On Friday, The Atlantic featured a column with an intriguing headline:

Southern Evangelicals: Dwindling—and Taking the GOP Edge With Them

That’s the claim made by Robert Jones, president of the Public Religion Research Institute (PRRI). Jones showed results from a massive survey PRRI completed last year and compared them to Pew Research Center’s 2007 Religious Landscape survey. White evangelicals have dropped from 22 percent of Americans to just 18 percent.

Reading this, my spidey-sense started buzzing: that would be an 18 percent drop in just seven years! More than that, the numbers Jones were reporting didn’t match the 26 percent reported by the Landscape Survey. 18-22-26? The numbers didn’t make sense—at least not to me.

Re-reading the piece, I figured out part of the problem. The headline was a bait-and-switch. This wasn’t about all southern evangelicals but white southern evangelicals. And “white” meant excluding anyone who was Latino, too.

I ran the Pew data, moving anyone who was neither-white-nor-Latino out of the evangelical tradition. That reduced the evangelical percentage down to the 22% PRRI reported, but some of the state percentages were still much higher than Jones was reporting.

The problem, it turns out, was that PRRI departed from the Landscape Survey’s definition of “evangelical.” Pew followed the approach of many sociologists who group denominations into broad religious traditions. Protestants are usually placed into one of three traditions: evangelical Protestant, mainline Protestant, or black Protestant. PRRI used the same language of “religious tradition” and their survey had data on specific denominations, but they chose a different strategy.

Or, I should say that this is my best guess. PRRI has percentages reported on their 2013 data reported on their American Values Atlas (AVA) website. They don’t report how they measured religious tradition, and I couldn’t find it in their methodology report (which should include question wordings and other details). The AVA website offers more information, but this access requires a paid subscription to PRRI.

Jones reported Pew’s 2007 numbers, which gave me something to work with since Pew makes its data set public available for free. By trying different measurement strategies, I found a solution that resulted in the same figures Jones reported for both the country and key southern states.

PRRI collected denominational data, but it’s religious tradition categories apparently uses the person’s self-identification to divide white Protestants into “mainline” or “evangelical”. An evangelical is someone who says that they are a “born-again or evangelical Christian.” A mainline Protestant, according to PRRI, is anyone who doesn’t identify with this label.

There’s nothing inherently wrong with this. Pollsters often do this when they can’t ask a lot of detailed religion questions. Pew, in fact, does the same thing for its other polls. And like PRRI, when “white evangelical” is just white-not-Latino-self-identified-born-again, the percentage has dropped from 21 percent in 2007 to 18 or 19 percent.

But if I had detailed religion questions–and PRRI should–it’s not the choice that I would make. Self-identifications are more fluid than the choices people make about their religious community. The first surveys to bother to use questions on being “born-again” weren’t until the late 1970s. The addition of “evangelical” as an identification came even later, in part because being known as “born-again” was problematic. But where people go to church is far more durable.

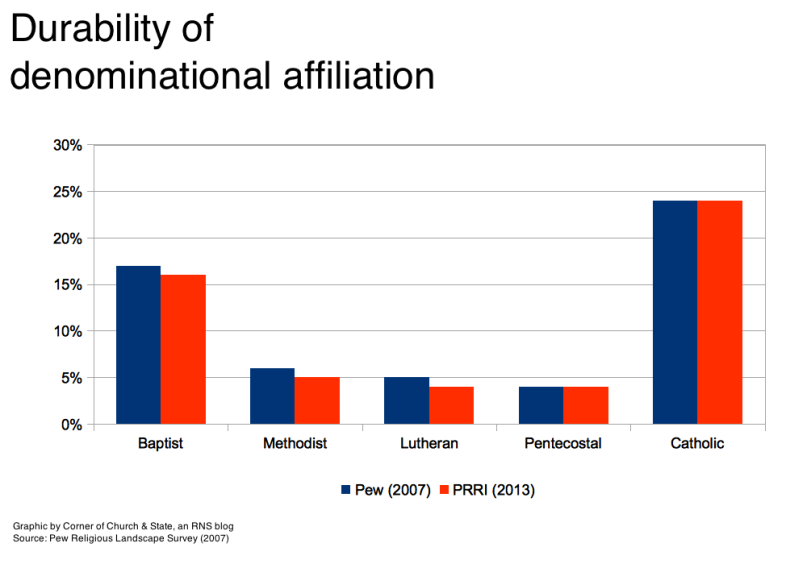

PRRI and Pew each report the percentage who are in “denominational families.” These are based solely on what type of church people attend or belong to. The five largest of these show virtually no change from 2007 to 2013. What changes are there are likely due to rounding or random chance.

Is it really possible that evangelicals have lost one-fifth of their members while there has been such very, very little change in denominations? The answer is “yes” only if you use a definition that isn’t based on where people go on Sunday.

Self-identification with the “born-again” label is generational and has changed over time. Like “feminist,” “conservative,” or “environmentalist,” self-identification means different things to different generations. It’s not surprising that Americans born after Time declared 1976 the “Year of the Evangelical” no longer identify with the same labels as their parents.

Take, for example, the following claim by Jones:

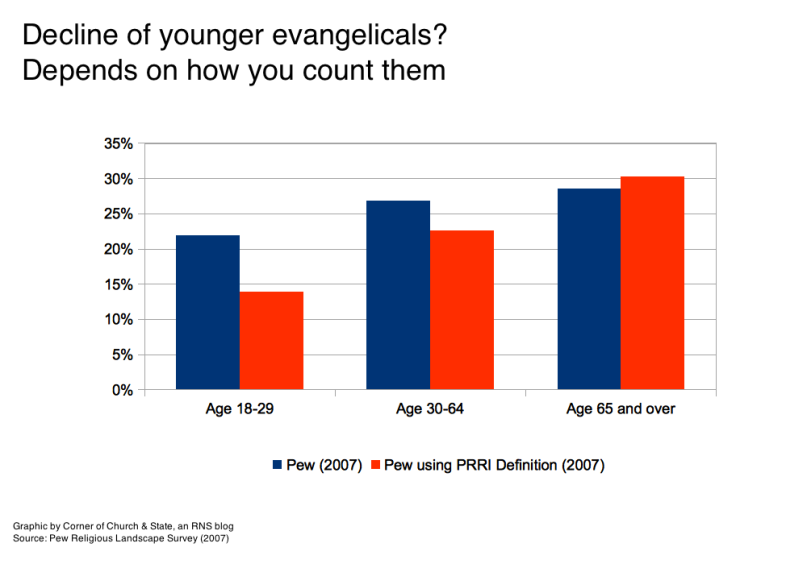

A look at generational differences demonstrates that this is only the beginnings of a major shift away from a robust white evangelical presence and influence in the country. While white evangelical Protestants constitute roughly three in 10 (29 percent) seniors (age 65 and older), they account for only one in 10 (10 percent) members of the Millennial generation (age 18-29).

We see the same pattern in the Pew data from 2007. Whites who were self-identified born-again Christians made up 30 percent of people 65 and older. Whites who were self-identified born-again Christians were just 14 percent of Americans 30 and younger. But that does not mean that there is a “major shift away from a robust white evangelical presence.” (ok, maybe the “white” part, but not the “evangelical” part).

These differences become much less stark when you a) don’t exclude people who go to an evangelical church just because they’re Latino or not white and b) use where they go to church, not their embrace of a “born-again” self-identification. The percentage of those 65 and older remained about the same (29% instead of 30%) because that is the generation for whom the “born-again” identification is meaningful. Younger evangelicals make up 22% of their age cohort, not just 14%, because they go to an evangelical church but they don’t self-identify that way.

Put another way: we see over 50% more evangelicals when we use their church, not their self-identification as “born-again”. They still go to Baptist, pentecostal, and non-denominational churches with conservative theology and social views. They don’t embrace an identification that they see as quaint. They see themselves as people with a “personal relationship with God,” or “just Christian” even as they go to the same church as gray-haired evangelicals who have always been “born-again Christians.”

They are also going to churches that are changing demographically, changes which PRRI ignores. True, there remains a black-white divide among Protestants but it is shrinking. The black churches founded due to racism in the 1800s created a religious tradition that remains largely separate from traditionally white evangelical and mainline churches. But there are people of color attending churches in the evangelical and mainline traditions, particularly Latinos and Asians. There is not a “Hispanic Protestant” tradition. And “Other Race Protestant” is a nonsensical category by anyone’s definition. There is not a “Hispanic Catholic” church. PRRI conflates religion with race to create categories that don’t make sense historically or sociologically.

They do, however, create headlines like those in The Atlantic. If one defines evangelicals as you would in the 1970s, then there has been a decline in white-only-born-again-Christians. But that’s not what’s happening. Evangelicalism–like the rest of America–is changing demographically. It’s less white, more Latino, and skeptical of labels than is previous decades. This change may not make great headlines, but it is a fascinating story nonetheless.

Don’t miss any more posts from the Corner of Church & State. Click the red subscribe button in the right hand column. Follow @TobinGrant on Twitter and on the Corner of Church & State Facebook page.