(RNS) Sally Priesand was a 16-year-old Cleveland girl in 1963 when she wrote to the Reform Jewish movement’s flagship seminary and said she wanted to be a rabbi.

Hebrew Union College accepted her as the only woman in a class of 36, and in June 1972, Priesand became the first woman in history to be ordained by a rabbinic school. Today, all but Judaism’s Orthodox movement accept women rabbis, and non-Orthodox rabbinic schools typically enroll about as many women as men.

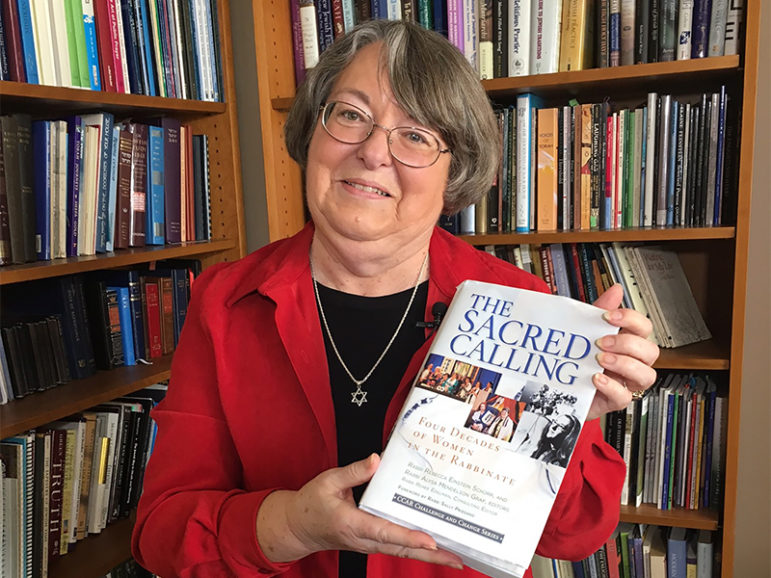

To mark more than 40 years of women in the rabbinate, the Central Conference of American Rabbis recently published “The Sacred Calling,” a collection of essays by women rabbis that cover everything from Priesand’s ordination to the depiction of female rabbis on television.

[ad number=“1”]

RNS asked Priesand, now 70 and retired for a decade, to talk about her ordination, her 25 years as the rabbi at New Jersey’s Monmouth Reform Temple and why she insisted on wearing miniskirts.

You say it was a “quirk” that you were the first woman ordained as a rabbi. Why “quirk”?

Sally Priesand as a rabbinical student, in her student pulpit in Jackson, Mich. Photo courtesy of the Jewish Women’s Archive

When I went to seminary there was one other woman in the program, and had she stayed, she would have been ordained before me. I didn’t really think very much about being the first. I didn’t do it to champion women’s rights. I just wanted to be a rabbi.

And I was in the right place at the right time. Dr. Nelson Glueck, the then-HUC president, wanted to ordain a woman. I was right on the cusp of the feminist movement. People were thinking of new roles for women.

How much sexism did you encounter at seminary and after ordination?

When I first came nobody really believed that I was going to finish. They thought I would marry a rabbi rather than be one. The professors were not really used to having a woman in class. They would always address the class as “gentlemen” and then they’d look at me and say “and lady.”

After four years of undergraduate school at Hebrew Union College I had enough credits to skip the first year of rabbinic school. So one day I was an undergraduate there and the next day I was in the second year of rabbinic school there, and everybody kind of woke up and said, “Oy, she’s still here!”

[ad number=“2”]

After I was ordained, some congregations wanted me for my publicity value and some congregations didn’t want me at all, and they made that very clear. In the end I got the best job, going to Stephen Wise Free Synagogue in New York City. I only got that because the position opened up late and everybody else had a job. I always say “coincidence is God’s way of being anonymous.”

You wore miniskirts in your early days as a rabbi. Were you trying to send a message?

The only message I was trying to send was “be yourself.” Miniskirts were very common then, and I had very long hair, down to my waist. I heard a lot of complaints.

Is there anything about your girlhood that might have predicted your ordination?

My family was not particularly observant but we did light Shabbat candles, have a Hanukkah celebration and a big Passover seder. And we belonged to a synagogue and went to services. The thing I liked most, which is probably the thing I still like most, is services.

I went to Jewish summer camp in Zionsville, Indiana. If you look back at my scrapbook from then, you can tell the campers and the counselors were well aware that I wanted to be a rabbi. I was fortunate because my synagogue allowed me during the summers to write articles for the bulletin and conduct services sometimes, and I tutored kids in Hebrew. I was very involved in Jewish life.

You thought you would be a married rabbi with children. Then you decided not to marry or have children. What made you change your mind?

The plan was to get married, to have children and to have a nursery next to my study in the synagogue. And everything was going to be great. But I knew myself well enough to come to understand that I could simply not have a career and a family at the same time and do both well. That doesn’t mean other women can’t do it.

The demands of family and the rabbinate are why, I think, you don’t see women as senior rabbis in congregations until they’re a little bit older. They’ve made other kinds of choices, which is fine. I certainly made my choice, and it was the right choice for me. I feel that all the children who grew up in Monmouth Reform Temple — they’re my children too.

Yet you were criticized in rabbinical school as “a true feminist.”

“The Sacred Calling” book. Photo courtesy of the Central Conference of American Rabbis

I wasn’t out giving speeches and marching and all of that. In my view you have to have women do that, but you also have to have women accomplish the goal and be the role model. So I tried to be the role model and be the rabbi. A feminist is a person who believes that every person, woman or man, should be allowed to develop their God-given potential.

Even though you didn’t want to be a pioneer, how did you assume the mantle?

It took me awhile to become conscious of being “a first.” After five years at Hebrew Union College, when it was time to find a student pulpit, the media found out about me and started to follow me around. And I’m a very private person. That’s the paradox of my personality, that I had to become so public. That was a difficult thing for me. Even ABC News did a documentary and followed me to class.

As a rabbi, you say one of the most important things you teach is for Jews to be responsible for their own Jewishness. What do you mean by that?

Rabbis are teachers and facilitators. They’re not meant to be surrogate Jews for the congregation. I teach that we should take one new mitzvah (acts required of Jews) at a time. I would make certain that I as the teacher would set the example.

One year I said I decided that during the holiday of Sukkot, I would eat dinner each night in the temple’s sukkah. And I invited everyone to pack a picnic basket and come and eat with me. That became a real tradition at our synagogue. Not only did we fulfill the mitzvah of sitting in the sukkah, but we got to just sit and casually get to know each other. I loved that. After a few years so many people would come that the synagogue’s brotherhood surprised me and built a larger sukkah.

[ad number=“3”]

I’ve been retired for 10 years and even today people come up to me and say: “One mitzvah at a time,” and they tell me how it has changed their lives. They started lighting Shabbat candles, or they started coming to services on Friday night.

What’s going to happen to women ordained in the Orthodox Jewish tradition given that movement’s refusal to recognize them? Or only accept them if they agree to titles other than “rabbi”?

It’s all going to work out. They’ve ordained almost about 15, I think, and they all have jobs someplace. I can see the Orthodox women are going through the same problems I went through, and I think it’s important to support them.

Regina Jonas, the first woman to be called “rabbi.” Her seminary refused to ordain her, so she was ordained privately by another rabbi in 1935. She died in Auschwitz in 1944. Photo courtesy of the Jewish Women’s Archive

You’d like more people to know about Regina Jonas, who was privately ordained in Nazi Germany in 1935. What should we know about this first woman to be called “rabbi”?

Her mentor died the year before she was to be ordained, and the seminary wouldn’t ordain her. So Rabbi Max Dienemann, head of the Liberal Rabbis Association of Offenbach, ordained her privately. At first she was only allowed to serve in homes for the elderly and schools. But as male rabbis began to emigrate or be deported, then they would turn to her and she developed a reputation for preaching.

In 1944 she was sent to Auschwitz, where we believe she died the day she arrived.

That day happened to be Shabbat Beresheit (the Sabbath when the first chapter of the Hebrew Bible is read). I am part of a campaign to get synagogues of all denominations, all over the world, to remember Regina Jonas on Shabbat Beresheit.