(RNS) — On the last day of this year’s U.S. Supreme Court term, the justices ruled that parents may withdraw their children from public school classes where LGBTQ+ issues are discussed in an inclusive way.

The right of parents “to direct the religious upbringing of their children would be an empty promise if it did not follow those children into the public school classroom,” wrote Justice Samuel Alito for the court’s six-member conservative supermajority in Mahmoud v. Taylor. “We have thus recognized limits on the government’s ability to interfere with a student’s religious upbringing in a public school setting.”

What Alito did not do was indicate the extent of those limits. In a dissent signed by the court’s three liberals, Justice Sonia Sotomayor contended that the decision would have the effect of permitting students to opt out of any school activity that violates their parents’ religious beliefs.

On that basis, I wrote a quiz several weeks ago, asking readers to answer yes or no to whether they would permit opt-outs for a dozen possible school activities.

Among the readers who chose to take the quiz, there were yeses and nos on both sides of every question, though not in equal measure. Twice as many thought students should be permitted to opt out of saying the Pledge of Allegiance — a permission declared as a matter of constitutional right by the court in its Barnette decision back in 1943. Likewise, a strong majority favored letting students opt out of the kind of coach-led prayer permitted by the court in 2022 in Kennedy v. Bremerton.

On the curricular front, readers opposed letting students opt out of favorable accounts of successful women politicians and religious liberty and (narrowly) evolution, and of unfavorable accounts of slavery and of Satan (in Milton’s “Paradise Lost”). They did support an opt-out of the “Song of Roland,” the 11th-century epic poem, for its negative portrayal of Islam.

Those who participated in the quiz were evenly split when it comes to opting out of mentions of the Bible (for positive views of the Judeo-Christian God); “The Merchant of Venice” (for negative views of Jews); Mozart’s “The Magic Flute” (for promotion of Freemasonry); and critical teaching about the Crusades.

The problem, of course, is that American courts don’t get to differentiate legitimate from illegitimate religious beliefs. All judges are allowed to determine is whether a belief is sincerely held. Which is to say that without establishing a compelling government interest in promoting a particular point of view — democratic governance? religious liberty? — it would be impossible to forbid faith-based opt-outs according to the Alito doctrine.

In fact, what Mahmoud v. Taylor does is radically revise the court’s religion jurisprudence. It portends an overthrowing of the way the court has understood the free exercise and establishment clauses for decades.

But don’t take my word for it — take the word of Josh Blackman, the conservative libertarian law professor recently named by President Trump to his Religious Liberty Commission’s advisory board. Alito’s enunciation of the principle that students bring their religious liberty into public school classrooms “would have been unthinkable a decade ago,” he writes.

Blackman points to the difference between how the court handled Kennedy v. Bremerton versus how it handled Mahmoud v. Taylor. In the first case, the court waved away concerns that students would be indirectly influenced by a coach leading prayer in the locker room; in the second, it wanted to be sure that students are protected from being indirectly influenced by LGBTQ-inclusive books.

The difference, Blackman writes, has to do with what the students are to be protected from:

I think the distinction can be stated simply: the Court finds that the government cannot indirectly coerce children who are exercising their religious beliefs, but the government can indirectly coerce children who are not exercising their religious beliefs. Stated differently, children have the right to be free from indirect coercion that could affect their religious development, but children have no right to be free from indirect coercion that could affect their secular development. The government can’t impose values that are hostile to religious beliefs, but can impose values that are hostile to secular beliefs.

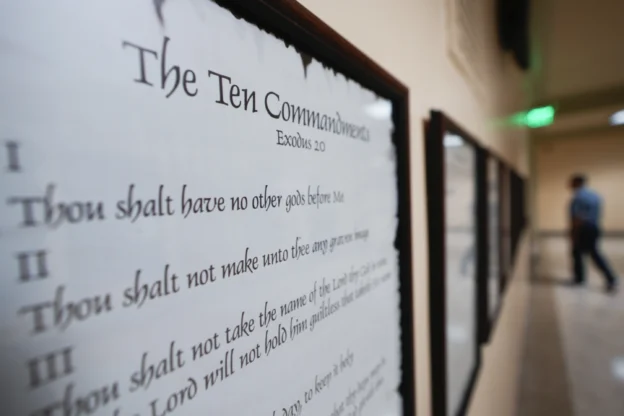

To understand how this might change how we understand religion in schools, suppose, for example, the court takes up a case brought by secularist parents to the posting of the Ten Commandments in public classrooms, as a number of states have recently mandated, in ostensible violation of the court’s 1980 decision, Stone v. Graham.

The court’s response could well be: “Too bad.”