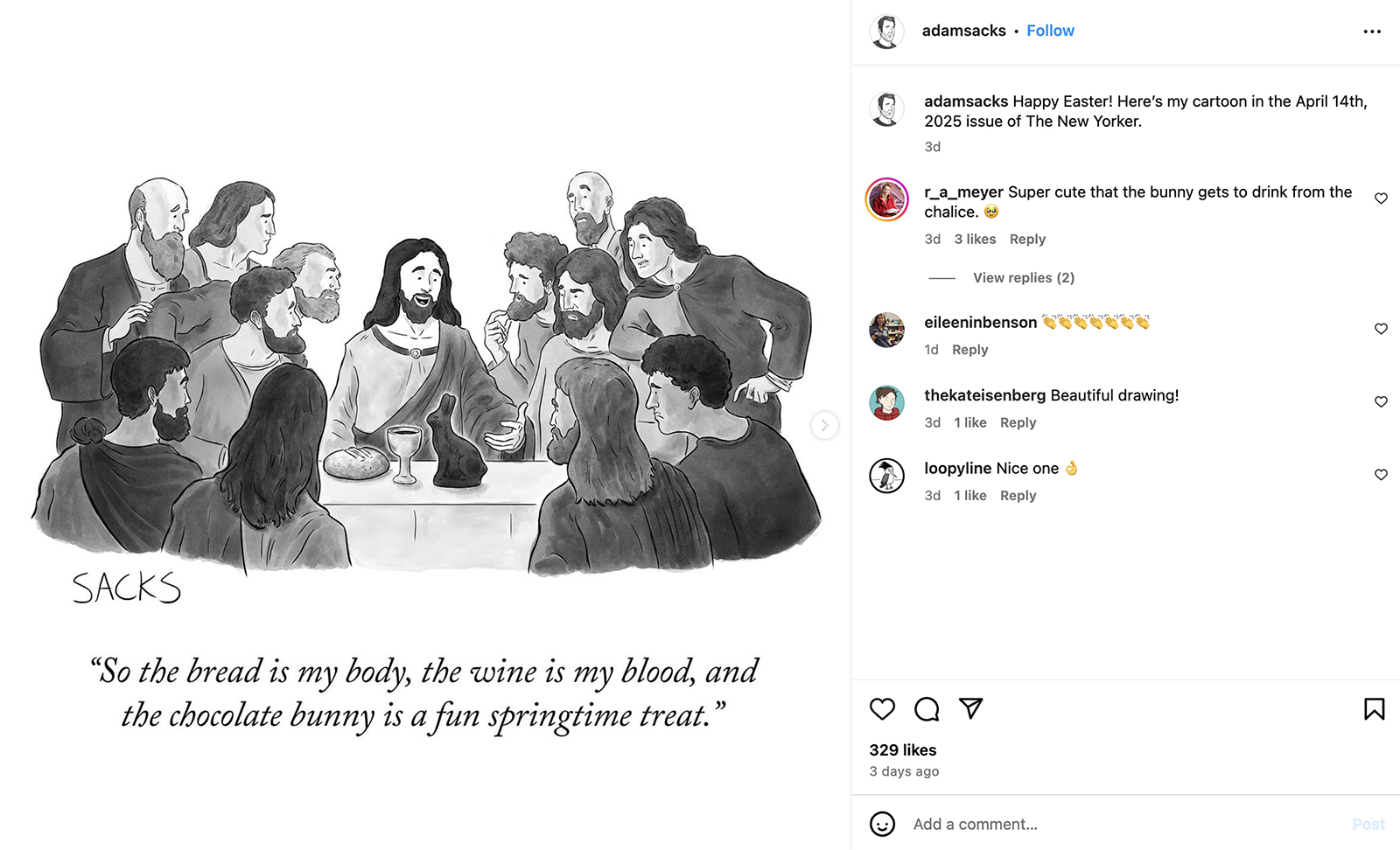

(RNS) — The New Yorker magazine has just managed to insult Christians and Jews alike with a cartoon depicting the Last Supper.

In the drawing, by Adam Sacks, Jesus, sitting at what we take to be the Last Supper, says to the apostles, “So this is my body, the wine is my blood, and the chocolate bunny is a fun springtime treat.” A loaf of bread, a chalice and a large chocolate bunny are in the middle of the table.

It’s tone-deaf. It’s outrageous. It probably earned Sacks a pretty penny.

It’s not funny.

There are at least 2.38 billion Christians in the world, most anticipating the approaching Holy Week remembrances of the passion and death of Jesus, and the Easter celebration of his resurrection.

Nearly 16 million Jews celebrate Passover these days, recollecting the Israelites’ escape from slavery in ancient Egypt.

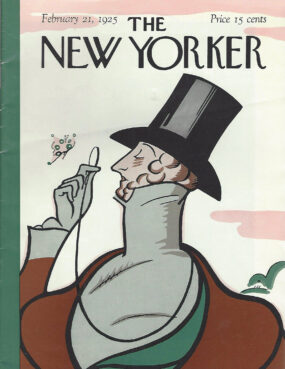

The cover of the first issue of The New Yorker, dated Feb. 21, 1925, drawn by Rea Irvin. (Image courtesy Wikimedia/Creative Commons)

For The New Yorker to poke fun at what Christians understand as the institution of the Eucharist, at a meal that might be considered a proto-Seder, is beyond tacky.

It is downright offensive.

The New Yorker began its second century of publication in February. Its initial cover showed the dandy Eustace Tilley looking down his nose through a monocle at a butterfly. Now he’s looking down his nose at a third of the world’s population, at the Christians and Jews who celebrate holidays commemorating their most precious histories and beliefs.

The cartoon in question boggles the mind and disappoints any thinking person. Its apparent disdain for religion also comes on the heels of the magazine’s awkward errors in usage in an article about Catholic sisters in Texas visiting female death row inmates in its February 17-24, 2025, issue.

Perhaps the most respected literary journal published in the United States, The New Yorker was once a paragon of precision; its fact-checking was legendary. But in Lawrence Wright’s story appear phrases such as “… she performed Mass with Deacon Ronnie and a priest.” Later, Wright describes the Eucharist as something “that evokes what Jesus served at the Last Supper.” These lapses demonstrate — what? Sloppy editing or just plain ignorance?

People “attend” or “assist at” Mass, and the Eucharist, much more than a dinner entrée, was not “served” at that first instance of Communion, but consecrated. Wright’s story provoked a complaining letter to the editor in the April 7 issue, but, in a defiant testimony to its unrepentant tone-deafness, the magazine headlined the letter, “For Christ’s Sake.”

A magazine plays to its audience, and it seems The New Yorker, like all publications these days, wants to draw younger readers. That could explain its other changes, including relaxing bans on foul language in essays and stories and other unfunny cartoons.

Pointedly offending Christians and Jews in this season is not the way to keep longtime readers. The magazine may explain its apparent changes, as it did some years ago. When asked why Eustace Tilley landed on the first cover, The New Yorker’s first art director responded, “I don’t know. It just seemed like the right thing at that time.”

Maybe then, but not now.