(RNS) — When Argentine native Jorge Mario Bergoglio took office as Pope Francis in March of 2013, few expected he would have success as a global diplomat. As archbishop of Buenos Aires, he avoided foreign travel because it took him away from mi esposa, as he referred to his diocese — “my wife.” The man who would be one of the most traveled popes in history preferred public transportation and weekend trips to local shantytowns.

But Francis proved to be a pope of surprises.

By prioritizing what he called “the peripheries” — those places distant from Rome and the international power centers in Europe and the United States — he restored the perception of the Vatican as an independent actor, located in Europe but universal in perspective. Francis himself was so independent, in fact, that Western intelligence agencies feared him, watched him before he was elected and immediately launched a slanderous campaign.

Often conveyed with symbolic gestures that overcame language barriers, Francis’ diplomacy of encounter established new relationships across borders of faith.

He also refused to observe diplomatic isolation of bad actors. Even as Cold War hostility between East and West reemerged, the pope offered to meet Russian Orthodox Patriarch Kirill “wherever you want,” a wish that came true in 2016 at an airport in Havana. The two-hour encounter was a historical first, facilitated by joint efforts to protect Christians from genocide in the Middle East and Africa.

Even after Russia invaded Ukraine, he hesitated to criticize Kirill or Russia. Instead, he lamented the “fratricidal violence” between Christians. When Francis suggested that NATO “barking at Russia’s door” contributed to the invasion, he was roundly criticized.

Pope Francis, left, and Russian Orthodox Patriarch Kirill exchange a joint declaration on religious unity in Havana on Feb. 12, 2016. (AP Photo/Gregorio Borgia, Pool)

The foundations of Francis’ diplomacy, so different from that of his predecessor, Pope Benedict XVI, lie in his life back in Argentina. At the unusually young age of 36, he was selected as provincial, or leader, of the Society of Jesus in the country. The following decade, from 1974 to 1983, is remembered as the country’s “Dirty War,” when ordinary citizens fought against a dictatorial government. Francis often hid, defended and smuggled out people who opposed the regime.

The experience led him to resent ideology, which foments hate, and to focus on human dignity over deadly political theater. Even then, he governed as a pastor, not a politician.

In 2007, Catholic bishops from all Latin America gathered in Aparecida, Brazil, where then-Cardinal Bergoglio edited the final document calling on believers to become “missionary disciples” of the gospel. It’s been called the blueprint for Francis’ pontificate and reflects his Jesuit background. Founded in 1540, the Jesuit order committed its members to spreading the Word of Jesus Christ, particularly in Asia, where it was unknown. (As a young priest, Bergoglio requested to be sent to Japan, but he was turned down due to health concerns.)

The first Jesuit ever elected pope, Bergoglio was bound to lead the Catholic Church out of its comfort zone, to engage with overlooked places and people. In Francis’ first apostolic document, Evangelii Gaudium (Joy of the Gospel) in 2013, he wrote, “Each Christian and every community must discern the path that the Lord points out, but all of us are asked to obey his call to go forth from our own comfort zone in order to reach all the ‘peripheries’ in need of the light of the Gospel.”

Another sign of his diplomatic approach was his choice to be called Francis, after St. Francis of Assisi. Famous for self-enforced poverty and a love of animals, St. Francis was also a daring diplomat who crossed Christian-Muslim battle lines in northern Egypt in 1219 to meet the sultan Malek al-Kamil, with whom he engaged in dialogue for some 20 days.

In 2014, as his first European destination outside Italy, Francis selected Albania, where the largest religious community is Muslim and where he aimed to highlight the country’s tradition of religious harmony.

Pope Francis greets Sheikh Ahmed el-Tayeb, the grand imam of Egypt’s Al-Azhar, after an interreligious meeting at the Founder’s Memorial in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, on Feb. 4, 2019. (AP Photo/Andrew Medichini)

His outreach to the Muslim world was more than a commitment to interfaith dialogue; he saw it as a way to build peace. Relations between the Holy See and the grand imam of al-Azhar, one of Sunni Islam’s most esteemed leaders, hit a low in 2011 when the current grand imam, Ahmed el-Tayeb, broke off communications over a statement Benedict made about terrorism in Egypt.

Francis proceeded to reengage el-Tayeb over time, step by step, sending an envoy to el-Tayeb to apologize (2015), hosting him at the Vatican (2016), then visiting the scholar in Cairo (2017) where they declared in a joint statement that violence and faith are incompatible.

The experience led to a landmark event in 2019: Francis and el-Tayeb on a futuristic stage in Abu Dhabi signing the “Document on Human Fraternity,” uniting efforts against religious extremism and the political manipulation of religion. The papal visit led to the first public Mass on the Arabian Peninsula — made possible by the cultivation of personal dialogue.

Francis said his 2020 encyclical Fratelli Tutti (“All Brothers”) was also inspired by this encounter, and he backed it up with respectful relationships with leaders around the Muslim world, including Bahrain, Bangladesh, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Morocco, Oman and the United Arab Emirates.

For Francis, personal gestures in which he would go a visual “extra mile” took on global significance. In 2021, Francis made a pilgrimage to see Shia Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani in the holy city of Najaf, Iraq. Walking through alleys too narrow for a car, Francis made his way to the wise man’s modest living room. Al-Sistani had refused meetings with Americans, as invaders, but Francis, having consistently criticized arms merchants fomenting conflict, had built up credentials as a man of goodwill.

Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani, left, meets with Pope Francis in Najaf, Iraq, on March 6, 2021. (Photo courtesy of Office of the Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani)

In 2019, Francis invited South Sudan’s president and three vice presidents, all Christians, to a retreat in his Vatican residence to contemplate reconciliation despite the country’s recent civil war. As the meeting concluded, Francis spoke to the small group, then kissed their feet, one by one, a nonverbal blessing and an astonishing act of humility.

His interactions in the Holy Land were based on the same sense of personal encounter. Approaching Manger Square in Bethlehem in 2014, Francis spontaneously climbed out of his popemobile, walked a few steps to a giant Israeli barrier wall, placing his right hand flat on the cement while bowing his head in prayer above red graffiti, proclaiming, “Free Palestine.” It was an astonishing act of public sorrow — and defiance — broadcast live to the world. Later, after the Israel-Hamas war broke out, he made nightly phone calls to the only Catholic Church in Gaza. His last call was April 19, two nights before he died.

For many, diplomacy is a secretive pursuit, but Francis sought to spread the practice widely. With no economic or military interests and no political agenda, the Holy See is free to pursue the common good for all. The Vatican is never compelled to jump on a partisan train.

In Evangelii Guadium, he shared four rules guiding engagement with the world, meant for his diplomatic corps and the faithful. Briefly seeing how each principle was applied helps make them real.

First, time is greater than space: Because the church believes God’s hand is shown in history, the Christian’s job is to start good processes without trying to control outcomes. In time, positive results emerge.

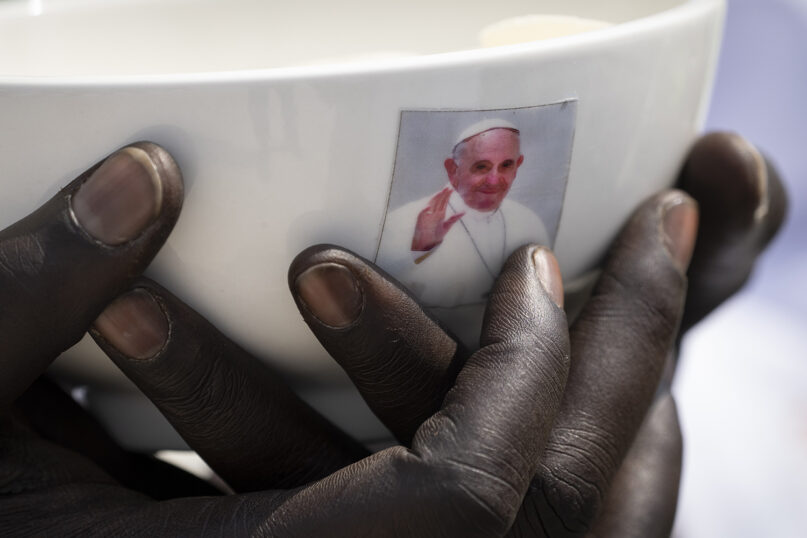

A priest holds a sacrament bowl showing a photograph of Pope Francis at a Holy Mass at the John Garang Mausoleum in Juba, South Sudan, Feb. 5, 2023. (AP Photo/Ben Curtis)

In that spirit, Francis’ diplomatic team managed to sign an agreement with Beijing regarding the joint selection of bishops, which had been in the works since the 1980s. Although criticized by U.S. leaders such as Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, the agreement preserved the succession of episcopal power going back to the apostles, crucial to Catholic sacramental integrity. It also began healing the problem of two parallel church structures, official versus underground. The agreement has led to 11 jointly appointed bishops.

Next, reality is more important than ideas. That rule could be seen in the Vatican’s mediation to normalize bilateral relations between the U.S. and Cuba in 2014. Rome stepped in as a guarantor between countries with very low trust. To Francis, ideological debates from the past were irrelevant to the best interests of people in Cuba and the U.S. alike.

Third, unity prevails over conflict. As peace talks in Colombia were on the verge of breaking down in 2016, in part because a current and a former president were at odds, Francis called both to Rome to talk, adding the persuasion of his spiritual authority with two Catholic laymen. Six months later, the government and main rebel group, FARC, signed peace accords. As promised, the pope visited three months after that. Unity was affirmed.

Finally, the whole is greater than the parts. In Ukraine, Francis’ diplomatic efforts were mainly frustrated because the Western powers renounced dialogue. He tried to convey that the whole of Christianity is sacred, so peace must be found among its warring factions, but throughout his papacy, the situation was careening toward conflict. Instead, he continued humanitarian aid to all.

Francis was vindicated when the principal powers, Moscow and Washington, reengaged in diplomacy to end the war.

(Victor Gaetan, a senior correspondent for the National Catholic Register, is the author of the 2021 book “God’s Diplomats: Pope Francis, Vatican Diplomacy, and America’s Armageddon.” The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of RNS.)