(RNS) — From the days of Miriam, the sister of Moses and Aaron, Jewish women have been leaders-without-portfolio. In the Book of Exodus, Miriam, a “prophetess,” leads the Israelite women in song, but unlike Moses, the main recipient of teaching from God, and Aaron, the chief priest, she has no named role.

Today, women in many denominations of Judaism are able to attend institutions of higher learning to become equipped with the necessary skills to gain credentials to be called rabbi or cantor. What will they do with their newfound titles? A crop of new books and TV shows out this fall gives some answers.

Rabbi Léa Schmoll, the fictional subject of HBO’s new series “Reformed” (which is based on a book by Rabbi Delphine Horvilleur), is filled with doubts as she takes her first pulpit in her hometown of Strasbourg, France. The local Orthodox rabbi, Lea’s teacher and inspiration when she attended his classes as a child, visits at the behest of his congregants, but instead of discouraging her as they wish, he ends up telling her that she will be more valuable as a rabbi who has doubts than one with certainties: What she thinks of as a vulnerability, he says, can be a form of strength.

“We didn’t want the show to sound like Judaism has all the answers,” the producers of “Reformed” said in a recent interview.

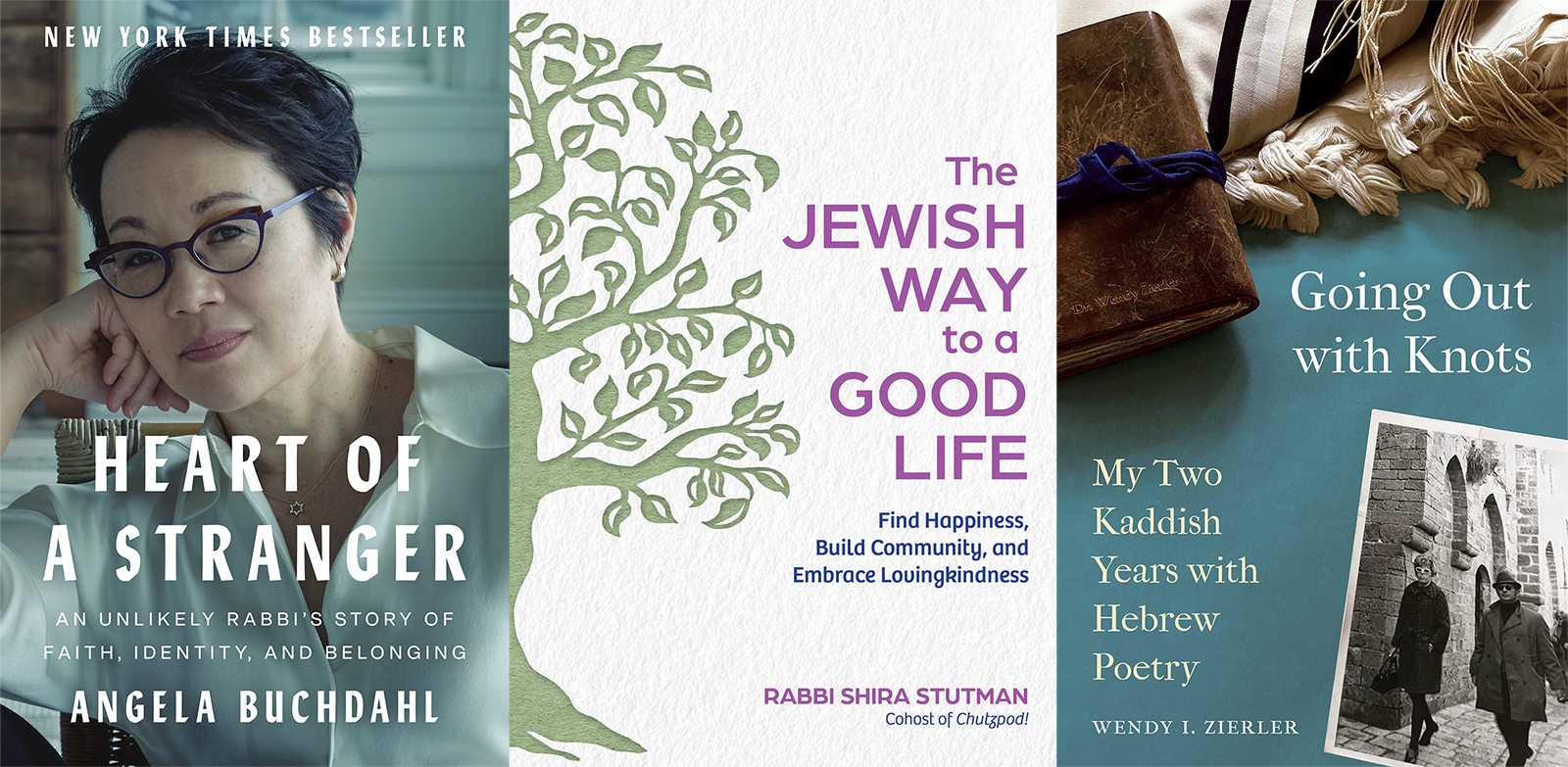

Women rarely feel as if they have sufficient answers, social scientists say, an attribute that may keep them from seeking leadership roles. In her new memoir, “Heart of a Stranger,” Rabbi Angela Buchdahl shows how this works. Born in Korea, where her parents met, she eventually becomes the fourth generation of her family to attend the Reform congregation that was founded by her father’s ancestors. After college at Yale University, then cantorial school and rabbinical school, Buchdahl finds her way to her first congregation, in New York’s northern suburbs, before being invited to the staff at Manhattan’s august Central Synagogue, where she began in 2006.

As in “Reformed,” the most affecting parts of Buchdahl’s book have to do with her doubts about her lack of qualifications, starting with her Jewishness. A summer spent in Israel with roommates who are more strictly observant “pegged me in my own mind as a counterfeit Jew,” she writes. Buchdahl calls her Buddhist mother from Jerusalem “using up five expensive long distance minutes in unintelligible heaves of crying” to say: “I’m not sure I want to be a Jew anymore. I don’t have a Jewish name; I don’t have a Jewish face. No one would even notice or care; I could just stop being Jewish right now.” Her mother responds, “Is that really possible, Angela?”

Today she leads a synagogue with 7,000 members, a $30 million endowment and 100 employees, and as the book makes evident, she is a skilled interpreter of sacred texts. Her early discouragement, and her ability to be honest about it, speaks volumes about what it means to be inside (or outside) a community. It also says a lot about how porous Judaism’s borders have become since Buchdahl was young, even as there are still some who don’t consider her a rabbi. Buchdahl writes, “Feeling like a stranger might be the most Jewish thing about me.”

Doubts aren’t the only obstacle for women looking to lead. The day Buchdahl had to decide whether to apply for Central Synagogue’s senior rabbi position, which she has held since 2014, she was also slated to appear on a panel with Anne-Marie Slaughter, on work-life balance, when her daughter ended up in the emergency room. With the help of a nanny, Buchdahl was able to be in the hospital and speak at the event, but she writes about the tension involved. The lessons the rabbi recounts, such as the value of a sparring partner who is willing to argue “in service of something bigger than themselves: getting closer to the truth,” are ones worth learning. That they are taught from a personal stance with a full measure of humility and honesty makes the book so much more accessible.

Not all female rabbis come from the same mold. In her new book, “The Jewish Way to a Good Life: Find Happiness, Build Community, and Embrace Lovingkindness,” Rabbi Shira Stutman, a co-host of the podcast “Chutzpod!,” has many answers, most of them rooted in Jewish sources and traditions. But this guide for the Jewish-curious often suffers from advice that’s obvious (“community doesn’t happen to you, community is something that you build and tend to, or it stagnates, withers, and sometimes dies”) or downright unhelpful: “The best way to think about queerness and Judaism in interaction is not as a problem at all, but as a thrilling opportunity.” Tell that to the queer Yeshiva University students who have fought for years to have their club approved and even won a lawsuit, yet are still blocked by the administration.

What’s most useful is Stutman’s point that Judaism’s answers don’t come just from rules and observances but embedded practices that result in community to share Shabbat dinner with or to help one another mourn. “The best we have to offer when sitting with a mourning friend or family member is not platitudes but presence,” she writes.

One promise of female rabbis is that they can add to the male-centric tradition by reflecting women’s unique perspectives. Rabbi Wendy Zierler, in her new memoir, “Going Out With Knots: My Two Kaddish Years with Hebrew Poetry,” isn’t shy about this point. “The feminist scholarly enterprise to which I had devoted my career,” she writes, “thus entailed three crucial parts: critical readings of male-authored canonical texts to expose this bias; the recovery of alternative feminine literary ‘herstories’ or traditions; and, if extant traditions didn’t suffice, the creation of something new.”

Zierler analyzes the contributions of poets Lea Goldberg, Rachel Morpurgo, Ruhama Weiss and Rachel Bluwstein, examining how these creative voices find their voices to remake a tradition given to them and also withheld. Only a trained literary scholar — Zierler has a Ph.D. in comparative literature from Princeton — and possessor of a rabbi’s knowledge of the Bible, Talmud and later Jewish texts and the prayerbook could explicate these writers’ allusions and wordplay and apply it to her own life, which has been difficult in recent years: She lost her father in a tragic accident, then her mother to illness, and cared for her mother-in-law, a Holocaust survivor, through her dementia.

Zierler uses poetry, in the words of Hebrew poet Yehuda Amichai, like a serum that courses through the veins to effect a cure for the dark times. She also relies on her love for the Jewish tradition, and Jewish community. Friends ask why she continues to attend an Orthodox synagogue, despite being excluded from the quorum of 10 Jews required for certain prayers. “Though I wasn’t counted in the minyan in a ritual or halakhic/legal sense,” she writes, “if I didn’t make it to shul on a given morning, I would get texts and emails from regulars, both men and women, asking me if everything was okay. If that isn’t ‘counting’ what is?”

Zierler is heartened by Ruhama Weiss’ “Chapters of the Mothers,” a poem playing against the Jewish text called the “Chapters of the Fathers” which opens with Moses handing down the Torah to Joshua and continues by relating the line of authority of patriarchs and male sages. Weiss summons a line of Biblical heroines: “from Hagar I learned to submit and/ afterward, to see/ And to find strength to save the boy,” referring to Ishmael, the son of Abraham.

The poem ends with a reference to the “Book of the Upright,” also known as the Book of Jasher, an alternative telling of the Bible that, Zierler writes, questions “the identity and comprehensiveness of this masculine tradition and pointing to its need for correction and amplification.” Zierler adds that “it was incumbent upon us to compose alternative texts and interpretations to supplement, affirm, and liberate.”

This confidence — to compose alternative texts and interpretations and incorporate them into the masculine tradition — is a culmination of the years of leadership-without-portfolio. It is nice to have TV shows about female rabbis, but books like Buchdahl’s and Zierler’s comfort us that there is substance and teaching from female rabbis as leaders beyond the flimsy image on a screen, and challenge us to transform the Jewish tradition into one that is fully inclusive and respectful of the lived vision and values of half its adherents.

(Beth Kissileff is author of the novel “Questioning Return” and co-editor of “Bound in the Bond of Life: Pittsburgh Writers Reflect on the Tree of Life Tragedy.” The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of RNS.)