(RNS) — Growing up as a child of a Focus on the Family executive in the 1990s, Amber Cantorna-Wylde belonged to a seemingly idyllic family at the epicenter of American evangelicalism.

Her household was infused with the teachings of Focus on the Family founder James Dobson, who endorsed strong marriages, clear family hierarchy and strict discipline for children as antidotes to rising divorce rates, second-wave feminism and the sexual revolution. At age 13, Cantorna-Wylde was surrounded by family and friends as her father placed a silver purity ring on her finger, symbolizing her commitment to virginity until marriage.

“There was an expectation that was put on us, because of who my father was and the reputation that we had in the community, that we were supposed to behave a certain way,” said Cantorna-Wylde, whose father, Dave Arnold, was the executive producer of the smash hit children’s Christian radio program “Adventures in Odyssey.”

Amber Cantorna-Wylde. (Courtesy photo)

But Cantorna-Wylde, now 40, claims it was Dobson’s teachings on family that tore her own apart. After she came out as gay, her parents stopped speaking with her — a decision she says resulted from Dobson-approved parenting advice.

When Dobson died last month at age 89, Cantorna-Wylde was one of hundreds of evangelicals raised with Dobson’s precepts who took to social media to question his legacy. Many of these former “Focus on the Family kids” say their families were ruptured by parents who closely followed Dobson’s teaching. For them, the parenting methods that promised stability instead fragmented the very relationships they were intended to uplift.

A University of Southern California child psychologist, Dobson burst onto the parenting advice scene in 1970 with the publication of “Dare to Discipline.” An answer to the popular Dr. Benjamin Spock, whom Dobson called too permissive, “Dare to Discipline” framed parent-child interactions as a power struggle and instructed parents to discipline children decisively and early. Dobson argued that physical discipline as young as 15 months would stave off teenage rebellion and the threat to the American family posed by the upheavals of the 1960s.

“Dobson was able to meet the moment in terms of speaking to people’s fears and panic, and offering this voice of moral clarity,” said scholar Kelsey Kramer McGinnis, who co-authored the forthcoming book “The Myth of Good Christian Parenting” with Marissa Burt.

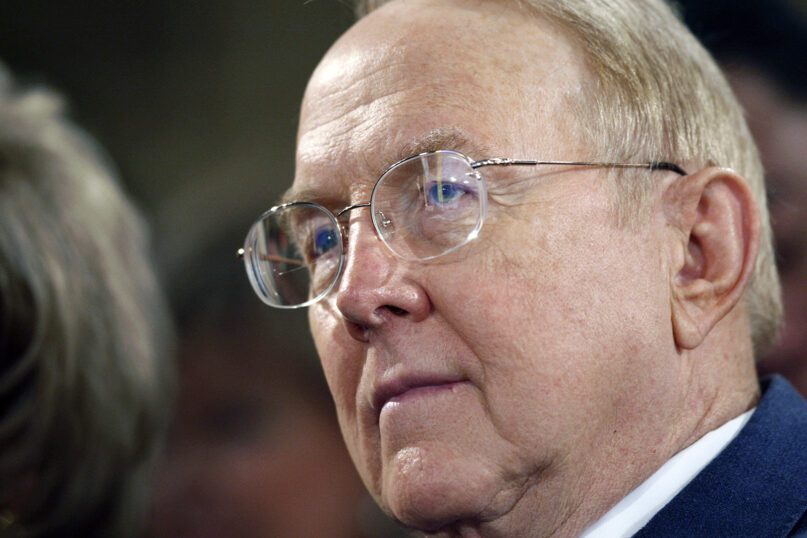

FILE – In a March 11, 2008, photo, Christian evangelical leader and founder of Focus on the Family James Dobson at the National Religious Broadcasters’ 2008 convention at the Gaylord Opryland Resort and Convention Center in Nashville, Tenn. (AP Photo/Charles Dharapak, file)

In 1977, Dobson founded Focus on the Family and began to dole out advice via more books, as well as magazines and radio, reaching millions of readers and listeners. His 1978 book “The Strong-Willed Child” offered corporal punishment to quell a child’s defiant behavior without breaking their spirit. Over two decades, Dobson extended his authority to politics, pushing his views opposing abortion and LGBTQ+ rights. “He had an unparalleled political, ministerial access to families within white American evangelicalism,” said Burt.

In practice, many parents implemented his advice selectively. McGinnis said her evangelical parents read Dobson’s books but didn’t take them as license to be authoritarian. For others, Dobson’s teachings were a tempering force, providing guardrails for corporal punishment. “My father took to heart Dobson’s lessons that as the male head of the household, he had the responsibility to lead the family with love and compassion,” Messiah College history professor John Fea wrote in a 2024 Atlantic article. “Such an approach to family life was countercultural to the working-class, patriarchal, immigrant culture in which he was raised.”

But in some Dobson families, children were expected to suppress their individuality and comply immediately with their parents’ wishes in moments of conflict, often under threat of physical force. “My job was to make things smoother for them,” said Lauren Smallcomb, 38, who was raised in a Roman Catholic and, later, evangelical family in upstate New York.

One of three siblings, Smallcomb played the part of her family’s “golden child,” she said. “I traded my emotional needs and my needs for authenticity so that I could be accepted and loved by my parents.”

Dobson laid the groundwork for more extreme takes on Christian parenting. When she was in her early teens, Cait West’s family, already following Dobson, began taking cues from Vision Forum founder Doug Phillips. West, author of the 2024 memoir “Rift,” became a stay-at-home daughter who wasn’t permitted to go to college and whose father controlled who she would marry. “James Dobson laid out the foundation for what I would consider the radicalization of my family,” West told RNS.

Child development experts and numerous medical organizations have condemned Dobson’s championing of corporal punishment. Therapist Krispin Mayfield, who, with his partner D.L. Mayfield, co-created the multimedia “Strongwilled” project examining religious authoritarian parenting, told RNS that when kids learn that pushing against parents results in physical pain, that lesson often continues into adulthood.

“To push against your parents, to disobey them, to have to set boundaries, to practice your own autonomy is associated with being physically hurt,” said Mayfield. “Staying safe is ‘don’t push back, don’t disagree, don’t disobey.’ Compliance keeps you safe.” Families that have enforced unquestioned compliance as a child’s default response may as a result lack the tools to navigate these divides.

Smallcomb, whose forthcoming book “Golden Child” details her story of estrangement, first questioned her parents’ Dobson-influenced methods when she became a parent herself. “I began to realize that compliance wasn’t everything, and wasn’t even really the goal,” said Smallcomb. By 2020, Smallcomb was also questioning her family’s beliefs on race and the role of Christianity in politics, disagreements that she said exposed her parents’ ongoing expectations of obedience.

“It was everything to do with my parents’ parenting style, because they were unwilling to evolve and do the necessary pivots that our relationship required for them to parent me well,” said Smallcomb of her family’s estrangement.

Lauren Smallcomb holds her book, “Golden Child.” (Photo by Arada Photography)

Twenty-seven percent of Americans are estranged from a relative, according to a 2019 study at Cornell University. Psychotherapist Karl Melvin, who specializes in dealing with family estrangement, challenged the narrative that choosing estrangement is selfish — he told RNS that estrangement is a “long, torturous process” with its own slew of negative consequences.

Estrangement can also take many forms. Some families have limited, rather than no, contact; for others, it’s temporary. Dawn Burns, a writer and professor at Michigan State University, grew up in a Dobson home. Disagreements over parenting approaches and, later, over Burns’ female partner, led to periods of distance and estrangement between Burns and their parents. But over the past few years, Burns has been returning for occasional visits.

“On my end, I go back being fully myself — I don’t hide my marriage to my wife, Bex … or my queerness,” said Burns. “I also don’t place a demand on (my parents) that they accept my narrative and reject theirs — that never works and is fruitless and binary and all the things I fight against these days.”

Dawn Burns as a youth, left, and in adulthood, right. (Courtesy photos)

Parents, too, are deeply impacted by estrangement. Many who raised kids via Dobson’s methods feel surprised or betrayed when their children limit contact; not only were they promised strong families, but because their kids acted compliant for years, they never realized there was a lack of authentic connection.

“It betrayed the entire family,” said Burt. “Certainly, children had the brunt of it. But in many situations, parents were both victims and victimizers.”

Today, Focus on the Family, responding to apparent demand, is offering advice for parents estranged from their adult kids. Focus on the Family President Jim Daly has said one of the “top calls” the organization’s counseling team receives is from parents of adult children grappling with estrangement. “We hear often about feelings of resentment, sadness, anger, grief between the parents and their children,” Daly said in a 2021 broadcast series called “Healing Parent and Adult Child Relationships.”

In 2022, Focus on the Family launched a series of articles and videos emphasizing the importance of listening to adult children without judgment, honoring their boundaries and taking the lead on reconciliation. Estrangement, the series argues, is rarely the responsibility of only one party. Focus on the Family contributor and Christian psychologist John Townsend says adult children can be too hesitant to forgive, and that parents often mistakenly extend controlling parenting tactics into a child’s teen years.

“What I would love to hear being taught is that estrangement in and of itself is not the problem, it’s the fruitless outcome of a rotting tree beneath it that attempts to coercively shape children in families to become exactly like their parents in beliefs, values and actions,” said Smallcomb.

“Without fully honoring your child’s authenticity and individuation, adult children will continue to find their own way to embrace their autonomy and agency, and estrangement will be a natural by-product.”