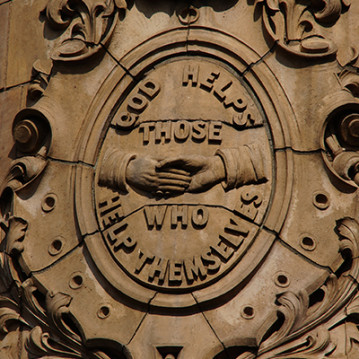

A new book exposes popular Christian cliches as unbiblical and damaging. – Image courtesy of Tim Ellis via Flickr (http://bit.ly/21Dvp8j)

“When God closes a door, God opens a window.”

The inspirational phrase is common among Christians and can be found on various China-made trinkets in your local religious bookstore. But when spoken to someone just handed a terminal diagnosis or languishing in poverty, the saccharine saying turns toxic. Sometimes the door closes and the windows are nailed shut.

In a era of spiritual sentimentality, Christian clichés like this can circulate among the faithful without scrutiny. We accept them because we want them to be true. But when we forage the Scriptures for them, they are nowhere to be found. And when we speak them at the wrong moment or to the wrong person, they can cause a tidal wave of emotional damage.

Several of these phrases are debunked in Adam Hamilton’s new book, Half Truths: God Helps Those Who Help Themselves and Other Things the Bible Doesn’t Say. As a pastor and Bible scholar, Hamilton helps us see the both the theological and emotional implications of our most common Christian clichés. Here are three that are particularly damaging:

1. Everything happens for a reason. A favorite phrase given to those who are suffering, this one can rub salt in an open wound. It’s as if we’re saying that even the most terrible events were “meant to be.” As Hamilton writes, “We seek to console, and others seek to console us, by saying that God has a particular purpose for bringing about (or at least allowing) situations in which people suffer.”

The scriptural reasoning behind this cliche is often derived from Romans 8:28: “And we know that in all things God works for the good of those who love him, who have been called according to his purpose.” The Apostle Paul does not say that everything happens for a reason. He does not say that everything–genocide, cancer, depression–is part of God’s will. Rather, Paul says that God will take even the most reasonless suffering and use it to accomplish some kind of good in the lives of those who love God. [tweetable]Tragedies happen in spite of God’s will, not because of it.[/tweetable]

-

God won’t give you more than you can handle. This cliche is another slap in the face to those experiencing tough times. A cursory reading of history or a few years of pastoral experience reveals heaps of stories about people who has more than they could handle. The first four words by themselves illustrate just how damaging this idea is: “God won’t give you.” As Hamilton says, “When we say those words, we are implying that whatever lousy things are happening in your life, God gave them to you.”

The scriptural reasoning behind this cliche is often derived from 1 Corinthians 10:13: “No temptation has overtaken you except what is common to mankind. And God is faithful: he will not let you be tempted beyond what you can bear. But when you are tempted, he will also provide a way out so that you can endure it.” The context for this verse is temptation, not trials or tragedies. As Hamilton writes, “It’s not that God won’t give you more than you can handle, but that God will help you handle all that you’ve been given.”

- Love the sinner, hate the sin. This cliche is one that has been used with increasing frequency in recent years because it is often invoked by conservative Christians in debates about homosexuality and gay marriage. Many who use this phrase don’t intend to harm others but wish to express love for another at some level.The scriptural reasoning behind this cliche is unclear. Jesus never asked us to “Love the sinner, hate the sin” and neither did any other Biblical writer. The closest phrases to this in Christian history, as Hamilton writes, are a letter from St. Augustine to a group of nuns (encouraging them to have “love for mankind and hatred of sins”). The clearest use of this phrase derives from Mahatma Gandhi in his 1929 autobiography: “Hate the sin and not the sinner.” But Gandhi’s full statement has a bit different flavor: “Hate the sin and not the sinner is a precept which, though easy enough to understand, is rarely practiced, and that is why the poison of hatred spreads in the world.”Gandhi rightly observed that it is difficult–perhaps impossible–to see someone else firstly as a “sinner” and to focus on “hating their sin” without developing some level of disdain for the person. Perhaps this is why Jesus did not ask us to love “sinners” but to love “neighbors” and “enemies.” As Hamilton writes:

I think Jesus knew that if he commanded his disciples to ‘love the sinner,’ they would begin looking at other people more as sinners than neighbors. And that, inevitably, would lead to judgment. If I love you more as a sinner than as my neighbor, then I am bound to focus more on your sin. I will start looking for all the things that are wrong with you. And perhaps, without intending it, I will being thinking about our relationship like this: “You are a sinner, but I graciously choose to love you anyway.” If that sounds a little puffed up, self-righteous, and even prideful to you, then you have perceived accurately.

Instead of loving others because you perceive them to be sinners, perhaps you should focus on loving them despite the fact that you are. If we all learn do this, perhaps the most damaging cliches in our collective vernacular will slowly be replaced by more gracious, life-giving–and yes–biblical words.