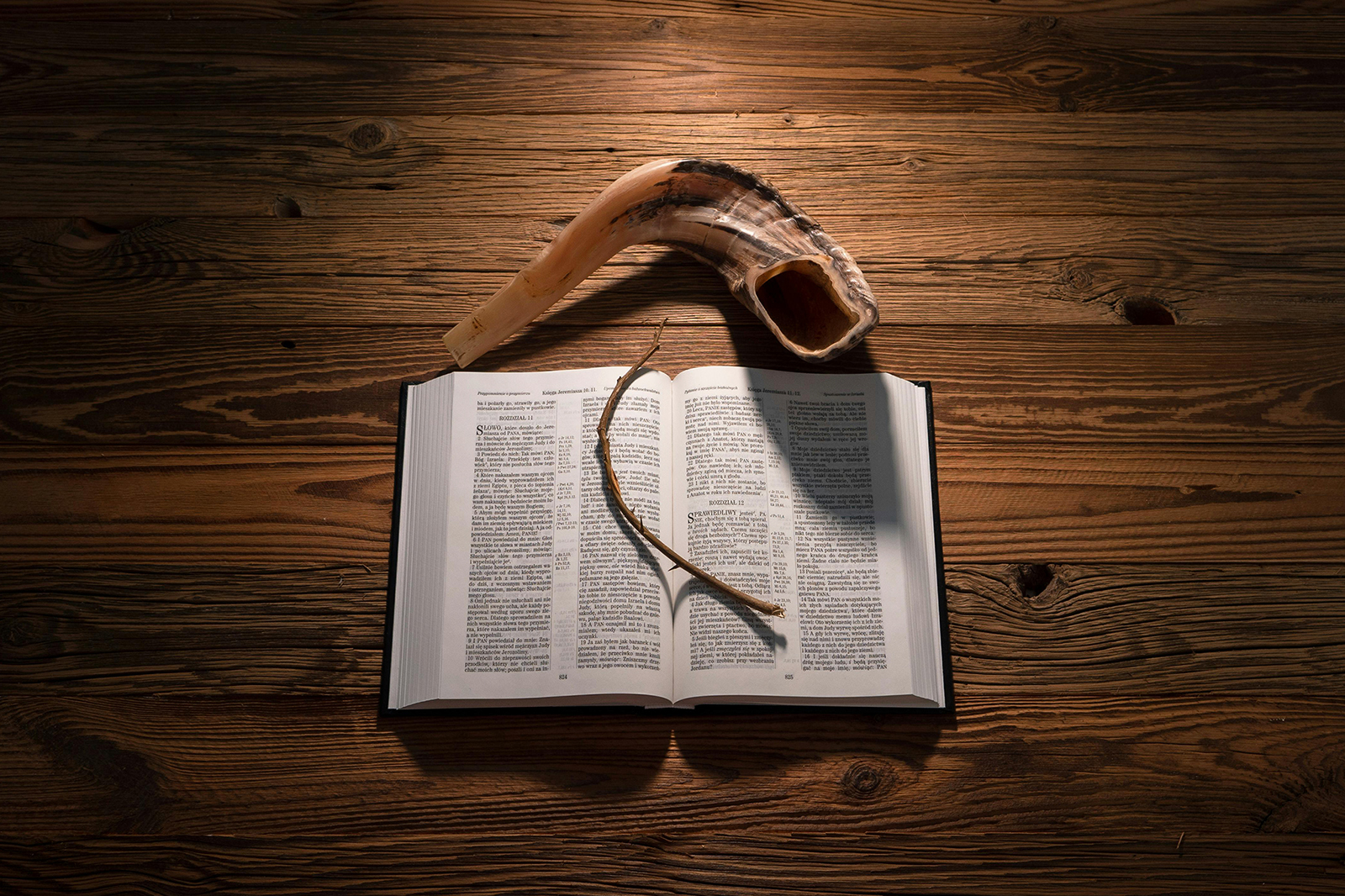

(RNS) — The Jewish celebration of the advent of a new year bears little resemblance to the sort of sentimental emoting and tipsiness we associate with Jan. 1. Rosh Hashana, the Jewish New Year, is a happy time, but a somber one as well: It is a time of divine judgment, for all humanity.

The week between the Jewish “High Holy Days” of Rosh Hashana (beginning this year on the evening of Oct. 2) and Yom Kippur (the Day of Atonement, beginning the evening of the 11th) is known as the “days of repentance.”

The recurrent season for repentance reflects Judaism’s view that all humans are imperfect and need to face what we have done wrong at various points in our lives. As King Solomon wrote in the Bible’s Book of Ecclesiastes: “There is no fully righteous person who does only good and does not sin.”

Jewish law has much to say about repentance – yes, Jewish law deals not only with things like rituals, torts and damages but also with interpersonal behavior, proper manners of speech and the human condition. The first stage of repentance, the law says, is regret, wholeheartedly wishing that one had not sinned.

Regret, though, doesn’t mean despondence, which is entirely counterproductive. Regret is an experience of pain meant to lead to gain, to determination to be better, to take steps to undermine the need for future regrets. And even if that effort fails, renewed determination is the only way to success. The smoker who ruefully says quitting the habit is easy because he’s “done it many times” elicits a cynical smile. But the fact is most smokers failed to quit repeatedly before becoming ex-smokers.

The renowned 20th-century Jewish scholar and yeshiva dean Rabbi Yitzchok Hutner once replied to a seminary graduate who had written to him about his depression over his unspecified personal spiritual failures. He had repeatedly resolved to not repeat them, the former student wrote, but had failed, and was experiencing pain over their persistence.

Hutner responded in a reassuring manner. What makes life meaningful, he wrote, is not basking in the effects of one’s “good inclination” but rather engaging, no matter the number of setbacks, in the battle against our inclination to do wrong. One sometimes loses battles, he writes, on the way to winning the war. And one must never lose sight of that ultimate goal, no matter how beaten one feels.

“Seven times does the righteous one fall and get up,” wrote King Solomon, this time in Proverbs. That, Hutner informed the young man, does not mean that “even after falling seven times, the righteous one somehow manages to get up again.” What it really means, he explained, is that it is precisely through repeated falls that a person truly achieves righteousness. The struggles — including the failures — are inherent in the achievement of eventual success.

This goes beyond Big Bird’s perceptive lesson that “Everyone makes mistakes, oh, yes they do.” It’s something qualitatively different. It’s that everyone needs to make mistakes, in order to stop making them.

Failure has been described similarly in secular contexts. Back in 1985, the late Duke University civil engineering professor Henry Petroski wrote a book whose subtitle says much: “To Engineer Is Human: The Role of Failure in Successful Design.” He makes the case that a successful feat of invention will always depend on a series of failures. Only the commission and analysis of errors, Petroski wrote, can propel any invention to perfection. “Failure,” the professor explains about engineering, “is what drives the field forward.”

“No one,” he writes, “wants to learn by mistakes, but we cannot learn enough from successes to go beyond the state of the art.”

Albert Einstein, a contemporary of Hutner and Petroski, is said to have remarked, “Failure is success in progress.” And progress is what counts.

The act of repentance, in Judaism, is a complex affair. If we have wronged someone, setting things straight with the one we’ve hurt is the indispensable first step, according to Jewish law. But that must be followed, as is the case with sins that do not involve harming other people, by introspection. That should lead to regret, indeed, to verbalizing that feeling to God. Once that is done, the final step of the repentance process is to follow: renewed determination to be better.

The determination must be sincere. The possibility of repentance is not a carte blanche to do wrong again. But, if one should fail, repentance is still an option. A battle has been lost, not the war.

Have a happy, and successful, Jewish New Year.

(Rabbi Avi Shafran writes widely in Jewish and general media and blogs at rabbishafran.com. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)