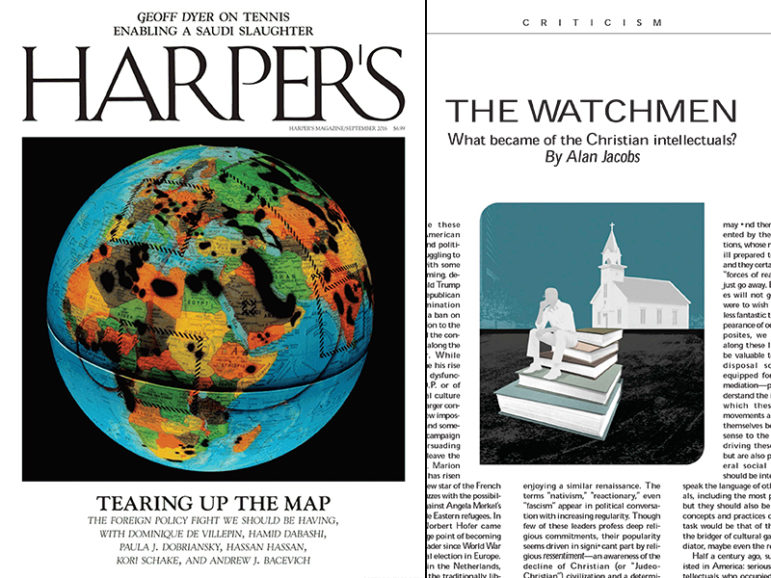

“The Watchmen” article by Alan Jacobs published in the September edition of Harper’s Magazine. Images courtesy of Harper’s Magazine

(RNS) In 1947 and 1948, respectively, Christian scholars C.S. Lewis and Reinhold Niebuhr appeared on the cover of Time magazine.

Since then, commentators have bemoaned the disappearance of the Christian intellectual.

Powerful social changes are behind the apparent decline: increasing pluralism, secularization, the decline of Protestant hegemony and the supposed triumph of science over faith as the best way to understand the modern world.

In the September issue of Harper’s, Baylor University professor Alan Jacobs dispenses with the standard explanations for why Christian thinkers are not considered authoritative voices in public debates.

Conservative evangelicals blame a hostile elite for forcibly excluding them from positions of cultural influence. Mainline Protestants posit a decades-long transition from being the public face of American religion to just another face in the crowd.

Jacobs’ very fine essay argues that the disappearance of the Christian intellectuals “isn’t a story of forced marginalization or public rejection at all. The Christian intellectuals chose to disappear.”

But here’s the truth: The Christian intellectual tradition is alive and well.

For those who want to engage age-old questions of meaning and values through the lenses of faith and reason, opportunities are practically endless. In every stream of American Christianity, believers are thoughtfully invigorating their faith through reading, writing, devotion and service.

Harvard theologian Ronald Thiemann, who died in 2012, challenged Christians not to long for “our Reinhold Niebuhr,” but rather to think more broadly about religion and the public intellectual. Modern men and women continue to perceive sacred value, even if outside the bounds of historic Christian institutions.

Whether inside or outside of church communities, the continued strength of religious publishing and the internet’s radical democratization of information offer broad access to a range of Christian thinkers who are intellectuals, if not scholars.

It’s true that the most famous Christians — megachurch pastors, evangelists and best-selling authors such as Rick Warren, Billy Graham and Max Lucado — do not write high-minded academic tomes. But believers of all stripes can find exemplary Christian intellectuals in their own traditions.

It’s said that American religion is 3,000 miles wide but only an inch deep. There is a strong anti-intellectual thread running through Christianity in this country, and the notion that a large audience clamored for the pronouncements of intellectuals like Lewis and Niebuhr is certainly a historical exception, if it is even true.

American Christians, especially in the most popular traditions, have looked with suspicion on highly educated co-religionists with ties to elite institutions. From pushback against 19th-century Unitarians and liberals who reconciled Christianity and science to today’s embrace of anti-intellectual political and religious figures, Christians might benefit from a more rigorous intellectual engagement with faith, even if they resist it.

Sure, Christians may revere intellectuals such as Augustine, Aquinas, Luther, Calvin and Wesley. But remember that Jesus, through whom God reconciled the world unto himself, was basically a layman. The central figure in human history held no advanced degrees.

Christianity, then, offers a corrective against the misplaced faith in science, expertise and technical progress that made the 20th century so dehumanizing and deadly — and may have created the expectation that Christians should be prominent public intellectuals in the first place.

Instead, conservatives congregated in institutions where they would not have to compete with secular ideas, while liberals tried too hard to blend in with fashionable academic and cultural elites.

We may not have Christian public intellectuals today, but we may not need them. With religion’s authority eroded and increased pluralism inevitable, neither presidents nor publics will seek the counsel of theologians any time soon.

This may be a blessing in disguise. The loudest Christian voices today are almost always among the least reflective. And popular success depends more on self-promotion, image and entrepreneurship than meeting widely agreed-upon standards of excellence.

It may be comforting to recall an era when middlebrow publications like Time and Reader’s Digest could assume a certain level of religious interest and literacy. But a movement that measures time in millennia should not be troubled that its leading thinkers have not been on magazine covers the last few decades.

Christians with intellectual gifts will be helping their brothers and sisters think through the great questions and challenges of their lives long past the end of Time. And maybe until the end of time.

(Jacob Lupfer is a contributing editor at RNS and a doctoral candidate in political science at Georgetown University)

The Christian intellectual tradition is alive and well

(RNS) So why have commentators bemoaned the absence of Christian thinkers as authoritative voices in American public debates?

“The Watchmen” article by Alan Jacobs published in the September edition of Harper’s Magazine. Images courtesy of Harper’s Magazine

(RNS) In 1947 and 1948, respectively, Christian scholars C.S. Lewis and Reinhold Niebuhr appeared on the cover of Time magazine.

Since then, commentators have bemoaned the disappearance of the Christian intellectual.

Powerful social changes are behind the apparent decline: increasing pluralism, secularization, the decline of Protestant hegemony and the supposed triumph of science over faith as the best way to understand the modern world.

In the September issue of Harper’s, Baylor University professor Alan Jacobs dispenses with the standard explanations for why Christian thinkers are not considered authoritative voices in public debates.

Conservative evangelicals blame a hostile elite for forcibly excluding them from positions of cultural influence. Mainline Protestants posit a decades-long transition from being the public face of American religion to just another face in the crowd.

Jacobs’ very fine essay argues that the disappearance of the Christian intellectuals “isn’t a story of forced marginalization or public rejection at all. The Christian intellectuals chose to disappear.”

But here’s the truth: The Christian intellectual tradition is alive and well.

For those who want to engage age-old questions of meaning and values through the lenses of faith and reason, opportunities are practically endless. In every stream of American Christianity, believers are thoughtfully invigorating their faith through reading, writing, devotion and service.

Harvard theologian Ronald Thiemann, who died in 2012, challenged Christians not to long for “our Reinhold Niebuhr,” but rather to think more broadly about religion and the public intellectual. Modern men and women continue to perceive sacred value, even if outside the bounds of historic Christian institutions.

Whether inside or outside of church communities, the continued strength of religious publishing and the internet’s radical democratization of information offer broad access to a range of Christian thinkers who are intellectuals, if not scholars.

It’s true that the most famous Christians — megachurch pastors, evangelists and best-selling authors such as Rick Warren, Billy Graham and Max Lucado — do not write high-minded academic tomes. But believers of all stripes can find exemplary Christian intellectuals in their own traditions.

It’s said that American religion is 3,000 miles wide but only an inch deep. There is a strong anti-intellectual thread running through Christianity in this country, and the notion that a large audience clamored for the pronouncements of intellectuals like Lewis and Niebuhr is certainly a historical exception, if it is even true.

American Christians, especially in the most popular traditions, have looked with suspicion on highly educated co-religionists with ties to elite institutions. From pushback against 19th-century Unitarians and liberals who reconciled Christianity and science to today’s embrace of anti-intellectual political and religious figures, Christians might benefit from a more rigorous intellectual engagement with faith, even if they resist it.

Sure, Christians may revere intellectuals such as Augustine, Aquinas, Luther, Calvin and Wesley. But remember that Jesus, through whom God reconciled the world unto himself, was basically a layman. The central figure in human history held no advanced degrees.

Christianity, then, offers a corrective against the misplaced faith in science, expertise and technical progress that made the 20th century so dehumanizing and deadly — and may have created the expectation that Christians should be prominent public intellectuals in the first place.

Instead, conservatives congregated in institutions where they would not have to compete with secular ideas, while liberals tried too hard to blend in with fashionable academic and cultural elites.

We may not have Christian public intellectuals today, but we may not need them. With religion’s authority eroded and increased pluralism inevitable, neither presidents nor publics will seek the counsel of theologians any time soon.

This may be a blessing in disguise. The loudest Christian voices today are almost always among the least reflective. And popular success depends more on self-promotion, image and entrepreneurship than meeting widely agreed-upon standards of excellence.

It may be comforting to recall an era when middlebrow publications like Time and Reader’s Digest could assume a certain level of religious interest and literacy. But a movement that measures time in millennia should not be troubled that its leading thinkers have not been on magazine covers the last few decades.

Christians with intellectual gifts will be helping their brothers and sisters think through the great questions and challenges of their lives long past the end of Time. And maybe until the end of time.

(Jacob Lupfer is a contributing editor at RNS and a doctoral candidate in political science at Georgetown University)

Donate to Support Independent Journalism!