(RNS) — Published 100 years ago Thursday (April 10), “The Great Gatsby” by F. Scott Fitzgerald continues to be a cautionary tale for our time.

While most attention is given — by readers of the novel or makers of film adaptations — to the parts of the story centered on its larger-than-life main character, Jay Gatsby, and the opulent, excessive, self-indulgent lifestyle led by him and his friends, there is another story within the story that offers a timely allegory, especially for Christians today.

This is the story of a quiet minor character who plays an outsized role in the plot: George Wilson.

Wilson is an auto repairman who lives outside Long Island in an industrial wasteland described as the “valley of ashes.” Literary critics have pointed out the way in which George’s name, a combination of George Washington and Woodrow Wilson, symbolizes a romantic vision of American history and traditional values. But this vision is, in reality, in decline. And not coincidentally, the deteriorating world depicted in “The Great Gatsby” is notorious for being absent of God.

Outside the gilded cage of Gatsby’s Long Island, within the gray desolation where George Wilson lives with his wife, Myrtle, in the valley, a simulacrum of God leers over their garage apartment in the form of a faded billboard sign advertising the services of an optometrist:

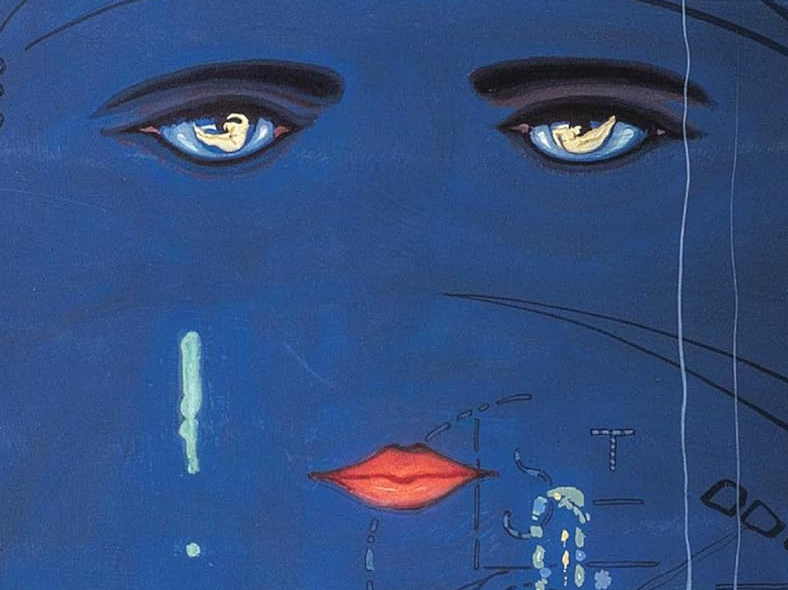

The eyes of Doctor T. J. Eckleburg are blue and gigantic — their retinas are one yard high. They look out of no face, but, instead, from a pair of enormous yellow spectacles which pass over a nonexistent nose. Evidently some wild wag of an oculist set them there to fatten his practice in the borough of Queens, and then sank down himself into eternal blindness, or forgot them and moved away. But his eyes, dimmed a little by many paintless days, under sun and rain, brood on over the solemn dumping ground.

God is so absent from the world of “The Great Gatsby” that the closest any character can get to him is to turn to this vague symbol of his omniscience and omnipresence. (The original art on the cover of “The Great Gatsby” was a painting commissioned for the book titled, tellingly, “Celestial Eyes.”)

The god of the billboard is not the real God, however, not even an icon or true symbol of God, but a marketing god, a god of advertising, business, entrepreneurship and all that made the Roaring Twenties roar: the god of the American Dream.

The American Dream, or rather the corruption of the American Dream, is one of the major themes of “The Great Gatsby.” Jay Gatsby embodies that distorted dream taken in one direction and George Wilson another.

Wilson is a salt-of-the-earth kind of guy. He wears a borrowed suit to his wedding, works hard (though unprosperously), lives in an apartment above his auto repair shop, remains committed to his wife (even when he suspects she has not done the same) and dreams of escaping the valley of ashes to start a new life afresh. Gatsby, on the other hand, borrows an entire identity and history, spins a narrative about himself and to himself, lives in an enormous mansion where he holds lavish parties, and lives in a dream world. Yet, neither Wilson’s nor Gatsby’s version of success and happiness is sustainable.

It is easy for Christian readers who encounter the story to see Jay Gatsby and tsk tsk, thinking themselves immune (or precluded from) his particular sins.

But George Wilson offers a warning against a whole set of other temptations.

In the climactic moment of the novel, George turns to God — or thinks he does — when he cries out, “God sees everything.” Here Wilson and his neighbor face the horrific car accident scene of his wife’s death:

“I told her she might fool me but she couldn’t fool God. I took her to the window”— with an effort he got up and walked to the rear window and leaned with his face pressed against it — “and I said ‘God knows what you’ve been doing, everything you’ve been doing. You may fool me, but you can’t fool God!’ ”

Realizing that Wilson is talking about the “god” of the billboard, his neighbor tries to correct, even comfort, him:

“That’s an advertisement,” Michaelis assured him. Something made him turn away from the window and look back into the room. But Wilson stood there a long time, his face close to the window pane, nodding into the twilight.

The God of the billboard — the God that is advertised and marketed and used to advance the interests of consumerism, class warfare and culture wars — is a god who fails to intervene or act. So, Wilson takes matters into his own hands and brings about a tragic end.

“The Great Gatsby” by F. Scott Fitzgerald. (Courtesy image)

Thus, there is little difference between no god and a false god. False gods simply come in many more forms: the God of the billboard, the memes, the viral posts, the talking heads, the political idolatry, the American Dream and all that is of mere human machinations.

The American Dream is built, in part, on the myth of another god, the god of self-sufficiency. Gatsby claims self-sufficiency by erasing his past and reinventing a new identity. He is a self-made man in every sense. Wilson, on the other hand, seeks self-sufficiency more literally by taking justice into his own hands and then killing himself. In the face of no god or a false god, there is, in the end, only the self.

George Wilson’s illusion — the illusion that faith and tradition will save us — is just as false as Jay Gatsby’s illusion that he can create himself. Failing to realize that both of these are merely substitutes for the true, living God will see all hell break loose.