(RNS) — A controversial exhibition of graffiti art opening Friday (Oct. 17) at one of Britain’s most famous medieval cathedrals has already attracted the ire of U.S. Vice President JD Vance and billionaire Elon Musk, both of whom called the show “ugly.”

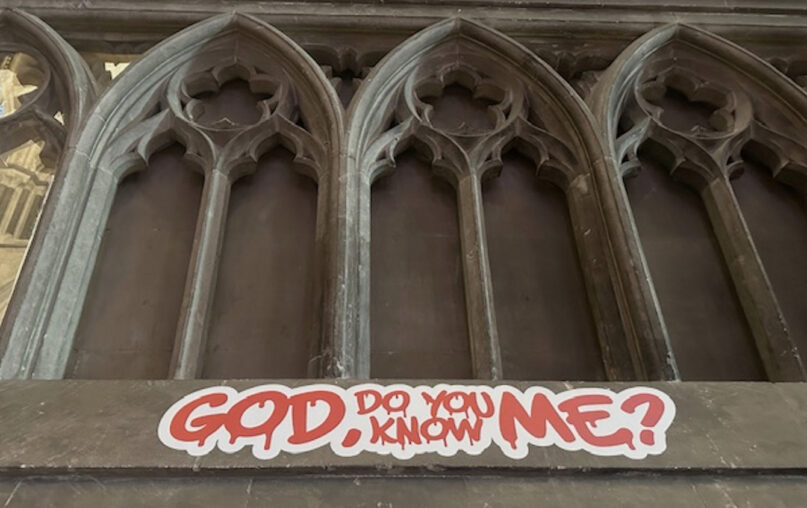

Called “Hear Us,” the exhibition at Canterbury Cathedral, the seat of the Church of England’s primate, has tagged the 11th-century building’s stones with graffiti in easily removable paints. Created by representatives of marginalized U.K. communities, the inscriptions contain messages to God such as “Why did you create hate when love is by far more powerful?” and “Are you there?”

Vance, writing on X after seeing details of the exhibition preview, said the installation “had made a beautiful building really ugly.” Musk reposted Vance’s comment with the words “really ugly.”

They weren’t alone. Canterbury’s decision to install contemporary graffiti has shocked many on social media, with some churchgoers calling it sacrilegious.

As the mother church of the Church of England and the wider Anglican Communion, Canterbury has attracted uncountable thousands of pilgrims since an earlier structure was built in 597. It gained further fame after Bishop Thomas Becket was martyred there in 1170. The appointment of the new archbishop of Canterbury, the Rt. Rev. Sarah Mullally, was announced at the cathedral a fortnight ago, and her installation will take place there in March.

While it is known throughout the Anglican Communion, many locals don’t feel the cathedral is a place for them, according to the exhibition’s curator, Jacquiline Creswell, and the graffiti exhibition is intended to invite more of Britain’s public into the sacred space. The artists featured are members of the Indian and Caribbean diaspora, neurodivergent and LGBTQIA+ groups.

Part of the “Hear Us” exhibition at Canterbury Cathedral in Canterbury, England. (Photo © Canterbury Cathedral)

The dean of the cathedral, the Very Rev. David Monteith, called graffiti “the language of the unheard,” noting that even as it is often “an act of vandalism, division or intimidation,” it can also furnish “a way for the powerless to challenge injustice or inequity.”

“We could easily have rendered the questions to God as medieval-style calligraphy,” said Monteith, “neatly hung on canvas within the cathedral, but they would likely have gone unnoticed and unremarked upon — with few, if any, choosing to engage with the questions of faith and meaning at their heart.

The graffiti is also part of a long tradition of graffiti in the cathedral. The artisans and construction crews who worked the vaulting Gothic building left their own marks, while simple crosses make evident the faith of pilgrims.

A team of volunteers has been surveying the historic graffiti in the cathedral as part of a project begun in 2018, and this autumn it will be running tours of the masons and pilgrims’ work.

According to the British Pilgrimage Trust, a charity that encourages pilgrimage in the U.K., the older graffiti in cathedrals is highly popular with visitors. “Pilgrim graffiti is a cherished part of sacred heritage and many churches and cathedrals around Britain,” said the trust’s co-founder Guy Hayward, “with crosses carved into walls and doorframes and stone altars by pilgrims setting off on their long journeys, with one straight line for when they leave and one line to complete the cross on their return.

Parts of the “Hear Us” exhibition at Canterbury Cathedral in Canterbury, England. (Photo © Canterbury Cathedral)

“When I show pilgrim crosses to visiting pilgrims they often get more excited than with the more standard objects, as it personalizes and gives heart to the whole practice of pilgrimage,” said Hayward.

But the dean has acknowledged that public opinion has been split over the modern graffiti’s appearance in the cathedral. “Seeing this graffiti imagery juxtaposed against the cathedral’s stonework – much of which is covered with centuries-old scrawled religious markings and historic graffiti – is undoubtedly jarring and will be unacceptable for some,” he said.

“But rather than react just on the basis of a few online comments,” he added, “I would encourage people to come and experience the artworks for themselves and to make up their own minds. Rather than be distracted by the aesthetics of the graffiti lettering, I hope that people will want to think deeply about the questions posed within the artworks and experience the sense of meaningful encounter that we want all who come to the cathedral to have.”

The exhibition is not the first time that English medieval cathedrals have resorted to unconventional installations to encourage visitors. In 2019, a spiral slide known as a helter skelter was installed inside Norwich Cathedral, which was finished in 1145, drawing criticism. The cathedral staff said it made the space more welcoming and less intimidating. The same year, Rochester Cathedral installed a nine-hole mini-golf course in its nave in an attempt to draw young people.

Another popular venture for cathedrals has been the “silent disco,” a dance party whose participants listen to the music on headphones. Canterbury has already held one, and others are coming up in Chelmsford and Durham, the latter a renowned medieval cathedral with its shrine to St. Cuthbert.

Part of the “Hear Us” exhibition at Canterbury Cathedral in Canterbury, England. (Photo © Canterbury Cathedral)

The Very Rev. Philip Plyming, dean of Durham, said, “We host a range of events throughout the year, in which we welcome people who would not otherwise come to church, and which raise revenue to maintain our Norman building for future generations to enjoy. Durham Cathedral is one of the only major cathedrals which does not charge an entry fee to visitors, and revenue raising events are an important way of enabling us to maintain this commitment.”

Plyming said the cathedral’s “daily rhythm of worship and prayer” was not disturbed by the events, adding, “we are clear that we are primarily a place of pilgrimage, prayer and proclamation.”

The latest statistics for Anglican cathedrals for 2024 showed weekly attendance rose to 31,900, an increase of 11% compared with 2023. Visitor numbers surpassed pre-pandemic levels for the first time in 2024, reaching 9.87 million.

A spokesman for the Association of English Cathedrals said its members “are doubly pleased to support all the cathedrals in their endeavors to play their part in engaging with their communities where they are, and being a space for all people of all faiths and none, in whatever way and for whatever reason, especially as we continue to consolidate and grow our visitor and worshipping numbers back after the challenges of the pandemic.”