(The Conversation) — President Donald Trump has praised the Gilded Age, which he believes was a time of immense national prosperity thanks to tariffs, no income tax, and few regulations on business.

Similar to today, the late 19th century was a time where a small group of men enjoyed immense wealth, privilege and power to shape the nation. It was a time of immense inequality, as factory and housing conditions crushed the lives of the poor.

And it was a time of white Christian nationalism.

In Northern cities, reformers saw the wealth gap, the plight of workers and the squalid conditions in tenements as undermining their vision of a Christian America. Fueled by faith, the Social Gospel movement worked to expand labor rights and improve living conditions at the turn of the 20th century.

At the same time, many of these white Protestant activists believed their own culture and race to be superior, and this prejudice hindered their efforts. They often spouted anti-Catholic and anti-immigrant rhetoric, and mostly ignored Black workers’ plight.

One of Jacob Riis’ many photographs of living conditions on New York’s Lower East Side.

Bettmann via Getty Images

Ever since the Puritans landed, white Christian nationalism has informed how many Protestants try to shape their country – a history I trace with church historian Richard T. Hughes in the book “Christian America and the Kingdom of God.” But Christian nationalism has taken dramatically different forms over time. The progressive Social Gospellers of a century ago are a particularly striking contrast to the conservative Christian right that has shaped U.S. politics for half a century, up to today.

Guardians of a Christian nation

There are many differences between Christian nationalism then and now. Like many conservative Christians today, however, the Social Gospellers believed that the United States was uniquely chosen and blessed by God, and called to be a Christian nation. They saw themselves as the rightful guardians of that mission. And though the country was still overwhelmingly Protestant, they feared they were losing influence.

New research explored the history of the Bible – research that many Christians feared would undermine people’s trust in Scripture as the word of God, by emphasizing its human composition. New scientific ideas about the Earth’s creation and human evolution challenged their visions of an all-powerful, all-knowing God. Meanwhile, rapid industrialization and urbanization had created new social challenges, such as workers’ safety and living conditions, leading some to reject faith as irrelevant to their needs.

Social Gospellers wanted to vindicate Christianity and show it was still relevant to modern life. But white leaders’ vision of what a Christian America should look like conflated their Protestant faith with their race and culture.

Josiah Strong, for example, was a Congregationalist minister known for promoting factory safety. But he stoked fear of Catholic immigrants and endorsed the expansion of the U.S. as a benevolent empire. The Anglo-Saxon race “is destined to dispossess many weaker races, assimilate others, and mold the remainder,” Strong argued in his 1885 book, “Our Country.”

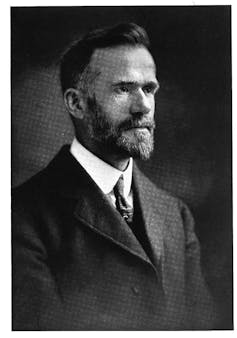

Baptist reformer Walter Rauschenbusch.

Library of Congress/Corbis/VCG via Getty Images

Another Social Gospel reformer, Northern Baptist theologian Walter Rauschenbusch, railed against unrestrained greed, political corruption, militarism and contempt between elites and the working class. But he shared the white supremacy of his age. God was favoring Germanic and Anglo-Saxon people, he claimed, to enact God’s purposes.

“Other races are as dear to God as we and he may be holding them in reserve to carry His banner when we drop it,” he wrote in an undated article. But it was part of God’s plan, he believed, for Northern Europeans to “hold the larger part of the world’s wealth and power in the hollow of their hands and the larger share of the world’s intellectual and spiritual possessions in the hollow of their heads.”

The ‘right’ kind of Christian

Though many white Protestants felt threatened by the challenges of immigration, they were still a clear majority, and they presumed that most Americans would endorse applying Christian ethics to public policy and social reform.

Jane Addams speaks to visitors in 1935 at Hull House, a settlement house in Chicago that she co-founded in 1889.

National Archives via Wikimedia Commons

What’s more, women gaining the right to vote in 1920 meant Social Gospel leaders expanded Protestants’ power at the ballot box. Many Social Gospel leaders embraced women’s suffrage because women were already leading supporters for their causes: For example, Frances Willard, who promoted temperance and workers’ rights; and Jane Addams, who ran a Christian “settlement house,” or community center, for the poor.

But in another sense, demographics were not on their side. The U.S. might have been a very white and Christian country, but in some Social Gospellers’ minds, the era’s waves of immigrants were not the “right” kind of Christian: Northern European and Protestant. Immigration was shifting from Great Britain, Ireland and Germany to Russia, Poland, Hungary and Italy. While Protestants far outnumbered Catholics nationally, Strong wrote that they were double the Protestant population in major cities like New York, Chicago and Philadelphia.

A Polish mother and her nine children waiting at Ellis Island.

U.S. National Park Service

Strong argued that Catholic immigrants were lazy, prone to alcoholism and criminal activity, and willing to sell their vote to corrupt city politicians. He claimed they would corrupt the morals of Anglo-Saxon Americans, and that if the Catholic population grew, it would undermine Protestants’ religious liberty.

Nativist views like these led to the National Origins Act of 1924, which restricted the number of immigrants. Quotas for each country were based on the profile of the American population in 1890 – an attempt to maintain Protestant dominance against Catholic and Jewish immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe. That distrust also kept Social Gospellers from partnering with Roman Catholic leaders on shared concern for workers.

Flourishing for all, or some?

Still, when it came to workers’ basic needs, reformers cared deeply about improving circumstances for the “least of these.” The movement was strongly influenced by the biblical parable of the sheep and the goats: verses in the Book of Matthew where Jesus promotes feeding the hungry, caring for the sick, clothing the naked and visiting those in prison.

Social Gospellers aimed to prove that Christianity could answer the social challenges caused by industrialization, urbanization and immigration. For the most part, they sought to use their privilege in ways that promoted the flourishing of all Americans, such as expanding labor rights and providing services to the poor through settlement houses.

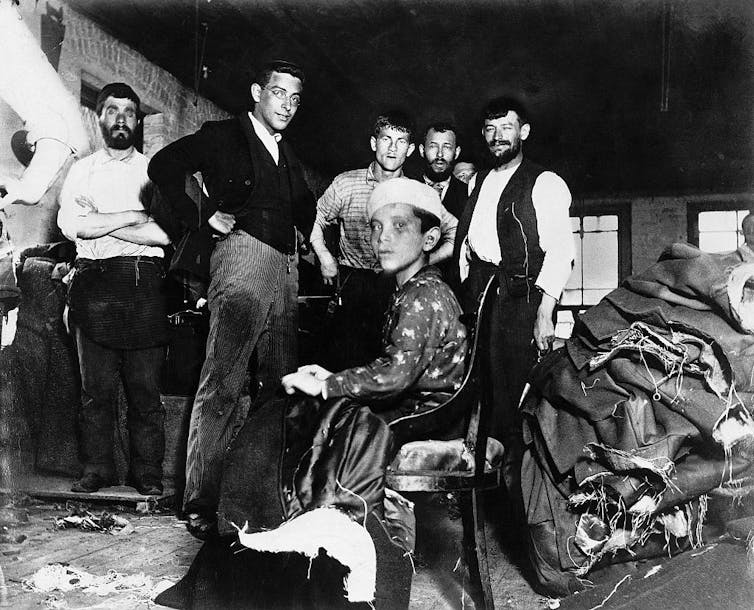

A photograph by Jacob Riis in a small New York City sweatshop in the 1880s.

Bettmann via Getty Images

In 1908, for example, the Federal Council of Churches adopted a 14-point statement called the “Social Creed,” affirming that churches should support reforms “to lift the crushing burdens of the poor, and to reduce the hardships and uphold the dignity of labor.” While some of the reforms they called for are taken for granted today — like one day off per week — other calls, like a living wage for all, are yet to be realized.

Over the past half-century, the modern Christian right, too, has feared that its vision for the nation is eroding. Conservative churches have seen their influence drop as more Americans move away from organized religion and reject their rejection of LGBTQ+ people.

I — along with other scholars — argue that these fears have helped fuel resurgent Christian nationalism today. Since merging with the tea party movement during the Obama administration, the Christian right has increasingly embraced an anti-immigration and anti-minority stance, fearing the loss of its own standing.

Like the Social Gospellers of a century ago, the Christian nationalists of recent decades are wary of religious and racial change in their country. Yet the movement’s priorities – often focused around its vision of families, sex and gender – are starkly more limited than the broader quality-of-life issues that Social Gospellers addressed.

Both groups desired an America rooted in biblical values. But each interpreted Scripture through its own lens, seeking to remake America in its own, white Protestant image.

(Christina Littlefield, Associate Professor of Communication and Religion, Pepperdine University. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)

![]()