We had not meant to find ourselves in the midst of the Istanbul demonstrations, or thinking about tear gas. It just kind of happened.

I had come Turkey to lead two educational tours focused on the historical and spiritual dimensions of Turkey, when we found ourselves in the very midst of the Gezi Park and Taksim Square demonstrations. So I did what every responsible tour leader would do: I told my group to stay far away from Taksim if they are not comfortable with demonstrations, tear gas, and police riot. I gave them lots of alternate activities to do. Then I headed straight for Taksim, taking three brave souls along for the ride. The danger was not exaggerated: three of my friends had been hit by the tear gas: one had a canister hit her leg, another had a canister explode three feet from his head, and the third had extensive tear gas exposure.

In the days leading up, we had noticed how many aspects of the demonstrations were not covered (or at least fully covered) on some Turkish TV channels. Call it censorship, or whatever, it was obviously that many were turning to social media or obscure channels to get a sense of what was “really” happening. I even saw people living in apartments around Taksim Square getting on Facebook to ask what was going on just two blocks away from them, and which neighborhoods were exposed to tear gas.

We took the tram to the lovely little port of Karakoy, and then took the historic Tünel (second oldest underground train in the world) up to the middle of Istiklal street (“Independence Avenue”). The first thing that struck me was how “normal” everything looked. The images I had seen on social media from 48 hours earlier made Taksim look like a war zone, with barricades, tear gas canisters littering the ground, broken glass, and police riot running through the street. A few hours later, Istiklal and Taksim were bustling. Restaurants and shops were open, people were walking about going through their lives. It was another reminder of the need to not confuse life with social media. Social media is one reflection of reality, often with particular distortions or emphases. It was also a reminder of the quick recovery of the Turkish people after the devastations there a few days earlier.

One particularly egregious example had been when photos of the historic bridge connecting the Asian and European halves of Istanbul covered in a mass of humanity were circulated on social media as evidence of massive scale demonstrations that were harbinger of a forthcoming revolution. Well, it turned out that the photos were actually from the previous year’s marathon, not the demonstrations. Eventually, a few sites issued corrections, but not only many people had erroneously imagined the demonstrations to have been much more massive than they were.

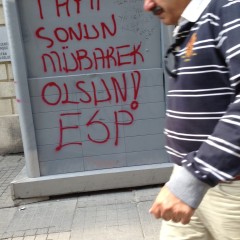

As we walked up Istiklal Street, we began to see some of the signs of what had taken place there. We started to see graffiti on the wall, many of which were directed against the person of Recep Tayyib Erdoğan, or the AKP-led government as a whole.

The signs were a mixture of amusing, inspiring, idealistic, and offensive. Most common ones called Erdoğan some variety of a Fascist. The Turkish word FASO (“Fascist”) was replaced with FA$O, with the $ (dollar sign) emphasizing the pro-capitalist policies of the AKP party. Here is one of the subtle mysteries of Turkish politics that many in the States have not properly understood: It is the Islamically leaning party (AKP) who are the Republicans in terms of their pro-business and pro-capitalism policies. It is the AKP party that has inaugurated many of the expansion projects for Istanbul, even as it has also tried to emphasize some of her Islamic past that it feels have been neglected, marginalized, and suppressed.

As we walked up Istiklal towards Taksim Square, the frequency of graffiti was increased, and so did the evidence of violence in the previous days. There were a few windows that remained broken and smashed. These are the thick protected glasses that would have taken some effort to break.

Broken glass remained on the streets. The tear gas canisters that had covered Istiklal, however, had been removed. To the best of our information, these were mainly American-made tear gas that had been sold to Turkey, another reminder of America’s role as the largest manufacture of both lethal and non-lethal weaponry in the world.

A few store signs were broken. The first few that we noticed were all multi-national corporations, like Starbucks (why on earth would the Turks, a people with one of the oldest and grandest coffee traditions need expensive and awful tasting coffee is beyond me), Burger King (again, why on earth would the Turks, a people with one of the ground meat traditions in the world need cheap meat sandwiches) and Pizza Hut. But it also showed that the violence was also random, as they also attacked some of the local establishments, like the pretty decent Bursa Kabob place on Istiklal.

That’s the thing about violence, eventually it ends up becoming all-consuming.

The graffiti evidenced the police’s brutal usage of tear gas on the protestors,

referring to Erdoğan as “Chemical Tayyib”,

a not so veiled reference to “Chemical Ali”, Saddam Hussein’s agent in charge of chemical gases.

The usage of tear gas was overwhelming, vile, and morally repugnant.

It was one of the common experiences talking with all the demonstrators:

who are these police who would use tear gas on us?

What are their values?

Who pays them to act like this?

Many of the demonstrators also developed a humorous attitude towards the riot police,

even holding up signs like “send the water tanks, we have not showered in three days.”

If there was one theme more persistent that hostility towards AKP (embodied by Erdoğan), it was speaking against police brutality. One particularly clever pun consisted of rephrasing the old name of Istanbul (Constantinople) to Constantino-Polis, with Polis being the Turkish for Police. Had Istanbul (Constantinople) become a Police-state?

There were signs of the disparate groupings there. One sign indicated the women’s peace organization. Another documented the presence of gay and lesbian groups, though indicating some resistance to their presence as well by stating: “We do not want a homophobic revolution.” Another indicated the anti-religious tone of some participants “Do not be a true believer.” As we would see in Gezi Park, the demonstrators were more of a coalition than one united party.

Walking up Istiklal to Taksim Square, we passed by a few small demonstrations. At one point when the police appeared too menacing, we ducked into the oasis of St. Antonio Catholic Church, built in the early 1906. Inside the serenity of the church seemed like a world away from the tension outside, though we knew that the religious spaces were not always sanctuaries. The Dolmabahche Mosque had been turned into a make-shift hospital a few days earlier to take care of the injured demonstrators, but even there the riot police had beaten up demonstrators and shot tear gas into the courtyard of the mosque.

A portion of the initial demonstration was motivated by environmentalist groups who objected to the tearing down of Gezi Park, a medium sized park with a few hundred trees adjacent to Taksim Square. As is the case with many symbolic places of resistance, the place was also exposed to some exaggeration. No, Gezi Park is not Central Park. No, Gezi park does not have 1.5 million trees, or even 1500 trees. But yes, it is one of the green spaces in this part of Istanbul. (Other parts of Istanbul have many other parks and green spaces.)

It is by now well known that the initial demonstrations were an anti- capitalist environmental one, by about a hundred demonstrators who did not want the park torn down as part of a Taksim Square renovation project. There have been conflicting reports about what exactly would be done when the Park is torn down, but rumors consisted of a new shopping plaza, possibly some hotels, and some replacement trees. The city authorities had done a particularly poor job of communicating their decisions to the public, or for that matter soliciting public opinion. Equally important had been the plan to direct all car traffic underground, and make the whole Taksim Square into walking plaza. These are images that the chief advisor to the Prime minister had shared with me, and if the eventual plans do end up reflecting them, it is not exactly akin to placing a Walmart in the middle of Central Park, as some had stated.

The real cause of the tension was elsewhere: a combination of sense of alienation among the demonstrators, out of line police brutality, and mismanagement of the crisis by the Turkish authority. This sign seemed to sum up the universal frustration with riot police:

ACAB “All Cops are Bastards.”

Every place is Gezi (Park).

Walking up to Taksim Square, we were greeted by a festive scene awash in people, flags, street vendors, and people selling water, watermelon, and more. Irony was also not missing from the square: The initial demonstrations had a strong anti-Capitalist tone to them. Of course when you have a few thousand people gathering in a square, capitalist motivation is not far beyond. There were vendors selling Che Guevara T-shirts, nationalist Turkish flags, etc.

We eventually made our way through the thick crowd to Gezi Park, and were greetings by a scene out of the 60’s. There have been a lot of commentaries trying to compare Gezi Park and Takism Square demonstrations to Tahrir square. This is not the “Turkish Spring”—at least not yet. In many ways, it is much more a kin to the Occupy movement. It’s much more diffuse, coalition based, alternative, disorganized, chaotic, young. And yes, it is true that many of these groups are motivated by a deep frustration towards the AKP party, and focus that frustration on the strong (to his supporters) or bombastic (to his detractors) personality of PM Erdoğan.

In the interest of full and transparent self-disclosure, my own leanings are that of a critic of global capitalism as being unsustainable, with a deep and abiding love for Turkey and her Islamic heritage, as well as the remarkable legacy of humanity living together here far better than we have elsewhere.

Even at that time, the remnant of the tear gas started to burn my face, especially the area around my nose and eyes. Another one of my friends who was with me shared that she was having a hard time breathing at time, like an asthma symptom. We consulted, but none of us wanted to turn back.

It seems good to make a few observations from the ground at Gezi Park:

1) This is more Occupy than Tahrir.

Some of the signs that we saw did try to make the connection between Tahrir and Taksim explicit: “Tayip may your end be Mubarak.” It is a clever pun, meaning may your regime end like [The ousted Egyptian dictator, Hosni] Mubarak, as well as meaning “Tayyip (Erdoğan) may your end be “blessed” (Mubarak)”.

A ton of media outlets are desperately trying to peg this as the start of the “Turkish Spring.” It is not, at least not yet, and perhaps we should be grateful for that. While there have been more or less positive results in Tunisia and possibly Libya, Egypt remains murky in many ways, and Syria is a human rights catastrophe. Perhaps we need less “springs” and more indigenous transformations. Erdoğan himself has astutely seized on the role of “foreign agents” in these provocations. Given Turkey’s role as one of the only forceful critics of Israeli policy in the region, it is tempting for many Turks to see these tensions as yet another way in which Neo-conservative factions would like to see yet another Muslim country succumb to in-fighting. One hears many similar discussions about advocates of Neoliberal capitalism vis-à-vis. I don’t dismiss such possibilities, but at the moment this does feel like a more internal Turkish issue.

The analogy with Tahrir Square also doesn’t fit. Tahrir threw out a ruler [Hosni Mubarak] who had ruled in a dictatorial fashion for 30 years. That description simply does not fit Erdoğan. His party has been elected three times, not with the laughable 99% results that we see in some places, but with solid 50% majority. Turkey is actually a fairly well-functioning democracy with the type of multi-party system that encourages dialogue and coalition building, unlike America’s own broken two-party system. Turkey has struggled in many key areas, in particular the treatment of journalists and freedom of press. But in many other key areas, it is years ahead of any other Middle Eastern society, including Israel. No, this is not Tahrir. It’s more akin to Occupy Movement.

The scene at Gezi park could have been Zuccotti Park: Men and women dancing, banging on drums, laying out in the sun, making astute critiques of neoliberal capitalism, and making political art. In certain corners the smell of something that still burned the eyes (maybe tear gas?) was mixed with cigarettes and marijuana. The majority of the participants were young, perhaps under 30, with a few who looked like they had been on a long, strange trip since the 60s.

Except imagine an occupy Movement where the neighborhoods surrounding Zuccoti park had opened their homes to them. This is exactly what many around Gezi Park have done and are doing. They are listing their homes addresses and phone numbers on Twitter, so that they can come for food. Many old women are cooking food and sending it to Gezi. There are even supermarkets which are opening up their offerings to people in Gezi for free.

There is a strong populist theme, as the sign to the right indicates: “The government must resign, power to the people!”

It is not, alas, a utopia. Interestingly enough, there were almost no Hijabi women in the crowd of a few thousand. This was somewhat startling, and even disturbing, to my eyes, simply because of the changing patterns of head-covering worn by many Istanbul women. Of course the Taksim and Beyoğlu areas are far from the neighborhoods like Fatih were the majority of women do wear hijab, but to see a crowd with almost no hijabi women was a bit odd. Later on I checked with some of my friends who are Muslim activists, committed women active on human rights issues who do wear hijab, and they confirmed my suspicions. The crowd at Gezi Park has been a hostile place for many Hijabi women. My friends did report that some of them had been harassed and assaulted by the demonstrators. Sadly, at least some demonstrators did not seem to grasp that the freedoms they were demonstrating for had to also be extended to their hijab-wearing neighbors as well.

2) There is a lot of political opportunism.

The young people’s gatherings (and they are overwhelmingly young) at Gezi Park seems beautiful, idyllic, not particularly organized, and Occupy-ish. Like Occupy, they are incredibly adept at using social media, and there are hundreds of graffiti marks with hash tags. Interestingly enough, some of the businesses on Istiklal that had tried to come to the aid of the demonstrators say that their only real challenge was finding enough plugs for all the folks who wanted to recharge.

There seems to be a distinct lack of hierarchy, instead being a large gathering of different interest groups from theater groups, socialist and Marxist groups, anarchists, and anti-capitalist Muslim organizations. That has not kept different Turkish political factions to attempt to coopt the movement.

Erdoğan’s AKP (Justice and Development party) is opposed by CHP (the Cumhuriyet Halk Partisi, the Republican People’s Party), which is in many ways a secular socialist/Kemalist group. The CHP has seized on the Gezi Park issue to raise support for its position, in particular through the actions of Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu. The CHP leaders have been hammering away at the AKP, but have conveniently neglected to mention that their own representatives voted to support the cutting down of the trees and putting up of the complex on Gezi Park.

This is one of the more unresolved aspects of the whole Gezi Park issue. Istanbul’s challenges of population growth are real: in a matter of two generations, a city of 3-4 million has mushroomed to around 15 million, and traffic issues are among the most real challenges facing this magical city. Even the AKP’s critics admit that they tend to be efficient, and get many large projects done. Ironically, it is their very experience with large business (and yes, indeed capitalism) that has allowed them to undertake these massive renovation projects, metro projects, large highways, etc. When they had proposed diverting car traffic under Taksim Square, the city councils in charge of approving it had done so unanimously, including the CHP opposition. Now sensing a political opportunity, the same party that had voted to approve the project had now turned against the AKP.

This seems to be one of the key challenges facing the demonstrators: how to avoid playing within the current coalition based system of Turkish politics, and instead advocate a higher form of accountability, visibility, and civic engagement.

3) Police Brutality is real.

Speaking with people in Gezi Park and around Taksim tells the same story again and again. Here is a brief overview.

The story is of disproportionate, random, and brutal police violence. Riot police beating down on defenseless protestors without provocation. The iconic moment of the protests so far has been the “lady in red”, an elegant woman named Ceyda Sungar in a summer dress who walking by Takism Square when was sprayed with tear gas that sent her curly hair flying up.

Ceyda herself, a Turkish academic, has refused to make herself the center of attention, instead preferring to focus attention on the shared experience of all Turkish citizens:

“Every citizen defending their urban rights,

every worker defending their human rights,

and every student defending university rights has witnessed

the police violence I experience.”

While Ceyda herself has tried to shy away from being the center of attention,

her likeness has been used by countless social media users as an avatar or profile picture.

Social transformations, particularly in this age, need icons and images.

Willing or unwilling, people are propelled into these roles where they express the ambitions and frustrations of the masses.

4) It’s about public space and democracy, not just trees anymore.

Taksim is a powerful symbol, because it is a reminder of the way that the public space is central to democracy. It is a place that people can gather, mobilize, see, speak, and be heard. Visibility is power. Taksim grows out of Turkey’s grand modernist experiment, complete with Ataturk statues and the Ataturk Cultural Center, high priced hotels, and the maze of streets and residential neighborhoods.

This is one issue that the demonstrators and the AKP can actually agree on: democracy is about more than votes and voting. It is about a civil process of negotiating rights and responsibilities in a public space. Both the AKP and the demonstrators agree that it is ultimately about having a real, vibrant democracy. Which is why these demonstrations are not (just) about trees anymore. Even the Turkish President,Abdullah Gul, conceded this when he acknowledged the impact of the demonstrations:

“Democracy is not just about voting [someone into power];

the message [the protesters want to convey] has been received. What is necessary will be done.”

The Gezi demonstrations might have started about trees, but they are no longer (primarily) about trees. They have spread all over Turkey, including conservative cities that have been the base of the AKP. At this point, it is more about a sense of not being represented, of not mattering, not being part of the vision of the AKP. That is in many ways the unifying feature of so many of the groups taking part in the demonstrations and the Gezi park sit in: The gay and lesbian groups, the women’s peace organizations, the secular groups, even the anti-capitalist Muslim organizations who do not support Erdoğan’s pro-business, pro-capitalism view of Islam. In that light, Gezi park today-and the waive of protests it has spawned—are about bringing out into full visibility the many other groups that do not fit, or feel that they do not fit, into Erdoğan’s view of Turkey.

I remember walking around Gezi Park, and seeing a young man in a hammock, tents pitched, lovers asleep on the grass. In another corner I saw a couple sitting on some steps, sucking on lollipops, giggling to one another. There was something innocent, even child-like about them. I thought back to Erdoğan’s description of the demonstrators as çapulcu (“looters.”) Erdoğan stated:

We cannot just watch some çapulcu inciting our people. […] Yes, we will also build a mosque. I do not need permission for this; neither from the head of the Republican People’s Party (CHP) nor from a few çapulcu. I took permission from the fifty percent of the citizens who elected us as the governing party.

It reminded me of Ahmadinejad’s dismissive remarks towards the Green movement participants as “khas o khashak” (“dirt and dust”). As had been the case in Iran, the participants reframed the insult as a self-designation, and now “Chapulling/ Çapuling” has become a popular social media status. There are even melodies along the lines of LMFAO’s “Everyday I am shuffling” that sing “Everyday I am Chapulling/ Çapuling.”

5) This is not simply Islamists vs. Secularists.

It is tempting to see this as a struggle of Islamicly leaning AKP against secularists. And that would be a mistake.

The AKP is not the Muslim Brotherhood, and Erdoğan is not Mubarak.

We have already noted the presence of various groups from anarchists and Marxists to anti-capitalist Muslims in Gezi Park.

One indication of Gezi Park not being the haven of secularists

was the way in which to honor the Prophet Muhammad’s heavenly ascension,

many of the folks there passed out special simit “kandil simidi” (sesame bagels)

made for this occasion.

So no, this is not a struggle between Islamists vs. Secularists.

It is much more subtle and complex than that.

There were many tender moments that had to be seen to be believed.

At another point a man held up a microphone for the Friday prayer leader.

If there is a hope for Turkey, it is in scenes like this,

for those of various ethics and commitment to realize that their own fate is tied up together.

This was not an isolated episode.

At one point during a rain, a member of the young atheist association held an umbrella over praying men.

One does not need to be praying to show compassion.

A tender sign was this one, during the Mi’raj (heavenly ascension) ceremony.

“No alcohol, no fighting, no bad words, no provocation, no violence.

Yes to respect, peace, prayer, protest and kandil simidi (the sesame bagel for the holy night).”

Yes, many of the protestors are rebelling what they see as Erdoğan’s paternalistic policies, such as the increasing restrictions being placed on serving alcohol between 10 pm and 6 am in certain establishments. Yes, there was one small march of people demonstrating with beer cans to protest Erdoğan’s policies. Turkey is a complex place, indeed.

Here is the great challenge of Erdoğan, and any ruling party in Turkey. Erdoğan has been the undisputed leader of the AKP, but he does not only represent Islamicly leaning Turks. He is the prime minister, and as the Prophetic hadith says, “the leader of the people is their servant.” Prime Minister Erdoğan does not need my advise, but if I were to offer him a word it would be that this is not a time to emphasize his 50% mandate, but rather this responsibility to represent and lead all the Turkish citizens. For all the shortcomings of President Obama (Guantanamo, Palestine/Israel, spying on American citizens, etc.), it’s time for Erdoğan to pull an Obama: “I don’t want to pit Red America against Blue America. I want to be President of the United States of America.” Likewise, Erdoğan’s challenge is to not rule as the AKP Prime Minister, but as the Prime Minister of all Turkish citizens.

This is the dilemma that Erdoğan and Turkey find themselves in: Erdoğan’s greatest asset is also his liability at this moment. He is a proud man, a strong leader, and a visionary who has been able to lead Turkey to becoming a regional leader and a genuine model that other Muslim majority societies look up to as a vibrant economical, political, and civilizational model. At this moment, his proud nature, even bombastic nature, is also serving as a handicap. Turks (and Muslims worldwide) admired Erdoğan for his confrontation with the Israeli president Shimon Peres in Davos, immortalized in the “One Minute” moment. But now is not the time for a “one minute” walk out. It is time for healing, for listening, for apologizing for heavy-handedness, and for bringing together. Erdoğan has been among the most powerful Turkish politicians of the Republican period. He should be wise enough to realize that he is not facing an Israeli adversary. He is facing his own people. He is facing a substantial percentage of his own society who right now do not feel represented, included, seen, heard, and accounted for.

At this point the key source of tensions with the government has been that of police brutality. Key members of the AKP have recognized that they have gone too far, and in fact the Deputy Prime Minister, Bülent Arınç,has already apologized for the “excessive force used by police.” It is good to hear from the Deputy Prime Minister, but the people want to hear from the Prime Minister himself.

As for the people in Gezi park, they have already achieved an improbably victory. They have realized that the people have power, that there are many in Turkey who are currently left out of the decision-making process, and that by bonding together they can flex their political muscle. The Mayor of Istanbul, Kadir Topbaş, has already conceded that no shopping mall will be built in place of Gezi Park.

Their challenge is in resisting the politics of nihilism, and also avoiding the tranquilizing drug of violence. The nonviolent demonstrations of the initial waive were mired by the violent and destructive behavior of some of the participants who destroyed side walks, private property, and smashed windows. The effects of the destruction have already been heard. On the Monday of the demonstrations, the Turkish stock market lost some 10% of its value, its largest drop since the illegal American invasion of Iraq in 2003. What remains to be seen is whether the large and powerful Public Workers’ Union Confederation (KESK) and its 240,000 members will join the demonstrations permanently. Nervously watching are members of the tourism industry, who have seen as many as 30% of the hotel reservations being canceled.

The Turkish Elephant

I began by mentioning that we were in Turkey for an educational tour. The focus of the tour is the multiple religious traditions in Turkey, with a special focus on the spiritual dimension of Islam, Sufism. The Sufi path has been a key component of Turkish culture, from the incomparable Mawlana Rumi to the poetic tradition of Yunus Emre, to the daily model of “adab” (lived kindness, generous selfishness) that is one of the hallmarks of many Muslim cultures. In Rumi’s masterpiece, the Masnavi, we read about a wonderful story that Rumi and other Muslim mystics had adapted from earlier Indian wisdom traditions.

One day an elephant wandered into the city of blind people. The folks walked up to the elephant, and began feeling the creature, and describing it. One of them felt the massive legs, and said that it was round, like a column. One felt the underbelly, and said it was flat and tough, like a wool carpet. One felt the ivory tusk, and said it was smooth. One felt the trunk and said it was like a massive snake. Another felt the tail and said it was like a rope. They were all right, and they were all partial. It was the ability to synthesize together these experiences that would help them figure out the creature that transcended any one person’s description.

Mawlana Rumi was describing God and the sacred, reminding us that each of us has a partial experience, and that the reality (haqiqa) transcends any one person’s experience and description. It also seems to me that the same description applies to Turkey—and by extension, any of our modern societies. The Turkey that Erdoğan and the AKP feel at home in, that of an Islamic-ly leaning society open to international trade, that Turkey is Turkey, but it is not the whole Turkey. The Turkey of the artists and bohemians in Gezi Park is Turkey, but it is not the whole Turkey. The Turkey of the anti-capitalist Muslim organizations also in Gezi Park is also Turkey, but not the whole Turkey. The Turkey of the night clubs and people marching for their right to drink and party is also Turkey, but not the whole Turkey. To see all of Turkey, the whole Turkey, requires to be able to synthesize all these different experiences. That is the challenge of unity.

I often tell my friends who join me in Turkey that Turkey is the bride with the thousand faces. She’ll be whatever you want it to be. You can walk some of the most exquisite mosques in the world, and learn from the most beautiful living Sufi masters. You can walk in the footsteps of St. Paul, and visit synagogues that were started before the time of Christ. You can walk down neighborhoods that would rival anything in the French Riviera, and islands that are as beautiful as the famed Greek isles. You can walk inside the Haghia Sophia, one of the most beautiful sacred spots on Earth, and marvel at some of the most gorgeous mosques in the world. You can visit the oldest inhabitations in the world, and the most contemporary assertion of regional (and global) ambitions. Turkey is much more than the cliché of “East meets West.” It is a microcosm of our one shared planet, with different groups of humanity living side by side, at times in tension, at times in peace.

One of the most memorable moments of the Gezi Park visit for me was that of the Whirling Dervish wearing the tear gas mask. It was a haunting image bringing together what has always been linked: the mystical, the political, the performative, and The Now. It does what every great cutting edge art should do: jolt us from our state of comfort from where we are, and point us towards where we should be. And this is the challenge for Turks and Turkey: can they somehow reconcile their dizzying and dazzling diversity into a mosaic of strength. Then again, using mosaics to depict scenes of beauty has been something people in this part of the world have done beautifully for some 2000 years.

It’s a great opportunity for Turkey to become an even more vibrant democracy.

The images in this blog are taken by the author, or are shared from social media sites of Turkish activists.