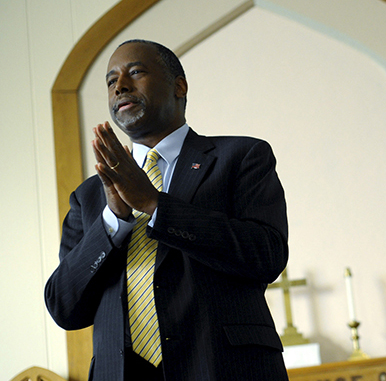

U.S. Republican presidential candidate Ben Carson speaks at South Bethel Church in Tipton, Iowa, on November 22, 2015. Photo courtesy of REUTERS/Mark Kauzlarich

*Editors: This photo may only be republished with RNS-CAMOSY-COLUMN, originally transmitted on Nov. 25, 2015.

(RNS) Ben Carson has a compelling story. He transcended profound poverty in Detroit to attend Yale, went on to the University of Michigan Medical School, and became head of pediatric neurosurgery at Johns Hopkins Hospital. On the basis of his outstanding career he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

His reputation as one of the best surgeons in the country played a significant role in Carson’s remarkable rise to the top of the GOP presidential field. Three weeks ago, Carson led Trump by 6 points nationwide and by double digits in Iowa.

In a country that prides itself on rejecting authority figures, physicians still manage to hold onto that role. We address them with the authoritative “doctor.” Our culture takes it for granted that physicians are the most sought-after spouses. They even walk around in special white coats received in a solemn medical school ceremony that strongly resembles an ordination.

Given that Carson was leading in the polls, the U.S. media began paying closer attention. But his performance under this pressure may have led supporters to rethink the authority they had assumed came with his position.

READ: Holiday 2015: A guide to gifts for everyone on your list, religious or not

In response to being pushed about his ridiculous belief that the Egypt’s pyramids were grain storage facilities, Carson doubled down. His own adviser admitted that Carson struggles to understand foreign policy. Almost totally tone deaf to how he is heard in our public discourse, Carson has compared Obamacare to slavery and Syrian refugees to dogs. Most recently, he was forced to walk back the claim that “thousands” of Muslims in New Jersey had celebrated the 9/11 attacks.

Predictably, Carson’s numbers have slipped dramatically. He is currently down 10 points relative to Trump nationwide, and he is now in third place in Iowa. Though it is possible for him to have a second act, many pundits believe that his candidacy is effectively over.

It must be said, however, that Carson is not the exception. He is the rule.

It turns out physicians — and especially surgeons — often have a very narrow set of knowledge and skills. Except for those who do primary care, it is probably best to think of most physicians as specialized organic plumbers. They are brought in, not to treat a person, but to treat a very specialized physical problem.

The courses of study that could give doctors a solid grounding for moral authority — philosophy, theology, history and ethics — have been traditionally eschewed by the medical and scientific communities as “soft.” In this view, the “hard sciences” are where true knowledge lies.

But then, remarkably, the same physicians who reject the study of the humanities as “soft,” proceed as if their study of organic plumbing gives them authority to make recommendations about matters of morality and value.

READ: On pornography, US Catholic bishops may find an unlikely ally (COMMENTARY)

Consider the following story told to me by my grandfather: He and a physician were discussing the evening whiskey he had been enjoying for many years. The physician basically said, “Hey, you’re 94, keep doing it.”

My grandmother was quite rightly very angry. This wasn’t medical advice. It was a personal judgment call based on values. It required thinking about the benefits of having the evening drink against the detriments of increased health problems — including the burden this would place on my grandmother.

For some reason, these kinds of moral judgments are simply assumed to be the province of the medical community.

Some physicians believe they have the moral authority to encourage abortion simply because a baby has Down syndrome. Or that dogs may be killed in the name of marginal medical progress. Some even believe they can get consent for complex medical experiments performed on desperately poor and uneducated people in the developing world.

READ: The ‘Splainer: Why should we give thanks?

These and dozens of other “medical” judgments not only involve questions of value and morality in which physicians have no authority, but their intuitions on these matters are often mistaken. For instance, the idea that physicians prefer quality of life to extended life was thought by The New York Times to “show others the way.”

But a 2011 study found that patients without the privileged perspective of an M.D. degree actually prefer length of life to quality of life.

“Often we think we know what is best for a patient, but this is often wrong,” said lead author Dr. Hans-Peter Brunner-La Rocca.

Charles C. Camosy is an associate professor of theological and social ethics at Fordham University, focusing on biomedical ethics. Photo courtesy of Charles C. Camosy

Indeed a meta-analysis of several studies shows that physicians rate the quality of their patients’ lives quite differently than the patients themselves. This makes it all the more disturbing that physicians feel entitled to take to the pages of The New York Times to argue for the kind paternalism where they “persuad(e) a patient to see things from your point of view.”

That physicians feel so entitled is our fault. We have vested them with a kind of moral authority they simply don’t deserve. Perhaps Dr. Ben Carson’s flagging candidacy can help teach our culture this much-needed lesson.

(Charles C. Camosy is an associate professor of theological and social ethics at Fordham University, focusing on biomedical ethics.)

YS/AMB END CAMOSY