In this job I receive plenty of heartwrenching emails from Mormons having faith crises. These are people for whom the LDS Church is no longer providing answers or comfort (or even basic acceptance, as seen in last month’s devastating policy changes on same-sex families).

In this job I receive plenty of heartwrenching emails from Mormons having faith crises. These are people for whom the LDS Church is no longer providing answers or comfort (or even basic acceptance, as seen in last month’s devastating policy changes on same-sex families).

They have often been through significant pain. They know what they are kicking against, but they’re not sure what is next in their journey. They have no map. I rarely know what to tell them except to express comfort and recommend fine books like Adam Miller’s Letters to a Young Mormon and The Crucible of Doubt by Terryl and Fiona Givens.

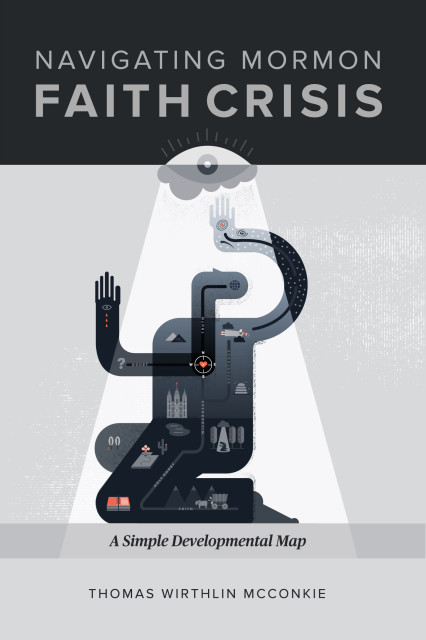

Now I have a third to offer, one of my favorite Mormon books this year. In Navigating Mormon Faith Crisis, Thomas Wirthlin McConkie, an expert in developmental psychology and the founder of MormonStages.com, says faith transitions actually follow a fairly reliable pattern.

Some of the pain of faith transitions is inevitable; after all, growth pangs accompany most kinds of change. That’s just a fact of life.

However, it can be comforting to know that what we’re going through isn’t unusual and certainly isn’t dangerous. Asking questions and having doubts doesn’t mean we are falling into apostasy — we’ve “simply driven off the edge of our current map.”

Or, as they say in Jaws, we’re gonna need a bigger boat.

In a later post, I’ll offer an interview with the author, but here I wanted to outline the basic premise of the book and the five stages of Mormon faith development. I’m kind of fascinated by them.

Diplomat: This foundational stage focuses on belonging and obeying the norms of the group. The blessings of this mindset are an emphasis on community and a deep sense of belonging. There’s a strong sense of tradition. The shadow sides of the Diplomat can be judgmentalism and blind obedience to authority. The letter of the law can win out over the spirit of the law. At this stage, if people begin to experience doubts, they often blame themselves and feel ashamed.

What’s crucial to remember here is that the “Diplomat anchors healthy growth at the later stages.” I was surprised and heartened by this. Some people claim that obedience is always bad, a hallmark of immaturity. Here, McConkie says that the study of development instead shows that “qualities that arise at the Diplomat stage are foundational and essential for flourishing in adult life.” They inform all the other stages.

(It occurs to me that when Mormons say that obedience is the first law of the gospel, it would be healthier for us to interpret first as meaning “an initial building block” rather than as “most important.”)

Expert: At this stage, individuals begin to search for other kinds of authority beyond the collective, thinking more abstractly and engaging with their own ideas. They will often put their trust in authorities whose opinions align with the ones they already hold.

Experts differ from Diplomats in that they want proof and strong reasoning in order to defend their ideas about religion. It’s not enough for them to be told “just follow the prophet and everything will be OK,” which the Diplomat is generally fine with. But a challenge of the Expert stage is that people can dig their heels in and marginalize any choices but their own. Experts are sometimes dogmatic and judgmental of people who disagree. And if they begin to experience a faith crisis, they can plunge into despair and perfectionism—if they can’t achieve perfect certainty, they may believe it’s their fault, so they double down and intensify their scripture study, fasting, etc., even as they feel less and less worthy.

Achiever: At this stage, people have become self-aware enough that they can be critical of their own thinking and at least a little more sensitive to the views of people who don’t agree. Not everything is black and white anymore; for every fact there is another potentially contrary fact. The Achiever attempts to weigh them all.

One of the great benefits of the Achiever is an emphasis on hard work and goal-setting – and we can do this while balancing our individual needs with the community’s, becoming “powerful team players.” But the Achiever is prone to burnout and identifying too strongly with what she does rather than who she is. (Boy, do I hear this.) There can be a competitive and even judgmental attitude to what other people have or have not accomplished.

Individualist: Most Mormon adults –- indeed, most people generally — probably fall in the Expert/Achiever range at this point in time. In the Individualist stage, which is a little rarer, people value “both/and” thinking rather than “either/or” thinking. The objective standards of success that are so important at the Achiever stage become less meaningful than what’s going on internally and the journey itself.

Individualists are very aware that what they “know” is conditioned by their culture, time period, and environment. They contribute by being out-of-the-box thinkers, willing to come up with new ways of doing things or even questioning why the heck they need to be done at all. Individualists tend to speak their truth with transparency, which makes some people uncomfortable. And because they value the way that personal experiences and backgrounds shape human beliefs, they seek mightily to bring unheard voices to the table.

More than people at any previous stage, Individualists have the capacity to be compassionate about the Church changing its mind about something. The Church, like any individual, is on a journey; and the Church, like the individual, is allowed to outgrow earlier views that have become too constricting. An Individualist’s faith won’t likely be shaken by anything that comes out of the process of continuing revelation.

On the other hand, this stage has drawbacks like any other. Individualists can become too inclusive of multiple perspectives and prone to relativism. They can also become impatient with power structures that are slow to develop and change.

Strategist: At this stage — even more rare than the last — the term “faith crisis” doesn’t exactly apply. A crisis is just an opportunity to change and grow, to be reborn with new eyes. At this stage we see that there’s no end to growth and become acutely aware of all we do not know. We follow Joseph Smith’s lead in drawing from every source of wisdom we can find as we search for new truths to integrate into Mormon belief.

The dangers of the Strategist stage are pride and a desire to see the people around us grow faster than they are likely able to do yet.

One caveat: In my interview with McConkie he emphasized that we never leave behind the earlier stages. We refine and express them throughout our lives. Furthermore, later stages are not necessarily healthier or more functional than earlier ones. It all depends on what we do with them.

I’ll post the interview tomorrow or next week, but in the meantime, consider checking out the book at MormonStages.com.