksa’s model for social change to co-found Sekiyadhamma, a similar network of socially engaged monks.

Children play at a Buddhist temple in Mae Sot, Thailand, in March 2023. Photo by Kalpana Jain

Socially engaged Buddhists are increasingly dealing with problems beyond Thailand’s borders. INEB has been supporting local activists and temples working with refugees from Myanmar, many of them Muslim, arriving into Mae Sot, on the Myanmar border. Earlier this year, on a tour of the local Buddhist temple, the Wat Thai Wattanaram, monks could be seen educating children of those who have been displaced.

The group is also working to quell the budding nationalism being fomented in temples across Southeast Asia. Somboon Chungprampree, executive secretary of INEB, said the network has been facilitating dialogue among Buddhist monks, including extremist groups.

“It is an ongoing process,” said Chungprampree. “We are trying to understand where people are coming from and using compassion.” The organization is working across the 10 countries belonging to the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, promoting Buddhist-Muslim talks. “There is no hope if they don’t live peacefully,” he said.

Aerial view of Bangkok, Thailand, at night. Photo by Braden Jarvis/Unsplash/Creative Commons

This article has been corrected. An earlier version implied that all, not some, of the students involved in the 6 October 1976 massacre had chosen socially engaged Buddhism over communism. Religion News Service regrets the error.