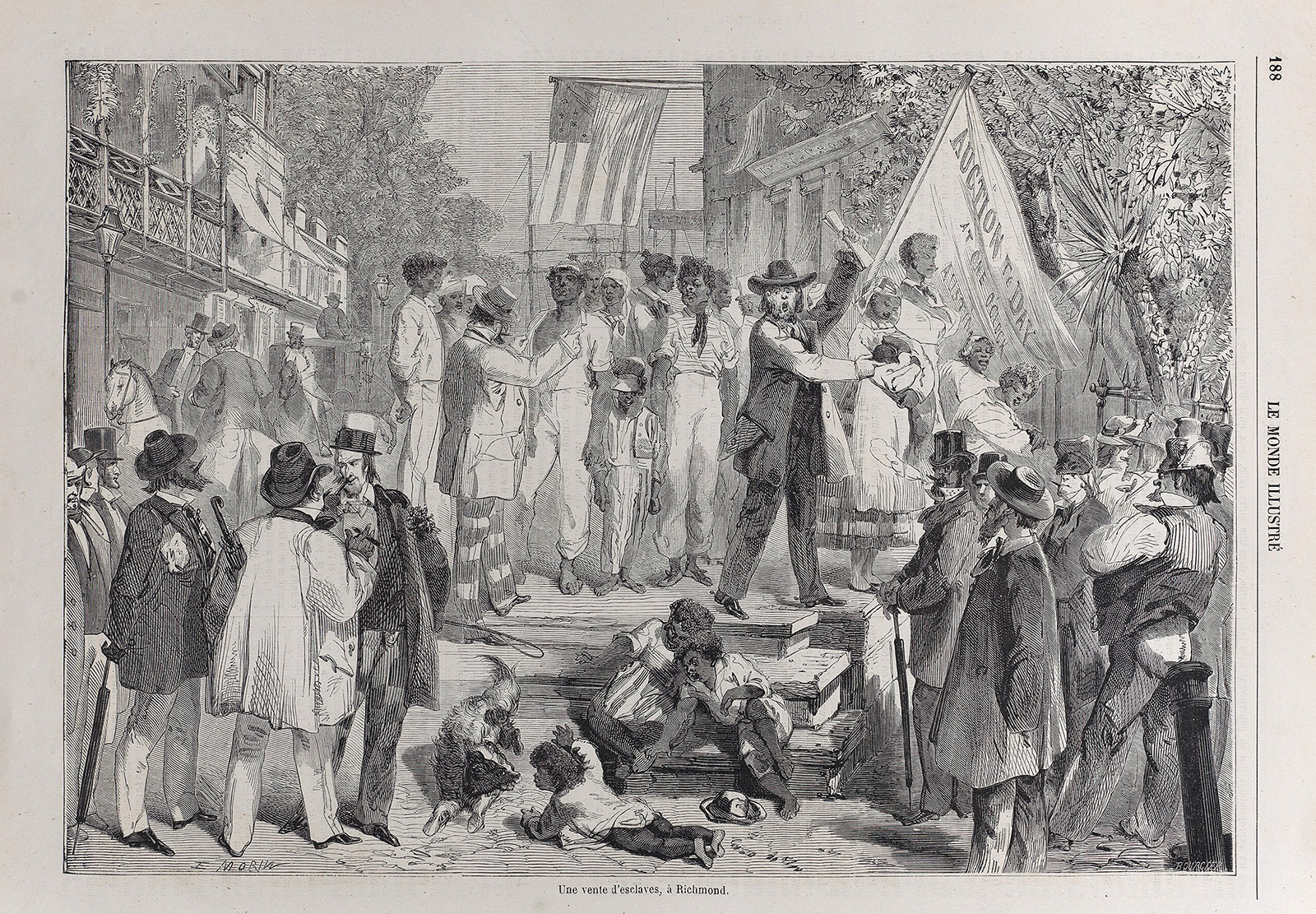

(RNS) — At the height of the anti-racism protests following the murder of George Floyd in 2020, the idea of reparations for Black Americans for the long shadow of slavery gained traction. State and city leaders, as well as religious leaders began to consider how to compensate those whose unpaid work had made them what they are today.

In Virginia, the Episcopal Church’s history of slavery made this quest especially significant. “I mean, it’s the state of the Confederacy,” said the Rev. Kelly Brown Douglas, a Harvard Divinity School professor who served on the neighboring Episcopal Diocese of Washington’s reparations committee. “If there is a diocese that could actually model and lead the way in this regard, it would be a diocese like that of Virginia.”

In 1860, some 82% of Episcopal clergy enslaved at least one other person in Virginia, according to the U.S. Census.

In 2021, the Virginia diocesan convention, the diocese’s governing body, voted to appoint a Racial Reparations Task Force, and to raise $10 million toward a reparations endowment. The resolution did not specify what form those reparations would take, but it said it “should be determined by and made to people directly affected” by chattel slavery and violence against Indigenous peoples.

Bishop Mark Stevenson. (Photo courtesy of the Episcopal Diocese of Virginia)

But nearly four years later, the Virginia church’s reparations effort has stalled, with no evidence that any of the $10 million has been raised. In March, Bishop Mark Stevenson abruptly dismissed the task force in a Zoom call, former members told Religion News Service, and the diocese has quietly missed goals once trumpeted as social justice wins.

Even as corporations have recently backed away from the diversity, equity and inclusion pledges, Episcopal Church leaders continue to embrace racial justice, even in its most controversial form of reparations. But the experience of Virginia, the denomination’s largest domestic diocese, shows that overcoming the practical challenges of reparations work — securing funds, agreeing on goals and unifying the diocese behind a plan — require more than a commitment to righting the wrongs of the past.

Though the Virginia diocese named a second task force with mostly new members last month, those who were dismissed are asking when and how the diocese will complete the resolution’s mandate, and some said they believe fading interest in racial justice work has contributed to the diocese’s struggle to deliver on its promise.

RNS’ reporting is based on interviews with former task force members and documents, including official meeting notes.

RELATED: New York’s Episcopal Diocese launches $1M racial reparations fund

The idea for a diocesan racial reparations fund began in 2020 through a group called “Good Trouble,” named after the late John Lewis’ description of his civil rights work, said Dennis Carter-Chand, a member of the group. In November 2021, the group, led by Rev. Cayce Ramey, offered a resolution to the diocesan convention, calling for the $10 million endowment. It recommended the funds be raised through the sale of diocesan properties valued at $19 million. Bishop Susan Goff appointed a 12-member task force in April 2022.

The resolution stated the endowment was to be established by the end of 2026, without specifying the duration of its members’ terms.

Similar efforts were underway elsewhere in the Episcopal Church. Then-Presiding Bishop Michael Curry, the first African American to lead the denomination, had overseen the creation of a coalition for racial equity and justice and launched an 11-part anti-racist curriculum. New York, Texas and Maryland dioceses had also launched racial justice committees and reparations commissions.

Carter-Chand, who has read deeply about the history of slavery in Virginia, eagerly applied when the diocese announced the initiative, he said, highlighting his involvement in his local church. But he also offered his experience as a person of color in predominantly white churches, which he believed would help Episcopalians reckon with their racist history. “We really wanted to engage the Episcopalians in Northern Virginia in a conversation about where we are now, why are we doing reparations and what the history is,” Carter-Chand said.

The idea felt like “a spirit moment,” said another former task force member who requested anonymity because of relationships in the diocese. “It was started imperfectly. It was started with hope.”

RELATED: A priest observed a ‘Eucharistic fast’ for racial justice. Now, he could be deposed.

Early on, the task force discussed ideas such as how to educate parishioners about how the diocese benefited economically from chattel slavery, Carter-Chand said. Their charge document called for its members to visit every region of the Diocese of Virginia and identify communities affected by the “biases born out of white supremacy and systemic racism,” including substandard housing, food deserts, sub-par education, lack of “fair wage” employment and lack of health care access.

Though it’s difficult to estimate the amount of wealth slaves’ labor brought, said Jennifer Oast, a colonial America historian at Pennsylvania’s Commonwealth University, there’s no doubt enslaved people significantly enriched the denomination. Soon after the first slaves arrived in 1619, leaders of the Church of England, which became the independent Episcopal Church after the American Revolution, started considering ways to use their labor to expand the church.

Under the leadership of the Rev. James Blair, a missionary from England, the church used slaves to compensate priests, administer schools and orphanages and to grow its tobacco business, Oast explained. “He had these ideas about how enslaved labor could build up the church, which was struggling in late 17th-century Virginia, mainly because they could not get educated ministers to come over to the colonies,” she said.

Print depicting what is now known as “Ancient Campus” at the College of William and Mary in Virginia before the 1859 fire that damaged the Wren Building, center. Visible on the left is the Brafferton and on the right is the President’s House. (Print by Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C., 1887)

At William & Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia, which Blair founded in 1693 to train ministers, slaves cultivated tobacco on college-owned lots. The profits funded scholarships for seminary students. Church officials also encouraged parishes to purchase slaves to work on glebe lands — farm lands at the disposal of priests — and include the profits in their compensation, Oast said.

RELATED: Episcopal Church apologizes for its role in slavery

That history was important, according to the task force, but the planned listening sessions in communities affected by the diocese’s history of white supremacy never took place. A few discouraged members left as a result, former members said.

Other members said they were dismayed by the diocese’s lack of progress on raising the $10 million endowment, which contributed to the belief the group was not fulfilling its mission.

Soon after the task force was formed, its finance committee suggested the sale of Truro Church in Fairfax as a funding stream. Truro, however, was occupied by a congregation that had broken with the Episcopal Church over LGBTQ issues 15 years earlier, joining the Anglican Church in North America.

After a five-year legal battle, a court ruled in 2012 that Truro’s property belonged to the Virginia Episcopal Diocese, but the diocese agreed to give Truro a rent-free lease in exchange for maintaining the property and for the use of part of the building. In 2020, after the diocese said it was in conversations with Truro leaders about selling the property, public backlash ensued. In a document evaluating financing options for reparations, the task force recognized Truro’s sale “could concern some in the Episcopal church.”

The discussions about selling Truro were cloaked in secrecy, with the property largely going unnamed in general discussion. Even some former task force members open to speaking about their frustration with the reparations process continued to heed the diocese’s warning about publicly naming the property and refused to answer questions about it.

Asked why the diocese chose not to sell Truro, the Rev. J. Lee Hill Jr., the diocese’s canon for racial justice and healing, said “there was no discussion of said church” at the January 2023 meeting. But task force members interviewed by RNS confirmed that the unnamed property discussed was Truro, and the meeting notes include a recommendation to sell a $10 million property that could cause “some tension because of the anti-LBGT-ordination stance of one potential buyer.”

The task force member who requested anonymity because of relationships in the diocese said it was clear “if Truro is not involved, we can’t reach $10 million through vacant property sales.” Nonetheless, task force members said the diocese repeatedly told them it was still in process of the Truro sale.

The diocese declined to explain how it plans to find the $10 million. Truro Church leadership did not respond to a request for comment.

Meanwhile, the task force was struggling to agree on what form reparations should take. “There are 12 members of (the task force), I believe, and there were 12 different understandings of what a healthy reparations piece of work would be,” said the Rev. Benjamin Campbell, a former task force member based in Richmond.

Campbell, who resigned from the task force because he got “fatigued with the lack of clarity,” said he first envisioned the initiative as a move to tackle structural issues in Black communities in and outside of the church. He attributed the group’s struggles to the complexity of that task. “You can’t do this stuff unless you’re clear about that there are very many different ways of looking at it,” he said.

The Rev. Benjamin Campbell preaches at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church on Aug. 18, 2024, in Richmond, Va. (Video screen grab)

Reparations have been approached differently by various Episcopal dioceses. Through a 2020 resolution at its diocesan convention stipulating $1 million in reparation funds, the Diocese of Maryland has allocated the money in four grant cycles to local organizations working to build up Black communities, including health care, affordable housing, environmental improvement, job creation and education projects.

The Rt. Rev. Eugene Sutton, Maryland’s Episcopal bishop from 2008 to 2024, said that, after 15 years of conversation about reparations, he was clear about his vision in order to move forward. His advice to other institutions — “There’s no perfect solution, but don’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good,” Sutton said. “At some point, somebody or some persons in authority have to make a decision and say, ‘This, we will do.’”

Since taking over from Goff, Stevenson, a former canon to Curry during his time as presiding bishop, has made a point of owning the topic of racial justice, and has strongly backed reparations in its rhetoric. “Confronting racism remains mission critical for me and for the Diocese of Virginia,” he wrote in July.

Stevenson declined to be interviewed, but wrote in an email that reparations work is rooted in the Episcopal Church’s Baptismal Covenant. It isn’t only about money, but also the “systematic unmasking of insidious practices that perpetuate inequality and injustice.”

Bishop Eugene Taylor Sutton, rear, offers a blessing over the work of the inaugural Diocese of Maryland reparations grants awardees, Thursday, May 26, 2022. (Photo via MarylandEpiscopalian.org)

But the transition to Stevenson’s leadership impacted the task force’s work, task force members said. When Goff, who had been contending with breast cancer, retired at the end of 2022, they said, they never got the support from Stevenson they were hoping for.

Attempts to reach Goff through her social media and the Diocese of Virginia were unsuccessful.

In the month leading up to the final meeting of the original task force, in March, the Virginia initiative already seemed to have hit a wall. “I felt like we were kind of misled as a task force in terms of level (of) engagement,” Carter-Chand said of the diocese’s efforts.

Speaking at a worship service in November 2024, Stevenson said the group had become too focused on money, according to several members. In his email to RNS, Stevenson said the work accomplished by the first task force “laid a strong and vital foundation,” but added that the diocesan leadership recognized “the need to reform and refresh the task force to focus on the next crucial phase of our work.”

The same day as the original task force was dismissed a call was put out to restart the initiative with a new committee. In mid-September, the diocese announced a slate of members that included two from the former task force. One former task force member, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to be candid while preserving relationships, said they noticed some of the more “forceful” members of the task force had not been reappointed to the new one.

“This didn’t feel routine at all. It felt rather abrupt,” said that member of the original task force. “I hope I’m wrong, but it feels like slowing down the process, rather than refreshing it.”

Asked why the initial task force was dismissed, Hill, the canon for racial justice and healing, said, “Refreshing committees and task forces happen regularly, as it is in line with best practices of both the church specifically, and nonprofits in general.” The diocese, he said, was still exploring “various options” to fund reparations, which could include “existing unoccupied diocesan real estate assets.”

Stevenson will release a full report about the fund in November, Hill added.

Some former task force members haven’t given up hope. One said, “My lament is that we weren’t able to move with the fierceness that the Spirit moment deserved. My hope is that the group is going to be able to build something beautiful.”

RELATED: $175,000 in reparations grants given by Episcopal Diocese of Maryland