ROCKY MOUNT, N.C. (RNS) — After watching a documentary on the threat of Christian nationalism on a Tuesday evening last week, members of Word Tabernacle Church, a predominantly Black congregation about 55 miles east of Raleigh, had lots of questions.

Mostly, they wanted to know how to confront the movement’s adherents who have so distorted their faith.

“What’s one concept or two that we can really engage in conversation with people who may be under the chains of this way of thinking to help them start to transition to a free space?” asked Kyle Johnson, whose title is next generation pastor at Word Tabernacle Church.

That concern is shared by many who are grappling with an ideology that has rooted itself at the heart of Republican Party politics and in the candidacy of Donald Trump. Christian nationalists deride anyone outside their movement as evil and hell-bent on stripping Christianity from the public square.

The Rev. Jennifer Copeland, executive director of the North Carolina Council of Churches who sponsored the event, offered one answer that many were searching for.

“I would say the answer to the question is, love God, love your neighbor,” she said. “If we can think of ways to engage in conversations with our neighbors by calling on the great themes of Scripture, by reminding people that God is the God of the vulnerable, that God always tells us to look out for the people in our communities who are most vulnerable. And then maybe you can begin to ask some of the harder questions, like, do you see this policy as good or bad for the vulnerable, do you think the minimum wage is really enough for vulnerable people to support their families?”

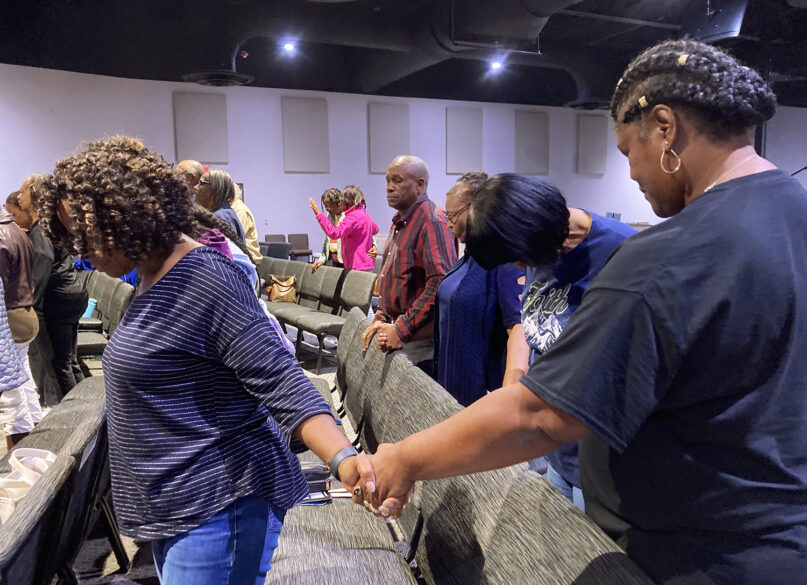

Members of Word Tabernacle Church hold hands and pray before watching a documentary on the rise of Christian nationalism on Oct. 29, 2024, in Rocky Mount, N.C. RNS photo by Yonat Shimron

Church members, such as those in the 4,000-member Word Tabernacle Church, want to better respond to family members, friends and neighbors taken up with Christian nationalism — the ideology that holds the United States is a country defined by Christianity and that Christians should rule over government and other institutions — by force, if necessary.

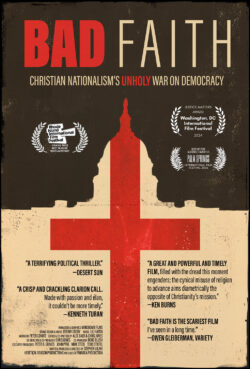

While many white evangelicals and members of nondenominational charismatic movements have been swayed by the ideology, mainline Protestants, Black churches and some Roman Catholics are now attempting to challenge its tenets. Church councils and interfaith groups have published resources, voter guides and educational materials on the subject. Some have bought licenses to screen documentaries such as “Bad Faith,” directed by Stephen Ujlaki and Christopher J. Jones, which examines the origins of Christian nationalism leading up to the Jan. 6, 2021, attack on the U.S. Capitol. (The documentary is streaming on multiple streaming services.)

RELATED: With Bible verses and Baptist zeal, Amanda Tyler offers how-to for dismantling Christian nationalism

After receiving an anonymous gift of $100,000 to combat Christian nationalism, the Rev. Jeffrey Allen, executive director of the West Virginia Council of Churches, convened a meeting of his fellow church council executives earlier this summer to decide how to use it.

“We spend a lot of time talking about, how do we humanize this? How do we avoid demonizing people? How do we present our case in nonacademic language?” Allen said.

Fourteen council leaders ended up applying for a mini grant of $3,000 to $7,200 to provide programming on Christian nationalism.

The fight against Christian nationalism has become a wide-ranging effort drawing in dozens of nonprofit groups across the nation, some of them faith-based. Among them are national groups such as Americans United for Separation of Church and State, the Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty and the Interfaith Alliance.

But state councils of churches and interfaith groups are rooted in particular places and better able to address the ways Christian nationalist ideology may be affecting local races and issues. For example, Christian nationalists may be pushing state legislatures to beef up educational funding for private Christian schools, passing laws requiring prayer in schools or displaying the Ten Commandments outside of public buildings.

Their local work can help people of faith draw connections between national ideology with no recognizable leader and the way it may be implemented in their state.

They do so not to debate their opponents but to talk to one another.

“The people in the room are already thinking about Christian nationalism as a problem,” said Copeland. “What they seem to be most grateful for is that they’re in a room full of people like themselves, where often they might feel like they’re the only person that thinks that way.”

The North Carolina Council of Churches has across the state sponsored seven screenings of the documentary “Bad Faith,” with a discussion forum after the screening. Copeland often invited Duke University historian Nancy MacLean to join her on her talks to church groups in part because understanding Christian nationalism requires a historical and political understanding of the rise of the far right.

Members of Word Tabernacle Church appreciated the event, which was also livestreamed to 300 members at home. The church, started in 2005 as a Southern Baptist-affiliated congregation, is now nondenominational. As such, it is not a member of the state’s Council of Churches, which is composed of 18 denominationally affiliated congregations. But its pastor, James Gailliard, a former Democratic state legislator, said he wants to work more closely with the council.

Lorenza Johnson of Rocky Mount, N.C., a member of Word Tabernacle Church, expressed some thoughts after watching the movie “Bad Faith.” RNS photo by Yonat Shimron

Lorenza Johnson, a church member who attended the screening in person, said he appreciated what he learned and said he felt mobilized to do more.

“We can be happy in here and shout in here and be safe and go to heaven,” said Johnson, who lives in Rocky Mount. “But in reality, we still have another generation that’s gonna be here. And if we don’t find out the power of a vote and get the right people in place, then we may be going to heaven, but we can be living in hell while we’re here.”

Although much of the effort of state councils of churches will conclude after the presidential election, several others have decided to keep going.

The Wisconsin Council of Churches, for example, is putting together a sermon series for Lent, which begins on March 5, and soliciting hymns, songs and other artwork that address ways of countering Christian nationalism.

“So often, people look at these large election cycles and they think, ‘OK, we’re, we’re going to pay attention to this issue and then once the election cycle is over, we all calm down,’” said the Rev. Kerri Parker, executive director of the Wisconsin Council of Churches. “We need to pay attention to these moral and ethical issues all along.”

The Arizona Faith Network, an interfaith group, is also going to continue exploring the issue in 2025, with a focus on religious nationalism in other faith traditions, such as Hinduism and Buddhism.

Allen said he thinks these efforts at the congregational level may be the most meaningful.

“People who are feeling lonely and left out and connecting with folks who are manipulating them,” said Allen. “I think the church can provide an alternative to that — an authentic community that doesn’t seek to take anything from them, but instead to give.”

RELATED: We tried Christian nationalism in America. It went badly.

(This story was reported with support from the Stiefel Freethought Foundation.)