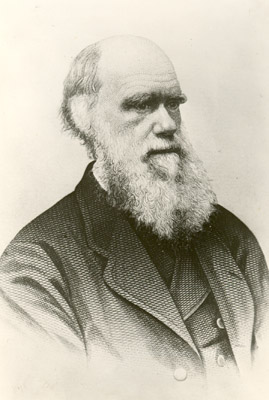

“Questioning Darwin,” a new, hourlong documentary airing on HBO throughout February, juxtaposes the story of the 19th-century British naturalist with looks into the lives of contemporary American Christians who believe the world was created in six days, as described in the Book of Genesis. Portrait of Charles Darwin (c. 1880) courtesy of HBO

(RNS) In 2005, a federal judge ruled that “intelligent design” — the idea that life is so complex it must have involved some sort of supernatural creator — isn’t science, but religion in disguise.

Science educators heralded the decision, and many thought it spelled the end of creationism in public schools.

They were wrong.

This week, as scientists, educators and others mark Feb. 12 as International Darwin Day — named for British naturalist Charles Darwin, who advanced the theory of evolution with his work on natural selection — the anti-evolution camp is as active as ever.

Opponents have managed to pass laws that permit the teaching of “alternatives” to evolution in Tennessee and Louisiana; Oklahoma and Iowa are considering similar bills. Another anti-evolution bill died on Feb. 4 in the South Dakota Senate.

But in the wake of the Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District ruling, their tactics have changed. And they have been successful enough in challenging evolution education the American Academy for the Advancement of Science is devoting three hours to the issue at their annual meeting in Washington, D.C. Feb. 11-15.

Anti-evolutionists have “come up with a policy that is vague enough to avoid court challenge so far, but specific enough that religiously conservative politicians will work to pass it,” said Nick Matzke, an evolutionary biologist who studied 60 anti-evolution bills and wrote about them in the journal Science.

Anti-evolutionists now speak of “Science Education Acts” and “academic freedom,” with no mention of a creator or designer.

They are also pairing origins science with other hot-button issues, such as climate change and human cloning.

READ: How romance king Nicholas Sparks fell in love with faith

“This tactic appears to be an attempt to circumvent earlier legal decisions suggesting that targeting evolution alone is … evidence of religious motivation and, thus, unconstitutional,” Matzke wrote in Science. “An additional motivation may be the dislike of climate change research by economic and religious conservatives.”

Matzke’s point is playing out in the presidential campaign. In December, NPR twice asked Sen. Ted Cruz, an evangelical Christian, whether he questioned evolution. Cruz linked his answer to climate change, which he doubts, and finally said of evolution: “Any good scientist questions all science. If you show me a scientist that stops questioning science, I’ll show you someone who isn’t a scientist.”

And Sen. Marco Rubio fumbled a reporter’s question on the age of the Earth, saying “I don’t think I’m qualified to answer a question like that. At the end of the day, I think there are multiple theories out there on how the universe was created and I think this is a country where people should have the opportunity to teach them all.”

Meanwhile, Americans are conflicted on the subject. In 2015, the Pew Research Center found 65 percent of Americans agreed with the statement “humans evolved over time.” But 31 percent reject evolution entirely, agreeing that humans have always existed in their present form.

Proponents of intelligent design say they have no agenda and are working to promote a scientific theory.

“Evolution is a constellation of lots of different questions and issues, and the peer-reviewed scientific literature is rife with disagreements about various parts of evolutionary theory,” John G. West, a senior fellow at the Discovery Institute, wrote in an email interview. “There certainly is a robust debate going on about the Darwinian mutation-selection mechanism and how much it can actually accomplish. If scientists can debate these questions in their science journals, why can’t students study these questions in their science classes?

“The question of whether nature displays evidence of design has been one of the great and continuing questions in the history of thought and the history of science,” West said. “Those who try to conflate this broader discussion of design with the narrower debate over creationism are either sadly ignorant of intellectual history or they are simply trying to avoid a discussion of the real issues.”

Barbara Forrest, a professor of philosophy at Southeastern Louisiana University, is having none of that. Forrest, whose testimony for the plaintiffs in Kitzmiller v. Dover traced the substitution of the term “intelligent design” for the word “creationism” in the textbook the Dover school board wanted to use, said proponents of intelligent design are now taking their agenda — and their fundraising efforts — overseas to Great Britain, Scotland and Brazil.

READ: West gathers digital arsenal against Islamic State — to what effect?

“That tells me they don’t see their fortunes getting better here in the U.S. so they are putting in more effort over there” where no First Amendment separation of church and state precludes the teaching of creationism in public schools, she said. “I think they are realizing their star here has gotten as high as it is going to go.”

Young-Earth creationists — people who believe God created the universe in six literal days about 6,000 years ago — also continue to protest evolution with anti-Darwin Day websites and events.

“We want to see critical thinking — not criticism as in shaking your finger at us for what we believe, but to look at things objectively and analyze the flaws of evolution,” said Cowboy Bob Sorensen, the founder of Question Evolution Day. “This is a resource for our side of the story on biblical science.”

There is a middle path. The Clergy Letter Project, an effort to show evolution and religion can coexist, has 14,000 Christian, Jewish and Buddhist signatories. They plan “Evolution Weekend” events on or near Darwin Day that include sermons, presentations and discussions on the compatibility of religion and science.

“It is important for parishioners to realize that some of the very loudest voices arguing evolution is an abomination and bad science are speaking loudly but narrowly for their own religion but not for other religions,” said Michael Zimmerman, founder of the Clergy Letter Project and a biologist at Evergreen State College in Olympia, Wash. “In fact, those voices are doing damage to religion in general as well as to science.”

(Kimberly Winston is a national correspondent for RNS)