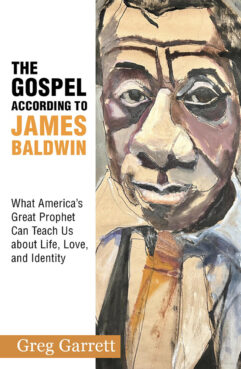

James Baldwin in London in 1969. Photo by Allan Warren/Wikipedia/Creative Commons

(RNS) — Over the past two years, lawmakers in dozens of states have taken up a crusade against “critical race theory,” passing new legislation to regulate how teachers can discuss racism, sexism and systemic inequality.

Those issues were central to the work of James Baldwin, the acclaimed American writer who died in 1987, well before critical race theory emerged as a bogeyman. Now Baldwin, whose very life bore witness to American racial strife — so much so that he escaped to Paris, where he lived most of his adult life — is enjoying a bit of a renaissance.

One scholar in particular, Greg Garrett, a professor at Baylor University, is eager to introduce a new generation of readers to the writer of short stories, novels and plays who served as a social critic par excellence, shedding light on the dark reality of American racism.

Greg Garrett. Courtesy photo

Garrett, who is white, teaches Baldwin’s work in his literature, creative writing, film and theology classes. Now he has written a book, “The Gospel According to James Baldwin: What America’s Great Prophet Can Teach Us About Life, Love, and Identity.”

The book explores the Harlem-born writer’s views on faith, race, justice and identity — all of which Garrett believes can help readers gain insights into what it means to be human and what our responsibility is to other humans. Garrett, who lives in Austin, Texas, also serves as the canon theologian at the American Cathedral of the Holy Trinity in Paris and has written widely about religion and pop culture.

Religion News Service spoke to Garrett about Baldwin and why his writings are so relevant today. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

When did you first discover James Baldwin and why did you begin to think about writing a book on him?

As a working writer who is also a teacher, my reading is pretty much limited to the things I’m bringing into the classroom. Initially I was reading Baldwin’s short stories, and then, some years ago, I read “The Fire Next Time” and was just, sort of, shattered by it. I knew he was important. But when you find yourself delivered up by a writer, and you see your country in a powerful way you hadn’t before, it’s a marker of something I want to spend more time thinking about, more time reading or, even writing about. And so I’ve been carrying “The Fire Next Time” in my backpack for a good 10 years — all over the country and all over the planet.

In some cases, “The Fire Next Time” is a little like my Bible. I’ll just open it up and start reading and find something I need to see or need to know on that day.

Have your students heard of Baldwin before they start reading him?

Generally, no. But no matter who my students are, how similar to Baldwin, or dissimilar from Baldwin, they see something in him. So if you’re a Black student or a gay student, you feel seen and represented. But my straight, white, devoutly Christian students also see themselves reflected in a really powerful way. And that was one of the things that made me say, OK, this is something I need to spend time with. I need to bring Baldwin to a large audience, some of whom have read him and some of whom never have read him. I don’t think there will ever be a semester for the rest of my teaching life where I don’t teach him.

Baldwin saw himself as a kind of Jeremiah. Why did he choose Jeremiah of all the prophets?

“The Gospel According to James Baldwin: What America’s Great Prophet Can Teach Us About Life, Love, and Identity” by Greg Garrett. Courtesy image

Well, the Hebrew prophets leaned toward justice and away from what we might call sanctity.

Jeremiah, first of all, was speaking to a pious culture about what God really wanted — not proper worship, but proper action. The second thing is that in American literature, there’s a tradition of sermons in the mold of Jeremiah. I heard many growing up in the Southern Baptist tradition: Our nation is going to hell in a handbasket and until we turn back to the Lord, the nation will continue its decline. So that was an evangelical version of the jeremiad. Baldwin delivers some of those in his essays and in his fiction and plays where he says, “If America is gonna survive, if America is gonna thrive, we have got to face our history together and move forward together in love.”

But Baldwin was not just writing jeremiads. He writes in a whole host of different literary styles. What are they?

Yes, as a literary critic, one of his first important works was a sort of scathing critique of protest literature which encompassed his mentor, Richard Wright, who never forgave him for that. He believed art that existed only to push the social message was bad art. And so that’s not to say there are not powerful social messages in his work because there certainly are. But they are not the driving engine of a Baldwin play or screenplay or novel or short story. The characters are the driving engine. Over and over again, he believed people need to be given their full complicated humanity. In some of his great works — for example, the epic novel “Another Country”— this vast cast of characters, all of whom have their own brokenness, their own yearning, their own hopes for the future. They do bad things, they do good things. There’s no attempt to set up straw men and knock them down or fake heroes and exalt them. These are real human beings doing the very best they can. If Baldwin has a piece of wisdom, he says at the end of his life, “The sum total of all my wisdom is, we can do better.”

Baldwin opposed the Nation of Islam and had mixed feelings about Malcolm X, too.

Yeah. He did not like the early Malcolm X. I point out how in an interview, Baldwin told an interviewer, “I would never want to be a theologian like that.” What he meant was, “I don’t want to be a prophet of hate.” That was exactly what he encountered in his conversations with people of the Nation of Islam. He thought that hating the people who have hated you is morally deforming. And so when he thinks about what a usable faith ought to be, he talks about how the notion of God should expand us; it should make us better, not worse. The year before he died, Malcolm X came much closer to Baldwin’s understanding of the power of love.

The theme of the “welcome table” is something Baldwin keeps coming back to, right?

Yes. My favorite Baldwin book is called “No Name in the Street.” I was just leafing through the book and I found, here on Page 36, the welcome table. And that’s a concept that appears a number of times in Baldwin’s work or in interviews. It’s the name of the play that Baldwin was working on toward the end of his life that sort of encapsulated some of the things he was hoping might someday be possible. The welcome table is drawn from a Black spiritual:

“I’m gonna sit at the welcome table one of these days.” It’s a consciousness of the possibility of some future love and acceptance that hasn’t been constructed yet. What Baldwin was really looking forward to was a world in which those identity markers wouldn’t matter anymore. The play has a multicultural cast. There are people gathered at the table who by all accounts should hate each other. But there is an incredible sympathy for each of these characters. And so, even toward the end of his life, even after all he had seen and everything he had lost, he still had this hope that someday there would be this place where we would sit and look across the table at each other and not see a Black person or a gay person or a woman or a trans man, but just a child of God.

The culture wars over critical race theory and efforts to attack histories that center Blacks and other marginalized people recall the big themes James Baldwin writes about. Is Baldwin having a moment nowadays?

The answer to that is that every moment seems to be a Baldwin moment. The Princeton professor Eddie Glaude wrote a really fine book about Baldwin for the 2020 election. He wanted to talk about what Baldwin might have thought about what was going on in the country — the dangers to democracy, the upswing in hatred and bigotry. So 2020 was a Baldwin moment, and 2023, with state legislatures and parents trying to remove the possibility of our students learning about our full history, is also a Baldwin moment. I was at the National Museum of African American History and Culture, which is one of my favorite places in the world, and on the huge back wall there’s a quote from Baldwin about history that says, “The great force of history comes from the fact that we carry it within us … history is literally present in all that we do.”

So, not choosing to confront doesn’t allow us to move forward. It’s a way of not dealing with the problem. And so if people remain in ignorance or choose ignorance, then there’s no possibility for reconciliation. If this trend continues, we’ll be still in chains. That’s something he was very clear about. In his letter to his nephew, which is the opening essay in “The Fire Next Time,” he talks about the necessity to love white people because they are trapped in this history and they are afraid to confront it. He tells his nephew the real crime is that they want to pretend innocence and remain ignorant. And that’s the crime.