(RNS) — When it comes to going to church, a generational pattern is playing out in many households around the world: Grandparents never miss Sunday service; parents attend only on holidays; children, who describe themselves as “spiritual but not religious,” rarely attend at all as adults.

A new study, published in August in the journal Nature Communications and conducted by researchers at the University of Lausanne, Oxford University and the Pew Research Center, sought to explain the ebbing of religiosity across generations.

Drawing on data from Pew, the World Values Survey and the European Values Study, the authors looked at secularization and religious change across more than 100 countries and major religious traditions.

“We hope this article is useful as a kind of grand narrative about what’s going on in the world, a model of how to see global religious change,” Conrad Hackett, one of the authors, told RNS.

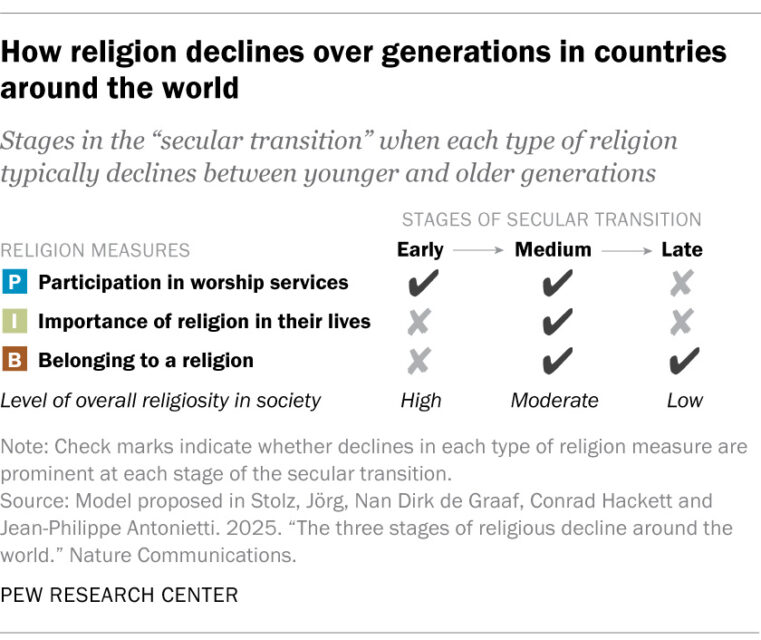

The researchers describe a sequence in how religious life tends to decline across generations. First, participation in worship services drops. Next, people report that religion becomes less important in their lives. Finally, formal religious affiliation declines. They refer to this as the Participation–Importance–Belonging, or P-I-B, sequence.

“We’re capturing a story about institutional forms of religion. It’s an interesting measure because it’s not about a specific belief, but their assessment of how much religion is shaping their decisions in their everyday life,” Hackett told Religion News Service.

“How religion declines over generations in countries around the world” (Graphic courtesy of Pew Research Center)

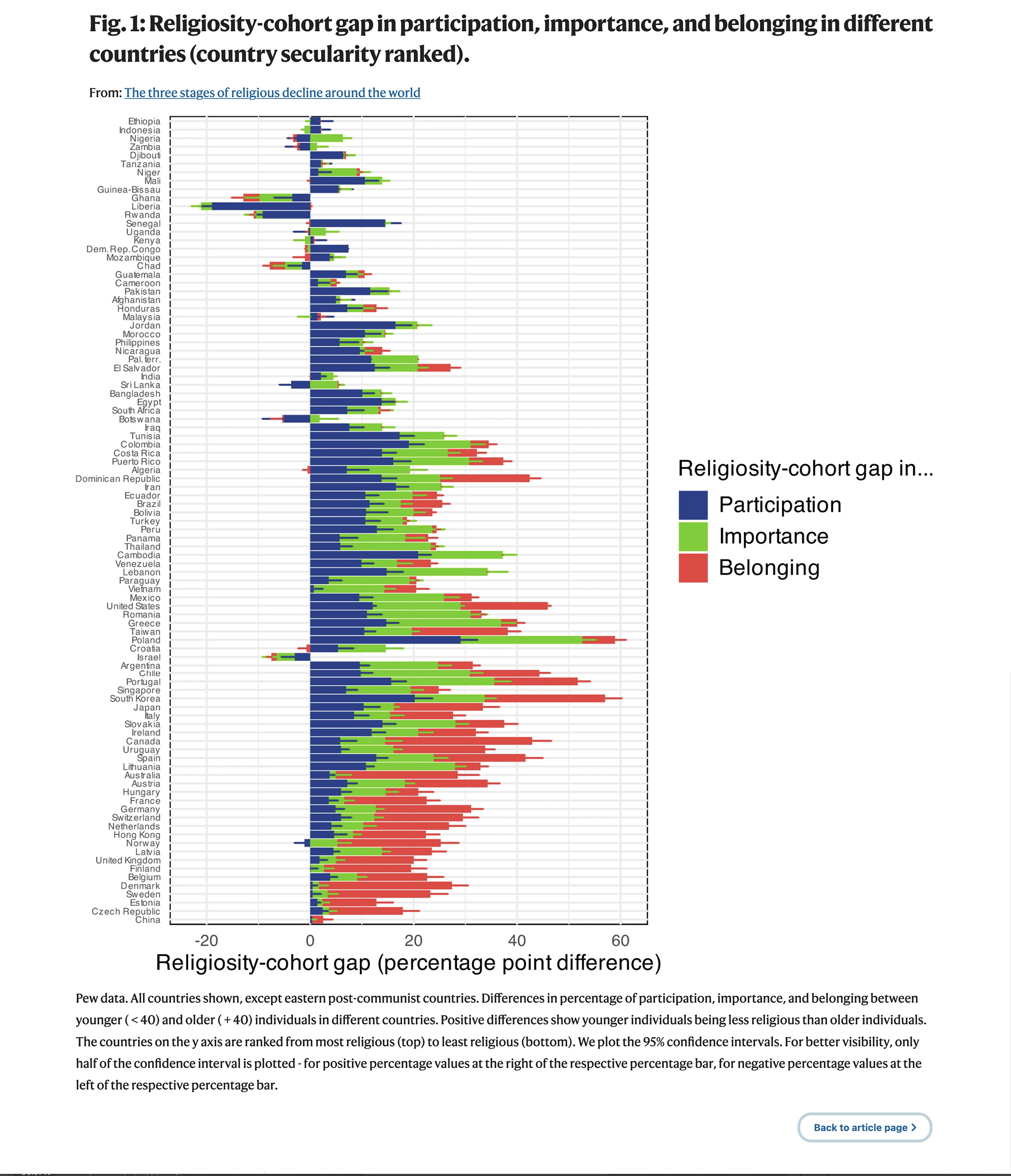

According to the study, countries around the world can be placed at different points along this secular transition. In much of Africa, religion remains a central part of daily life, with high levels of participation. Countries across the Americas, Asia and Oceania often fall in the middle range, where public participation and personal importance are already slipping, though formal belonging has not yet declined to the same extent. The United States is also in this middle range, with gaps showing up across all three measures.

Europe stands out as being the furthest along this path: The European countries included in the study are in either the middle or later stages of the P-I-B sequence — with both historical trends and current data supporting this trajectory.

The secular transition shows up across countries with Christian, Buddhist, Hindu and Muslim majorities. Although fewer Buddhist- and Hindu-majority countries are included in the data, early signs of the P-I-B sequence can still be observed in those contexts as well.

“We had questions that were tailored to the way people participate in religion in different traditions and parts of the world,” Hackett told RNS. For example, in East Asia, people usually don’t go to a place of worship on a weekly basis. “However, when we look at other kinds of belonging or participation, we still see generational gaps,” he said.

In Muslim-majority countries, the pattern appears to stall after the first two stages: Participation and importance may be dropping slightly, but people largely continue to identify with their religion.

“Religiosity-cohort gap in participation, importance, and belonging in different countries (country secularity ranked).” (Courtesy graphic)

The P-I-B sequence is most clearly visible in traditionally Christian countries, about which researchers had the most data among countries spanning the full range of the secular transition.

The authors, however, caution that the study covers only a few decades and that, in many regions, secularization is still in its early stages. They also note exceptions to the trend, including post-communist countries in Eastern Europe and Israel, where patterns of religious change diverge from the typical trajectory.

The findings are part of a larger intellectual tradition.

David Voas, a quantitative social scientist who developed the original secular transition theory, said the study helps to build a big-picture framework that explains global patterns. “To me, as somebody who is interested in religious change internationally, this is a global phenomenon that cries out for some kind of general analysis and explanation,” he told RNS.

Like the authors of the new study, Voas sees secularization as a component of modernization, which also includes the transition from agrarian to industrial and post-industrial societies. “When you look at the global situation and see that decline is happening around the world – it’s not restricted to just Christian countries, it’s been going on everywhere for a very long time – you realize this is not just something that is going to change because there’s a political or cultural shift in one or two places,” he said.

While other scholars focus on what is happening in individual contexts, Voas argued it is equally important to study the bigger picture. “It’s clear that religious decline is happening,” he said. “It’s not so clear why.”

Harvard Divinity School professor Gina Zurlo, who studies Christianity around the world, said the P-I-B model has a familiar ring for modern Christians in the West. “Attending religious services and engaging in other public practices is a commitment,” Zurlo said. “It requires time, energy, money, travel, leaving the house, gathering your kids, looking presentable, whatever. If you’re questioning faith in any way at all, why put in so much effort?”

But Zurlo suggested that the result may not necessarily be a decline as much as making religion a more private affair.

“Our hyperindividualistic society has essentially granted people permission to be religious in their own way. They can pray, believe in God, read Scripture and engage in other spiritual practices completely on their own — without ever stepping foot in a house of worship — and still be considered a religious person.”

Other scholars also cautioned that the story of religious adherence is more complex, pointing to cycles of change, cultural differences and new forms of spirituality that surveys and one global model may not capture.

Landon Schnabel, a professor at Cornell University who studies social change, inequality and religion, praised the study’s P-I-B model as “an important framework for understanding recent trends based on available survey data” but said it may not represent “longer-range cycles of religious change.”

Schnabel argued religious life doesn’t follow a straight line toward secularization. “We see it as a pendulum swinging between institutions and individuals, conformity and rebellion, building up and tearing down, and structure and spirit,” he said.

He also points out that people may be returning to forms of religion that aren’t contained in formal institutions. “For most of our species’ existence, spiritual practices were more localized, fluid and integrated into daily cultural life,” he explained. “Spiritual practices were embedded within the religion of particular peoples and places.”

What looks like a decline, he suggested, may be a return to spiritual engagement that is “more personalized, syncretic and centered on individual authority rather than institutional power.”

Kyama Mugambi, a world Christianity professor at Yale Divinity School, warned against analyzing demographic data through a Western lens. He said regions such as Africa and Latin America show different patterns of religious change. “Secularization, as construed in the study, is largely a Western construct,” Mugambi said. “Though it affects societies around the world, secularization will inevitably take different forms, shaped by the social, cultural and intellectual histories of the places it encounters.”

We should be cautious, Zurlo said, in assuming the end of religion everywhere in the world. “The world is a furiously religious place and, in my estimation, it will continue to be for a long time,” she said. “Religion changes constantly as societies modernize, technology advances, women gain more decision-making power, and as people reinvent what it means to be religious in their specific time and place.”

While scholars debate whether modernization leads to secularization and religious decline, or simply to new forms of religiosity, there is broad agreement that change is underway. The question is not if religion is shifting, but how to understand it.

For religious communities, the study may serve as a reminder that they are not alone in seeing fewer people in the pews or less interest among younger generations. Whether those trends signal lasting decline or emerging forms of faith, the findings suggest religious life everywhere is being reshaped in ways that demand attention.