RELATED: As the Feast of Our Lady of Guadalupe approaches, the Virgin Mary inspires community

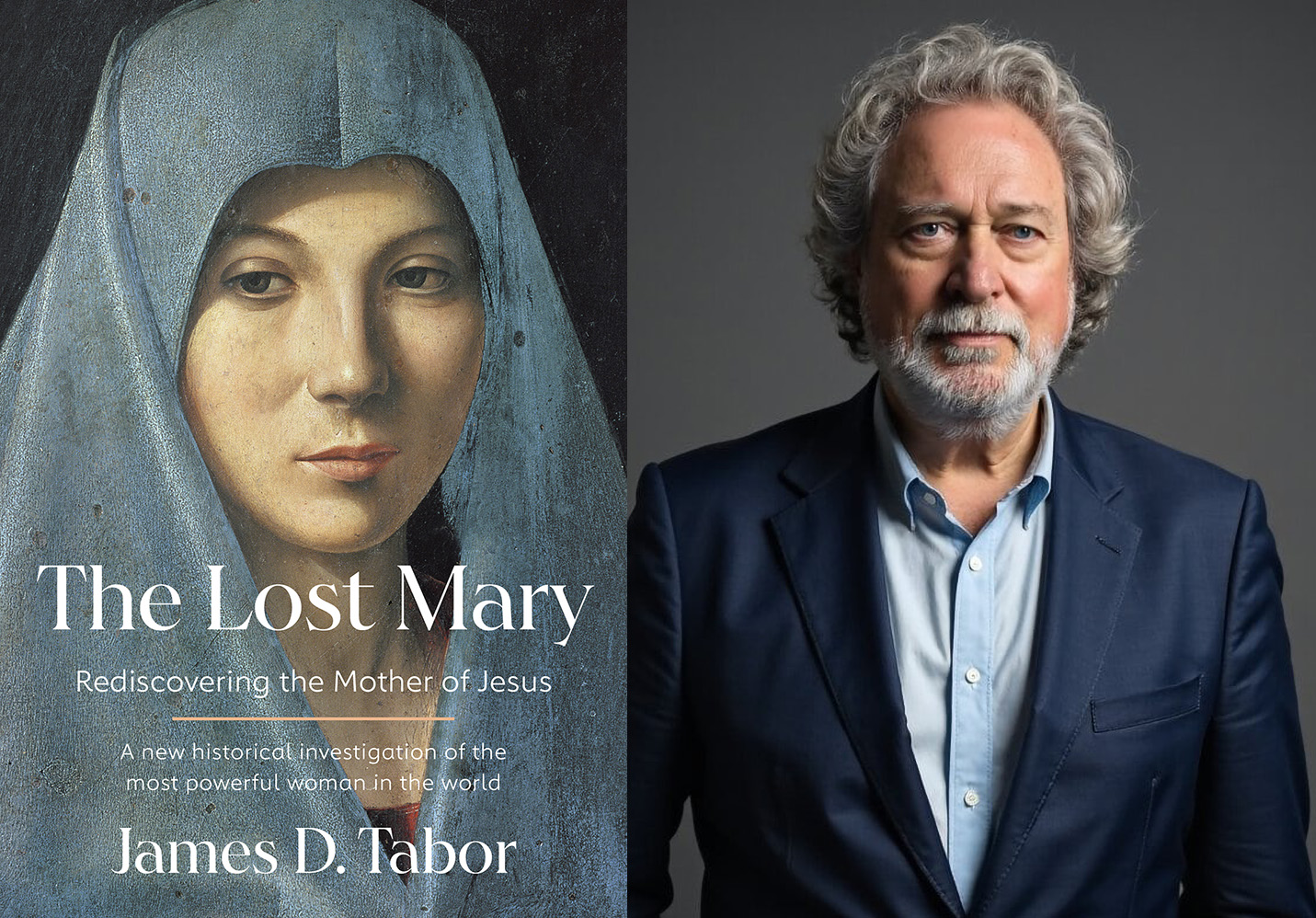

A researcher on early Christianity and the author of the 2006 New York Times bestseller “The Jesus Dynasty,” Tabor has dedicated his career to rehabilitating the lives of four figures who gravitated around Jesus: John the Baptist; James, who he argues is Jesus’ brother; Mary Magdalene; and Mary. A retired professor of religious studies at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, Tabor also taught at William & Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia, and the University of Notre Dame in Indiana.

“The Lost Mary” tries to capture both Mary as an ordinary Jewish woman and the extraordinary life she led, birthing a Messiah and influencing the movement her son led, the author said. He writes in the first chapter, “Mary was not just a vessel who brought Jesus into the world; she was a proud Jewish woman with a life of years of devoted motherhood and guidance. … Taken together and put into their historical contexts, we can lift the veil on the human Mary and catch unexpected glimpses that shatter our preconceptions and assumptions.”

Tabor’s research, built on dozens of trips to the Holy Land, analysis of early church historian accounts, the Bible and archaeological excavations, helped him find clues to what Mary’s life was like. The result, he said, offers Christians an occasion to connect with Mary on a more human level — though he insists he doesn’t want to desacralize her.

“Good historical research is not an enemy of sincere faith,” said Tabor, who resides in Charlotte. “It might be an enemy of dogmatic faith … but not someone who’s really seeking.”

In a chapter titled “The Forgotten City of Sepphoris,” the author describes what Mary’s teenage years witnessing the Romans’ repressions of Jewish revolts would have been like. In Sepphoris — a city in ancient central Galilee, now in Israel — Mary observed the Romans’ crucifixion campaign, a treatment reserved for self-proclaimed candidates to the Jewish throne. A woman of Davidic lineage, Mary also witnessed King Herod’s targeting of potential Jewish heirs, which probably shaped many of her life’s decisions, Tabor argues.

In a chapter called “Mary’s Secret,” the book weighs in on the numerous theories on the identity of Jesus’ father. Tabor examines one of the most popular, according to which, Mary would have met Tiberius Julius Abdes Pantera, a Roman soldier from Phoenicia, present-day Lebanon, deployed in Nazareth. Tabor, who rejects that interpretation, shares what he found visiting Pantera’s tombstone in Germany.

Though he acknowledges the identity of Jesus’ father remains unknown, and one of Mary’s numerous secrets he wants to “honor,” Tabor uses this chapter and parts of the book about Mary’s other children to debunk claims that Mary never had a sexuality. In Roman Catholic traditions, the children Mary raised are believed to be Jesus’ cousins, while the Orthodox Church believes they are the children of Joseph’s former marriage. He argues writings of second- and third-century theologians, which deny any sexuality to Mary, distorted her. “She is so holy, she’s so heavenly, that we lose her,” he said.

RELATED: The Punk Rock Spirit of the Virgin Mary

“The Lost Mary” also offers a glimpse of what Mary’s personality might have been like. The legacy of her son’s teachings offers clues on the education she gave Jesus and the type of woman she was, Tabor said.

In chapters dedicated to her life in Jerusalem, living in a house near the Old City’s Zion Gate — where the Abbey of the Dormition now stands — the book highlights how she tangibly influenced her son’s three-year ministry. The house, perched on Mount Zion, became the headquarters of the movement, even after Jesus’ death, when James took the reins, according to Tabor.

Where his research couldn’t elucidate certain answers, Tabor deliberately extrapolates to fill the gap in Mary’s story. When he attempts to describe Mary’s psychology vividly, Tabor also speculates on her thoughts.

“Someone could criticize the book and say, ‘You’re just imagining,'” he said. “And I would admit that, yes, I’m imagining. But I’m imagining based upon what we know of the times, the place and putting her in her place.”